Related Research Articles

John Whitgift was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1583 to his death. Noted for his hospitality, he was somewhat ostentatious in his habits, sometimes visiting Canterbury and other towns attended by a retinue of 800 horses. Whitgift's theological views were often controversial.

Edmund Grindal was Bishop of London, Archbishop of York, and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Elizabeth I. Though born far from the centres of political and religious power, he had risen rapidly in the church during the reign of Edward VI, culminating in his nomination as Bishop of London. However, the death of the King prevented his taking up the post, and along with other Marian exiles, he was a supporter of Calvinist Puritanism. Grindal sought refuge in continental Europe during the reign of Mary I. Upon Elizabeth's accession, Grindal returned and resumed his rise in the church, culminating in his appointment to the highest office.

Sir John Cheke was an English classical scholar and statesman. One of the foremost teachers of his age, and the first Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Cambridge, he played a great part in the revival of Greek learning in England. He was tutor to Prince Edward, the future King Edward VI, and also sometimes to Princess Elizabeth. Of strongly Reformist sympathy in religious affairs, his public career as provost of King's College, Cambridge, Member of Parliament and briefly as Secretary of State during King Edward's reign was brought to a close by the accession of Queen Mary in 1553. He went into voluntary exile abroad, at first under royal licence. He was captured and imprisoned in 1556, and recanted his faith to avoid death by burning. He died not long afterward, reportedly regretting his decision.

John Strype was an English clergyman, historian and biographer from London. He became a merchant when settling in Petticoat Lane. In his twenties, he became perpetual curate of Theydon Bois, Essex and later became curate of Leyton; this allowed him direct correspondence with several highly notable ecclesiastical figures of his time. He wrote extensively in his later years.

Sir Walter Mildmay was a statesman who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer to Queen Elizabeth I, and founded Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

Thomas Thirlby, was the first and only bishop of Westminster (1540–50), and afterwards successively bishop of Norwich (1550–54) and bishop of Ely (1554–59). While he acquiesced in the Henrician schism, with its rejection in principle of the Roman papacy, he remained otherwise loyal to the doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church during the English Reformation.

Matthew Hutton (1529–1606) was archbishop of York from 1595 to 1606.

John Piers (Peirse) was Archbishop of York between 1589 and 1594. Previous to that he had been Bishop of Rochester and Bishop of Salisbury.

Sir Henry Rolle (1589–1656), of Shapwick in Somerset, was Chief Justice of the King's Bench and served as MP for Callington, Cornwall, (1614–1623–4) and for Truro, Cornwall (1625–1629).

David Lindsay (1531–1613) was one of the twelve original ministers nominated to the "chief places in Scotland" in 1560. In 1589 as one of the recognised leaders of the Kirk and as chaplain of James VI of Scotland, Lindsay accompanied James to Norway to fetch home his bride. He was appointed bishop of Ross and a privy councillor in 1600. He was five times Moderator of the General Assembly: 1577, 1582, 1586, 1593 and 1597.

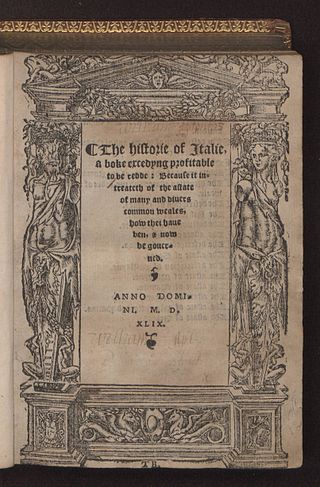

William Thomas, a Welshman from Llanigon, Brecknockshire, was a scholar of Italian and Italian history, politician and a clerk of the Privy Council under Edward VI. Thomas was executed for treason after the collapse of Wyatt's Rebellion under Mary I.

William Downham, otherwise known as William Downman, was Bishop of Chester early in the reign of Elizabeth I, having previously served as her domestic chaplain.

Alexander Neville (1544–1614) was an English scholar, known as a historian and translator and a Member of the House of Commons.

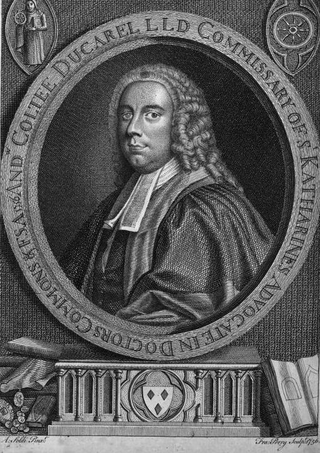

Andrew Coltée Ducarel was a French-English antiquary, librarian, and archivist. He was also a lawyer practising civil law, and a member of the College of Civilians.

William Grindal was an English scholar. A dear friend, pupil and protégé of Roger Ascham's at St John's College, Cambridge, he became tutor to Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen Elizabeth, and laid the foundations of her education in the Latin and Greek languages before dying prematurely of the plague in 1548.

Thomas Yale was the Chancellor, Vicar general and Official Principal of the Head of the Church of England : Matthew Parker, 1st Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, and Edmund Grindal, Bishop of London, during the Elizabethan Religious Settlement. He was also Dean of the Arches and Ambassador to his cousin, Queen Elizabeth Tudor, at the Court of High Commission.

Samuel Browne, of Arlesey, Bedfordshire, was Member of Parliament during the English Civil War and the First Commonwealth who supported the Parliamentary cause. However he refused to support the trial and execution of Charles I and, along with five of his colleagues, resigned his seat on the bench. At the Restoration of 1660 this was noted and he was made a judge of the Common Pleas.

Robert Hovenden D.D. (1544–1614) was an English academic administrator at the University of Oxford.

Anthony Hussey, Esquire, was an English merchant and lawyer who was President Judge of the High Court of Admiralty under Henry VIII, before becoming Principal Registrar to the Archbishops of Canterbury from early in the term of Archbishop Cranmer, through the restored Catholic primacy of Cardinal Pole, and into the first months of Archbishop Parker's incumbency, taking a formal part in the latter's consecration. The official registers of these leading figures of the English Reformation period were compiled by him. While sustaining this role, with that of Proctor of the Court of the Arches and other related ecclesiastical offices as a Notary public, he acted abroad as agent and factor for Nicholas Wotton.

Ford Palace was a residence of the Archbishops of Canterbury at Ford, about 6.6 miles (10.6 km) north-east of Canterbury and 2.6 miles (4.2 km) south-east of Herne Bay, in the parish of Hoath in the county of Kent in south-eastern England. The earliest structural evidence for the palace dates it to about 1300, and the earliest written references to it date to the 14th century. However, its site may have been in use for similar purposes since the Anglo-Saxon period, and it may have been the earliest such residence outside Canterbury.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Rigg, James McMullen (1888). "Drury, William (d.1589)". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography . Vol. 16. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 62, 63. endnotes:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Rigg, James McMullen (1888). "Drury, William (d.1589)". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography . Vol. 16. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 62, 63. endnotes: - Nichols's Progresses (James I), page 465

- Cullum's Hawsted, page 129

- Morant's Essex, ii. 311

- Cooper's Athenæ Cantabr. ii. 74.