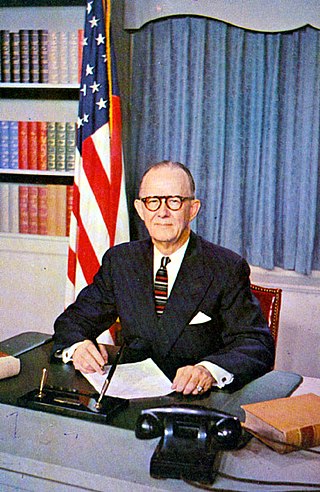

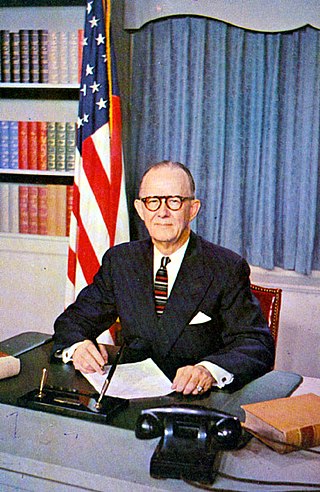

Orval Eugene Faubus was an American politician who served as the 36th Governor of Arkansas from 1955 to 1967, as a member of the Democratic Party. In 1957, he refused to comply with a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education, and ordered the Arkansas National Guard to prevent black students from attending Little Rock Central High School. This event became known as the Little Rock Crisis. He was elected to six two-year terms as governor.

Little Rock Central High School (LRCH) is an accredited comprehensive public high school in Little Rock, Arkansas, United States. The school was the site of the Little Rock Crisis in 1957 after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation by race in public schools was unconstitutional three years earlier. This was during the period of heightened activism in the civil rights movement.

Adolphine Fletcher Terry (1882–1976) was an American political and social activist in the state of Arkansas. Terry leveraged her position within the Little Rock community to affect change in causes related to social justice, women's rights, racial equality, housing, and education. Fletcher is most remembered for her role on the Women's Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC) that was primarily responsible for reopening the Little Rock, Arkansas, public school system and bringing to a close the school district closing in 1958, following the Crisis at Little Rock Central High. In its "Millennium Poll" in 2000, the Arkansas Historical Association named Terry one of the state's 15 most significant figures in state history.

Thomas Dale Alford Sr. was an American ophthalmologist and politician from the U.S. state of Arkansas who served as a conservative Democrat in the United States House of Representatives from Little Rock from 1959 to 1963.

Daisy Bates was an American civil rights activist, publisher, journalist, and lecturer who played a leading role in the Little Rock Integration Crisis of 1957.

James Douglas Johnson, known as "Justice Jim" Johnson, was an Arkansas legislator and jurist known for outspoken support of racial segregation during the mid-20th century. He served as an associate justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court from 1959 to 1966, and in the Arkansas Senate from 1951 to 1957. Johnson unsuccessfully sought several elected positions, including Governor of Arkansas in 1956 and 1966, and the United States Senate in 1968. A segregationist, Johnson was frequently compared to George Wallace of Alabama. He joined the Republican Party in 1983.

Lawrence Brooks Hays was an American lawyer and politician who served eight terms as a Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives from the State of Arkansas from 1943 to 1959. He was also a president of the Southern Baptist Convention.

Massive resistance was a strategy declared by U.S. senator Harry F. Byrd Sr. of Virginia and his son Harry Jr.'s brother-in-law, James M. Thomson, who represented Alexandria in the Virginia General Assembly, to get the state's white politicians to pass laws and policies to prevent public school desegregation, particularly after Brown v. Board of Education.

Ronald Norwood Davies was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of North Dakota. He is best known for his role in the Little Rock Integration Crisis in the fall of 1957. Davies ordered the desegregation of the previously all-white Little Rock Central High.

Harry Scott Ashmore was an American journalist who won a Pulitzer Prize for his editorials in 1957 on the school integration conflict in Little Rock, Arkansas.

