Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Confucianism developed from what was later called the Hundred Schools of Thought from the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE). Confucius considered himself a transmitter of cultural values inherited from the Xia (c. 2070–1600 BCE), Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE) and Western Zhou dynasties (c. 1046–771 BCE). Confucianism was suppressed during the Legalist and autocratic Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), but survived. During the Han dynasty, Confucian approaches edged out the "proto-Taoist" Huang–Lao as the official ideology, while the emperors mixed both with the realist techniques of Legalism.

Neo-Confucianism is a moral, ethical, and metaphysical Chinese philosophy influenced by Confucianism, which originated with Han Yu (768–824) and Li Ao (772–841) in the Tang dynasty, and became prominent during the Song and Ming dynasties under the formulations of Zhu Xi (1130–1200). After the Mongol conquest of China in the thirteenth century, Chinese scholars and officials restored and preserved neo-Confucianism as a way to safeguard the cultural heritage of China.

Li Qingzhao, also known as Yian Jushi was a Chinese poet and essayist during the Song dynasty. She is considered one of the greatest poets in Chinese history.

A paifang, also known as a pailou, is a traditional style of Chinese architectural arch or gateway structure.

Liu Rushi, also known as Yang Ai (楊愛), Liu Shi (柳是), Liu Yin (柳隱) and Yang Yin (楊隱),Yang Yinlian (楊影憐), Hedong Jun (河東君), was a Chinese Yiji, poet, calligrapher, and painter in the late Ming dynasty and early Qing dynasty.

Patriarchy in China refers to the history and prevalence of male dominance in Chinese society and culture, although patriarchy is not exclusive to Chinese culture and exists all over the world.

Traditional Chinese marriage is a ceremonial ritual within Chinese societies that involves not only a union between spouses but also a union between the two families of a man and a woman, sometimes established by pre-arrangement between families. Marriage and family are inextricably linked, which involves the interests of both families. Within Chinese culture, romantic love and monogamy were the norm for most citizens. Around the end of primitive society, traditional Chinese marriage rituals were formed, with deer skin betrothal in the Fuxi era, the appearance of the "meeting hall" during the Xia and Shang dynasties, and then in the Zhou dynasty, a complete set of marriage etiquette gradually formed. The richness of this series of rituals proves the importance the ancients attached to marriage. In addition to the unique nature of the "three letters and six rituals", monogamy, remarriage and divorce in traditional Chinese marriage culture are also distinctive.

The Biographies of Exemplary Women is a book compiled by the Han dynasty scholar Liu Xiang c. 18 BCE. It includes 125 biographical accounts of exemplary women in ancient China, taken from early Chinese histories including Chunqiu, Zuozhuan, and the Records of the Grand Historian. The book served as a standard Confucianist textbook for the moral education of women in traditional China for two millennia.

Wú Chéng or Wu Ch'eng, courtesy names Yòuqīng and Bóqīng, studio names Yīwúshānrén and Caolu Xiansheng, was a scholar, educator, and poet who lived in the late Song dynasty and Yuan dynasty. He was one of the most influential Neo-Confucian thinkers in those eras, and his influence continued to be prominent in the Ming and Qing periods.

Cheng Yi (1033–1107), also known by various other names and romanizations, was a Chinese classicist, essayist, philosopher, and politician of the Song Dynasty. He worked with his older brother Cheng Hao. Like his brother, he was a student of Zhou Dunyi, a friend of Shao Yong, and a nephew of Zhang Zai. The five of them along with Sima Guang are called the Six Great Masters by his follower Zhu Xi. He became a prominent figure in neo-Confucianism, and the philosophy of Cheng Yi, Cheng Hao and Zhu Xi is referred to as the Cheng–Zhu school or the Rationalistic School.

Qin Liangyu (1574–1648), courtesy name Zhensu, was a female general best known for defending the Ming dynasty from attacks by the Manchu-led Later Jin dynasty in the 17th century.

