Related Research Articles

Heinrich Müller was a high-ranking German Schutzstaffel (SS) and police official during the Nazi era. For most of World War II in Europe, he was the chief of the Gestapo, the secret state police of Nazi Germany. Müller was central in the planning and execution of the Holocaust and attended the January 1942 Wannsee Conference, which formalised plans for deportation and genocide of all Jews in German-occupied Europe—The "Final Solution to the Jewish Question". He was known as "Gestapo Müller" to distinguish him from another SS general named Heinrich Müller.

Adolf Hitler, chancellor and dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945, committed suicide via a gunshot to the head on 30 April 1945 in the Führerbunker in Berlin after it became clear that Germany would lose the Battle of Berlin, which led to the end of World War II in Europe. Eva Braun, his wife of one day, also committed suicide by cyanide poisoning. In accordance with Hitler's prior written and verbal instructions, that afternoon their remains were carried up the stairs and through the bunker's emergency exit to the Reich Chancellery garden, where they were doused in petrol and burned. The news of Hitler's death was announced on German radio the next day, 1 May.

Theodor Gilbert Morell was a German medical doctor known for acting as Adolf Hitler's personal physician. Morell was well known in Germany for his unconventional treatments. He assisted Hitler daily in virtually everything he did for several years and was beside Hitler until the last stages of the Battle of Berlin. Hitler granted Morell high awards, enabling the latter to become a multi-millionaire through business deals with the Nazi government, made possible by his status.

Gertraud "Traudl" Junge was a German editor who worked as Adolf Hitler's last private secretary from December 1942 to April 1945. After typing Hitler's will, she remained in the Berlin Führerbunker until his death. Following her arrest and imprisonment in June 1945, both the Soviet and the U.S. militaries interrogated her. Later, in post-war West Germany, she worked as a secretary. In her old age, she decided to publish her memoirs, claiming ignorance of the Nazi atrocities during the war, but blaming herself for missing opportunities to investigate reports about them. Her story, based partly on her book Until the Final Hour, formed a part of several dramatizations, in particular the 2004 German film Downfall about Hitler's final ten days.

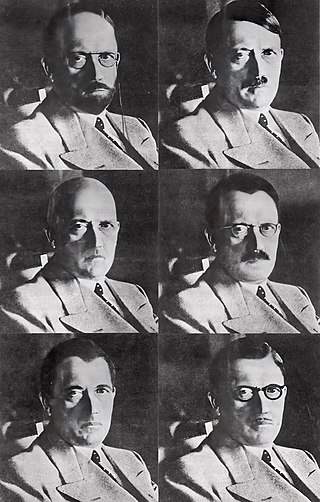

Although there is no evidence that Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler used look-alikes as political decoys during his life, some stories propagated as early as 1939 assert his death and replacement with an imposter. Following Hitler's suicide during the Battle of Berlin, the Soviet Union claimed to discover a number of bodies resembling the dictator, bolstering a disinformation campaign asserting Hitler's survival. Only the dictator's dental remains were confirmed, purportedly due to the cremation of his body.

Erich Kempka was a member of the SS in Nazi Germany who served as Adolf Hitler's primary chauffeur from 1936 to April 1945. He was present in the area of the Reich Chancellery on 30 April 1945, when Hitler shot himself in the Führerbunker. Kempka delivered the petrol to the garden behind the Reich Chancellery, where the remains of Hitler and Eva Braun were burned.

Gerda Christian, nicknamed "Dara", was one of Adolf Hitler's private secretaries before and during World War II.

Johanna Wolf was Adolf Hitler's chief secretary. Wolf joined Hitler's personal secretariat in the autumn of 1929 as a typist, at which time she also became a member of the Nazi Party. Wolf served as Hitler's chief secretary until the night of 21–22 April 1945, when she was ordered to fly out of Berlin to safety. She died on 5 June 1985.

The Reichssicherheitsdienst was an SS security force of Nazi Germany. Originally bodyguards for Adolf Hitler, it later provided men for the protection of other high-ranking leaders of the Nazi regime. The group, although similar in name, was completely separate from the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), which was the formal intelligence service for the SS, the Nazi Party and later Nazi Germany.

Günther August Wilhelm Schwägermann served in the Nazi government of German chancellor Adolf Hitler. From approximately late 1941, Schwägermann served as the adjutant for Joseph Goebbels. He reached the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer (captain). Schwägermann survived World War II and was held in American captivity from 25 June 1945 until 24 April 1947.

The Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit (KgU) was a German anti-communist resistance group based in West Berlin. It was founded in 1948 by Rainer Hildebrandt, Günther Birkenfeld, and Ernst Benda, and existed until 1959. Hildebrandt would later establish the Checkpoint Charlie Museum.

Hugo Johannes Blaschke was a German dental surgeon notable for being Adolf Hitler's personal dentist from 1933 to April 1945 and for being the chief dentist on the staff of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler.

The possibility that Adolf Hitler had only one testicle has been a fringe subject among historians and academics researching the Nazi leader. The rumour may be an urban myth, possibly originating from the contemporary British military song "Hitler Has Only Got One Ball".

Rudolf Weiß was a German officer appointed personal adjutant for the Army's Personnel Department Chief, a position he held until the end of World War II. Further, he was stationed in the Führerbunker in April 1945.

Jürgen Ohlsen was a German actor best remembered for portraying "Heini "Quex" Völker" in the 1933 Nazi propaganda film Hitlerjunge Quex.

Conspiracy theories about the death of Adolf Hitler, dictator of Germany from 1933 to 1945, contradict the accepted fact that he committed suicide in the Führerbunker on 30 April 1945. Stemming from a campaign of Soviet disinformation, most of these theories hold that Hitler and his wife, Eva Braun, survived and escaped from Berlin, with some asserting that he went to South America. In the post-war years, the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) investigated some of the reports, without lending them credence. The 2009 revelation that a skull in the Soviet archives long (dubiously) claimed to be Hitler's actually belonged to a woman has helped fuel conspiracy theories.

Anton Joachimsthaler is a German historian. He is particularly noted for his research on the early life of the German dictator Adolf Hitler, in his book Korrektur einer Biografie and his last days in the book Hitlers Ende, published in English as The Last Days of Hitler.

Richard Baier is a German former journalist and radio presenter.

The Death of Adolf Hitler: Unknown Documents from Soviet Archives is a 1968 book by Soviet journalist Lev Bezymenski, who served as an interpreter in the Battle of Berlin. The book gives details of the purported Soviet autopsies of Adolf Hitler, Eva Braun, Joseph and Magda Goebbels, their children, and General Hans Krebs. Each of these individuals are recorded as having died by cyanide poisoning; contrary to the Western conclusion that Hitler died by a suicide gunshot to the right temple.

Who Killed Hitler? is a 1947 American book edited by Herbert Moore and James W. Barrett, with an introduction by U.S. intelligence officer William F. Heimlich. The book contends that rather than commit suicide or escape Germany, Nazi leader Adolf Hitler was assassinated in an attempted coup d'état by Schutzstaffel (SS) leader Heinrich Himmler. The book criticizes claims of Hitler's survival and has also been criticized for bolstering them.

References

Citations

- ↑ Galle, Petra (2003) RIAS Berlin und Berliner Rundfunk 1945–1949. Münster: Lit Verlag. p.204. ISBN 3-825-86469-3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Staff (June 5, 1996) "William Heimlich Dies at 84" The Washington Post

- 1 2 3 4 Joachimsthaler, Anton (1996) The Last Days of Hitler: The Legends, the Evidence, the Truth. Translated by Helmut Bögler. London: Arms and Armour. pp. 25, 28–29 & 284,n.21 ISBN 1-85409-380-0

- ↑ Musmanno, Michael A. (1950). Ten Days to Die. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. pp. 233–234.

- ↑ Moore, Herbert; Barrett, James W., eds. (1947). Who Killed Hitler?. W. F. Heimlich (foreword). New York: The Booktab Press. p. iii.

- ↑ Daly-Groves 2019, p. 15.

- ↑ Daly-Groves 2019, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Evans 2020, p. 254.

Bibliography

- Daly-Groves, Luke (2019). Hitler's Death: The Case Against Conspiracy. Oxford, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-4728-3454-6.

- Evans, Richard (2020). The Hitler Conspiracies. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190083052.

Further reading

- Domentat, Tamara and Heimlich, Christina (2000) Heimlich im Kalten Krieg. Die Geschichte von Christina Ohlsen und Bill Heimlich ("Secretly in the Cold War: The Story of Christina Ohlsen and Bill Heimlich") Berlin: Aufbau Verlag, ISBN 3-351-02507-6