Related Research Articles

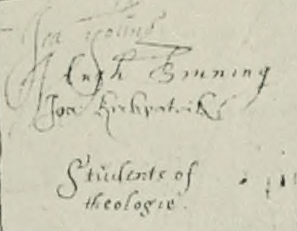

Hugh Binning (1627–1653) was a Scottish philosopher and theologian. He was born in Scotland during the reign of Charles I and was ordained in the (Presbyterian) Church of Scotland. He died in 1653, during the time of Oliver Cromwell and the Commonwealth of England.

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In September 1640, King Charles I issued writs summoning a parliament to convene on 3 November 1640. He intended it to pass financial bills, a step made necessary by the costs of the Bishops' Wars against Scotland. The Long Parliament received its name from the fact that, by Act of Parliament, it stipulated it could be dissolved only with agreement of the members; and those members did not agree to its dissolution until 16 March 1660, after the English Civil War and near the close of the Interregnum.

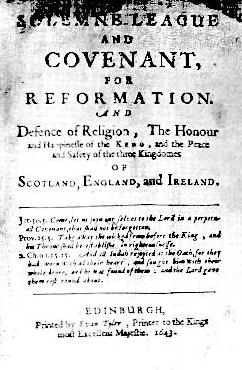

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians in 1643 during the First English Civil War, a theatre of conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. On 17 August 1643, the Church of Scotland accepted it and on 25 September 1643 so did the English Parliament and the Westminster Assembly.

John Campbell, 1st Earl of Loudoun was a Scottish politician and Covenanter.

George Gillespie was a Scottish theologian.

Archibald Johnston, Lord Wariston was a Scottish judge and statesman.

Robert Douglas (1594–1674) was the only minister of the Church of Scotland to be Moderator of the General Assembly five times.

Remonstrance may refer to:

David Dickson (1583–1663) was a Church of Scotland minister and theologian.

Patrick Gillespie (1617–1675) was a Scottish minister, strong Covenanter, and Principal of the University of Glasgow by the support of Oliver Cromwell.

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son Charles I over church organisation and doctrine, but expanded into political conflict over the limits of Royal authority.

Archibald Strachan was a Scottish soldier who fought in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, reaching the rank of colonel.

The Act of Classes was passed by the Parliament of Scotland on 23 January 1649. It was probably drafted by Lord Warriston, a leading member of the Kirk Party, who along with the Marquess of Argyll were leading proponents of its clauses. It banned Royalists and those who had supported the Engagement from holding public office including positions in the army. Against sizeable opposition the rescinding of the Act took effect on 13 August 1650.

James Guthrie, was a Scottish Presbyterian minister. Cromwell called him "the short man who would not bow." He was theologically and politically aligned with Archibald Johnston, whose illuminating 3 volume diaries were lost until 1896, and not fully published until 1940. He was exempted from the general pardon at the restoration of the monarchy, tried on 6 charges, and hanged in Edinburgh.

The Western Association was a Scottish military association to coordinate the military forces of the south western counties of Scotland during the War of the Three Kingdoms.

Captain William Govan (1623–1661). was a Scottish officer who fought for the Covenanters during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. He was awarded the honour of presenting Montrose's standard to the Scottish Parliament in 1650. He was accused of deserting the Scottish army later the same year and supporting the English New Model Army under the command of Oliver Cromwell, which was at that time invading Scotland. On 1 June 1661, the year after the restoration of the monarchy, and a few days after he was found guilty of treason, he was hanged as a traitor next to the Mercat Cross in Edinburgh and his head was put on a spike and displayed at West Port, Edinburgh.

Scotland under the Commonwealth is the history of the Kingdom of Scotland between the declaration that the kingdom was part of the Commonwealth of England in February 1652, and the Restoration of the monarchy with Scotland regaining its position as an independent kingdom, in June 1660.

Scottish religion in the seventeenth century includes all forms of religious organisation and belief in the Kingdom of Scotland in the seventeenth century. The 16th century Reformation created a Church of Scotland, popularly known as the kirk, predominantly Calvinist in doctrine and Presbyterian in structure, to which James VI added a layer of bishops in 1584.

John Livingstone was a Scottish minister. He was the son of William Livingstone, minister of Kilsyth, and afterwards of Lanark, said to be a descendant of the second son James, of the fourth Lord Livingston. His mother was Agnes, daughter of Alexander Livingston, portioner, Falkirk, brother of the Laird of Belstane.

John Row, born 1598, was the second son of John Row, minister of Carnock, and grandson of John Row, the Reformer. He educated at University of St Andrews graduating with an M.A. in 1617. He was elected schoolmaster of Kirkcaldy 2 November 1619, resigning before 25 November 1628. He was licensed by the Presbytery of Dalkeith 29 September 1631 and became tutor to George Hay, afterwards second Earl of Kinnoul, by whose father, the Lord Chancellor's recommendation, he was appointed master of the Grammar School of Perth in June 1632. He was ordained to Third Charge, Aberdeen, 14 December 1641 and appointed on 23rd November 1642 as lecturer on Hebrew in Marischal College. He was so actively engaged in support of the Covenanting party that on the approach of Montrose to Aberdeen in 1646 he was compelled to take refuge in Dunnottar Castle. Row was appointed by the General Assembly in 1647 to revise the new version of the Psalms from 90 to 120. He was a member of the Commission of Assembly in 1648, and of Commission for visiting the University of Aberdeen 31 July 1649. John Row joined the Independents and was admitted to a church of that persuasion in Edinburgh. He was promoted to Principalship of King's College in Aberdeen in September 1652. He resigned in 1661, and thereafter kept a school in Aberdeen. He died at the manse of Kinellar in October 1672 and was buried at Kinellar.

References

- Browne, James (1851). A history of the Highlands and of the Highland clans. Vol. 2. A. Fullarton. p. 67.

- Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas (1870). A Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Vol. 2. Blackie and son. p. 185.

- Mitchison, Rosalind (2002). A history of Scotland (3, illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 238. ISBN 0-415-27880-5.

- OED staff (2011) [2009]. "remonstrance, noun". Oxford English Dictionary (third online version ed.).

- The Reformed Presbyterian Church (2010). "Reformation History: The Engagement (1647)". The Reformed Presbyterian Church.

- Sime, William (1837). History of the covenanters in Scotland. Vol. 1. J. Johnstone. p. 134.

- Stevenson, David (1977). Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Scotland, 1644–1651 . Royal Historical Society. ISBN 9780901050359.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Sprott, George Washington (1890). "Gillespie, Patrick". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography . Vol. 21. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 361–363.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Sprott, George Washington (1890). "Gillespie, Patrick". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography . Vol. 21. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 361–363.