Han learning, or the Han school of classical philology, was an intellectual movement that reached its height in the middle of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) in China. The focus of the movement was to reject neo-Confucianism in order to return to a study of the original Confucian texts.

Pan Pingge, was a notable Chinese philosopher during the late-Ming and early-Qing period.

China's suicide rates were one of the highest in the world in the 1990s; however, by 2011, China had one of the lowest suicide rates in the world. According to the World Health Organization, the suicide rate in China was 9.7 per 100,000 as of 2016. As a comparison, the suicide rate in the U.S. in 2016 was 15.3. Generally speaking, China seems to have a lower suicide rate than neighboring Korea, Russia and Japan, and it is more common among women than men and more common in the Yangtze Basin than elsewhere.

Women in ancient and imperial China were restricted from participating in various realms of social life, through social stipulations that they remain indoors, whilst outside business should be conducted by men. The strict division of the sexes, apparent in the policy that "men plow, women weave", partitioned male and female histories as early as the Zhou dynasty, with the Rites of Zhou, even stipulating that women be educated specifically in "women's rites". Though limited by policies that prevented them from owning property, taking examinations, or holding office, their restriction to a distinctive women's world prompted the development of female-specific occupations, exclusive literary circles, whilst also investing certain women with certain types of political influence inaccessible to men. Women had greater freedom during the Tang dynasty, however, the status of women declined from the Song dynasty onward, which has been blamed on the rise of neo-Confucianism, and restrictions on women became more pronounced.

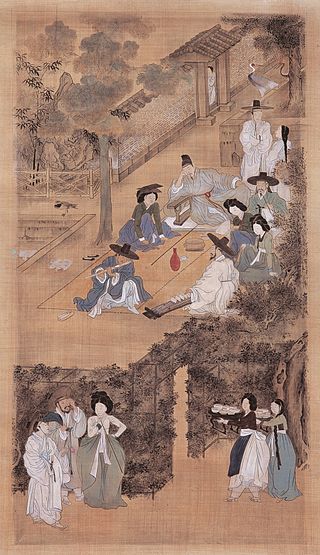

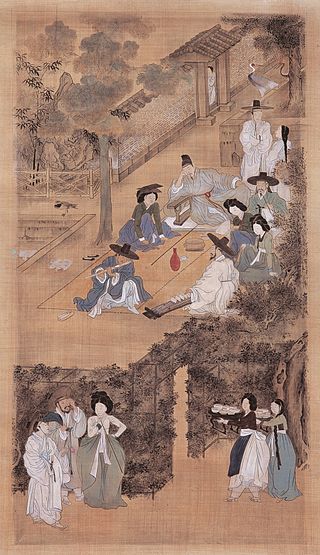

Society in the Joseon dynasty was built upon Neo-Confucianist ideals, namely the three fundamental principles and five moral disciplines. There were four classes: the yangban nobility, the "middle class" jungin, sangmin, or the commoners, and the cheonmin, the outcasts at the very bottom. Society was ruled by the yangban, who constituted 10% of the population and had several privileges. Slaves were of the lowest standing.

The Four Books for Women was a collection of material intended for use in the education of young Chinese women. In the late Ming and Qing dynasties, it was a standard text read by the daughters of aristocratic families. The four books had circulated separately and were combined by the publishing house Duowen Tang in 1624.

The Eight Beauties of Qinhuai, also called the Eight Beauties of Jinling, were eight famous Yiji or Geji during the Ming-Qing transition period who resided along the Qinhuai River in Nankin. As well as possessing great beauty, they were all skilled in literature, poetry, fine arts, dancing and music.

Concubinage in China traditionally resembled marriage in that concubines were recognized sexual partners of a man and were expected to bear children for him. Unofficial concubines were of lower status, and their children were considered illegitimate. The English term concubine is also used for what the Chinese refer to as pínfēi, or "consorts of emperors", an official position often carrying a very high rank. The practice of concubinage in China was outlawed when the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949.

Yeolnyeo, also called Yeolbu, is defined as 'virtuous woman' during the Joseon dynasty of Korea.