Related Research Articles

The earliest texts of William Shakespeare's works were published during the 16th and 17th centuries in quarto or folio format. Folios are large, tall volumes; quartos are smaller, roughly half the size. The publications of the latter are usually abbreviated to Q1, Q2, etc., where the letter stands for "quarto" and the number for the first, second, or third edition published.

Thomas Nabbes was an English dramatist.

Nicholas Culpeper was an English botanist, herbalist, physician and astrologer. His The English Physitian is a store of pharmaceutical and herbal knowledge, and Astrological Judgement of Diseases from the Decumbiture of the Sick (1655) one of the most detailed works on medical astrology in Early Modern Europe. Culpeper catalogued hundreds of outdoor medicinal herbs. He scolded some methods of contemporaries: "This not being pleasing, and less profitable to me, I consulted with my two brothers, Dr. Reason and Dr. Experience, and took a voyage to visit my mother Nature, by whose advice, together with the help of Dr. Diligence, I at last obtained my desire; and, being warned by Mr. Honesty, a stranger in our days, to publish it to the world, I have done it." Culpeper came from a line of notabilities, including Thomas Culpeper, lover of Queen Catherine Howard, also a distant relative, sentenced to death by her husband, Henry VIII.

Richard Brome ; was an English dramatist of the Caroline era.

John Colepeper, 1st Baron Culpeper of Thoresway was an English royalist landowner, military adviser and politician who, as Chancellor of the Exchequer (1642-43) and Master of the Rolls (1643) was an influential counsellor of King Charles I during the English Civil War, who rewarded him with a peerage and some landholdings in Virginia. During the Commonwealth he lived abroad in Europe, where he continued to act as a servant, advisor and supporter of King Charles II in exile. Having taken part in the Prince's escape into exile in 1646, Colepeper accompanied Charles in his triumphant return to England in May 1660, but died only two months later.

"To be, or not to be" is the opening phrase of a soliloquy given by Prince Hamlet in the so-called "nunnery scene" of William Shakespeare's play Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 1. In the speech, Hamlet contemplates death and suicide, bemoaning the pain and unfairness of life but acknowledging that the alternative might be worse. The opening line is one of the most widely known and quoted lines in modern English, and the soliloquy has been referenced in innumerable works of theatre, literature, and music.

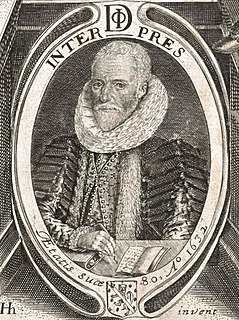

Philemon Holland was an English schoolmaster, physician and translator. He is known for the first English translations of several works by Livy, Pliny the Elder, and Plutarch, and also for translating William Camden's Britannia into English.

Charles Aleyn, a historical poet in the reign of Charles I, was of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge; became usher to the celebrated Thomas Farnaby, at his school, in Goldsmith's Rents, and afterwards tutor to Sir Edward Sherburne, himself a poet. He died about 1640.

Thomas May was an English poet, dramatist and historian of the Renaissance era.

John Benson was a London publisher of the middle seventeenth century, best remembered for a historically important publication of the Sonnets and miscellaneous poems of William Shakespeare in 1640.

William Aspley was a London publisher of the Elizabethan, Jacobean, and Caroline eras. He was a member of the publishing syndicates that issued the First Folio and Second Folio collections of Shakespeare's plays, in 1623 and 1632.

Richard Meighen was a London publisher of the Jacobean and Caroline eras. He is noted for his publications of plays of English Renaissance drama; he published the second Ben Jonson folio of 1640/1, and was a member of the syndicate that issued the Second Folio of Shakespeare's collected plays in 1632.

Richard Hawkins was a London publisher of the Jacobean and Caroline eras. He was a member of the syndicate that published the Second Folio collection of Shakespeare's plays in 1632. His bookshop was in Chancery Lane, near Sergeant's Inn.

Andrew Crooke and William Cooke were London publishers of the mid-17th-century. In partnership and individually, they issued significant texts of English Renaissance drama, most notably of the plays of James Shirley.

William Leake, father and son, were London publishers and booksellers of the late sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries. They were responsible for a range of texts in English Renaissance drama and poetry, including works by Shakespeare and Beaumont and Fletcher.

There have been two baronetcies created in the Baronetage of England for members of the Culpeper family of Kent and Sussex. Both are extinct.

Christopher Potter was an English academic and clergyman, Provost of The Queen's College, Oxford, controversialist and prominent supporter of William Laud.

Thomas Taylor (1576–1632) was an English cleric. A Calvinist, he held strong anti-Catholic views, and his career in the church had a long hiatus. He also attacked separatists, and wrote copiously, with the help of sympathetic patrons. He created a group of like-minded followers.

Sir William Allanson was an English merchant draper and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1640 to 1653.

References

- ↑ Horat. lib. i. epist. 1

- ↑ Harmes, Paul; Hart-Davies., Christina (2014). "The Life of Nicholas Culpeper and his Sussex records". Sussex Botanical Recording Society. Retrieved 11 September 2019.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ↑ iii. 320

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Grosart, Alexander Balloch (1885). "Attersoll, William (d.1640)". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography . 2. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Grosart, Alexander Balloch (1885). "Attersoll, William (d.1640)". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography . 2. London: Smith, Elder & Co.