The 1966 Arkansas gubernatorial election was held on November 8, 1966. Winthrop Rockefeller was elected governor of Arkansas, becoming the first Republican to be elected to the office since Reconstruction in 1872.

The Little Rock Nine were a group of nine African American students enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Their enrollment was followed by the Little Rock Crisis, in which the students were initially prevented from entering the racially segregated school by Orval Faubus, the Governor of Arkansas. They then attended after the intervention of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Mary Brown Williams Ledbetter, better known as Brownie Ledbetter, was a political activist, social justice crusader and lobbyist who was involved in the civil rights, feminist, labor and environmental movements in Arkansas, United States and abroad.

Vivion Mercer Lenon Brewer was an American desegregationist, most notable for being a founding member of the Women's Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC) in 1958 during the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas.

In the United States, school integration is the process of ending race-based segregation within American public and private schools. Racial segregation in schools existed throughout most of American history and remains an issue in contemporary education. During the Civil Rights Movement school integration became a priority, but since then de facto segregation has again become prevalent.

The 1958 Arkansas gubernatorial election was held on November 4, 1958.

White America, Inc., was an organization founded in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, in February 1955. The organization was created following the desegregation of schools in Arkansas, to attempt to prevent "any attempts by Negroes to enter white schools" in the state. The group joined two other militant white supremacist organizations in September 1955 to attempt to intimidate the local school board of Hoxie to reverse its decision to integrate its schools.

Sara Alderman Murphy was a civil rights activist living in Little Rock, Arkansas during the school integration attempts in the 1950s. She was born in Wartrace, Tennessee. She earned her BA in Social Studies and English from Vanderbilt University in 1945 and a MS in Journalism from Columbia University. She was a faculty member of Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana and then at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. Sara Murphy joined the Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC) after the attempt to integrate Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957. She was on the WEC board in 1962 and 1963. In 1963 she founded a branch of the Panel of American Women (PAW) in Little Rock and became vice-president of the national PAW from 1971 to 1974. From 1972-1975 she was the vice-chairperson of the Governor’s Commission on the Status of Women. In 1982 she founded Peace Links, an organization to ease international tensions through discussion and personal interactions. She was the president of Arkansas’ Peace Links from 1982-1984. She wrote Breaking the Silence, a book about the role of the WEC in the Little Rock integration crisis.

African Americans have played an essential role in the history of Arkansas, but their role has often been marginalized as they confronted a society and polity controlled by white supremacists. During the slavery era to 1865, they were considered property and were subjected to the harsh conditions of forced labor. After the Civil War and the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Reconstuction Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, African Americans gained their freedom and the right to vote. However, the rise of Jim Crow laws in the 1890s and early 1900s led to a period of segregation and discrimination that lasted into the 1960s. Most were farmers, working their own property or poor sharecroppers on white-owned land, or very poor day laborers. By World War I, there was steady emigration from farms to nearby cities such as Little Rock and Memphis, as well as to St. Louis and Chicago.

The Ministers' Manifesto refers to a series of manifestos written and endorsed by religious leaders in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, during the 1950s. The first manifesto was published in 1957 and was followed by another the following year. The manifestos were published during the civil rights movement amidst a national process of school integration that had begun several years earlier. Many white conservative politicians in the Southern United States embraced a policy of massive resistance to maintain school segregation. However, the 80 clergy members that signed the manifesto, which was published in Atlanta's newspapers on November 3, 1957, offered several key tenets that they said should guide any debate on school integration, including a commitment to keeping public schools open, communication between both white and African American leaders, and obedience to the law. In October 1958, following the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation Temple bombing in Atlanta, 311 clergy members signed another manifesto that reiterated the points made in the previous manifesto and called on the governor of Georgia to create a citizens' commission to help with the eventual school integration process in Atlanta. In August 1961, the city initiated the integration of its public schools.