A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that are associated with specific signs and symptoms. A disease may be caused by external factors such as pathogens or by internal dysfunctions. For example, internal dysfunctions of the immune system can produce a variety of different diseases, including various forms of immunodeficiency, hypersensitivity, allergies, and autoimmune disorders.

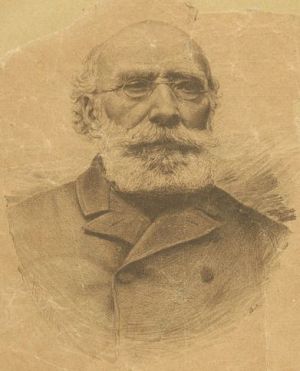

Louis Pasteur was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the last of which was named after him. His research in chemistry led to remarkable breakthroughs in the understanding of the causes and preventions of diseases, which laid down the foundations of hygiene, public health and much of modern medicine. Pasteur's works are credited with saving millions of lives through the developments of vaccines for rabies and anthrax. He is regarded as one of the founders of modern bacteriology and has been honored as the "father of bacteriology" and the "father of microbiology".

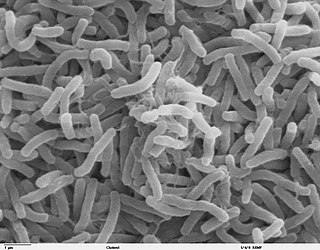

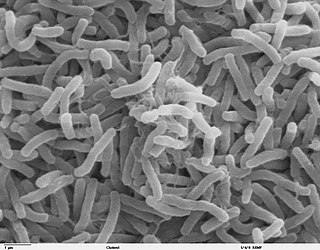

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic size, which may exist in its single-celled form or as a colony of cells.

A human pathogen is a pathogen that causes disease in humans.

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable disease, is an illness resulting from an infection.

A biological hazard, or biohazard, is a biological substance that poses a threat to the health of living organisms, primarily humans. This could include a sample of a microorganism, virus or toxin that can adversely affect human health. A biohazard could also be a substance harmful to other living beings.

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade humans, other animals, and other living hosts. Their growth and reproduction within their hosts can cause disease. "Germ" refers to not just a bacterium but to any type of microorganism, such as protists or fungi, or other pathogens that can cause disease, such as viruses, prions, or viroids. Diseases caused by pathogens are called infectious diseases. Even when a pathogen is the principal cause of a disease, environmental and hereditary factors often influence the severity of the disease, and whether a potential host individual becomes infected when exposed to the pathogen. Pathogens are disease-carrying agents that can pass from one individual to another, both in humans and animals. Infectious diseases are caused by biological agents such as pathogenic microorganisms as well as parasites.

Brucellosis is a zoonosis caused by ingestion of unpasteurized milk from infected animals, or close contact with their secretions. It is also known as undulant fever, Malta fever, and Mediterranean fever.

Melioidosis is an infectious disease caused by a gram-negative bacterium called Burkholderia pseudomallei. Most people exposed to B. pseudomallei experience no symptoms; however, those who do experience symptoms have signs and symptoms that range from mild, such as fever and skin changes, to severe with pneumonia, abscesses, and septic shock that could cause death. Approximately 10% of people with melioidosis develop symptoms that last longer than two months, termed "chronic melioidosis".

Glanders is a contagious zoonotic infectious disease that occurs primarily in horses, mules, and donkeys. It can be contracted by other animals, such as dogs, cats, pigs, goats, and humans. It is caused by infection with the bacterium Burkholderia mallei.

Postpartum infections, also known as childbed fever and puerperal fever, are any bacterial infections of the female reproductive tract following childbirth or miscarriage. Signs and symptoms usually include a fever greater than 38.0 °C (100.4 °F), chills, lower abdominal pain, and possibly bad-smelling vaginal discharge. It usually occurs after the first 24 hours and within the first ten days following delivery.

A contagious disease is an infectious disease that is readily spread by transmission of a pathogen through contact with an infected person.

Rat-bite fever (RBF) is an acute, febrile human illness caused by bacteria transmitted by rodents, in most cases, which is passed from rodent to human by the rodent's urine or mucous secretions. Alternative names for rat-bite fever include streptobacillary fever, streptobacillosis, spirillary fever, bogger, and epidemic arthritic erythema. It is a rare disease spread by infected rodents and caused by two specific types of bacteria:

- Streptobacillus moniliformis, the only reported bacteria that causes RBF in North America

- Spirillum minus, common in Asia. Most cases occur in Japan, but specific strains of the disease are present in the United States, Europe, Australia, and Africa.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) refers to pneumonia contracted by a person outside of the healthcare system. In contrast, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is seen in patients who have recently visited a hospital or who live in long-term care facilities. CAP is common, affecting people of all ages, and its symptoms occur as a result of oxygen-absorbing areas of the lung (alveoli) filling with fluid. This inhibits lung function, causing dyspnea, fever, chest pains and cough.

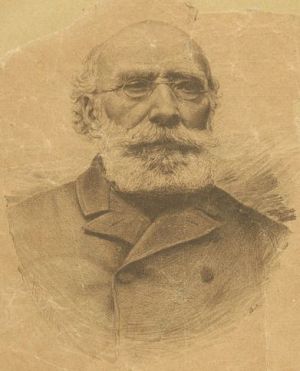

Pierre Jacques Antoine Béchamp was a French scientist now best known for breakthroughs in applied organic chemistry and for a bitter rivalry with Louis Pasteur.

Günther Enderlein was a German zoologist, entomologist, microbiologist, researcher, physician for 60 years, and later a manufacturer of pharmaceutical products. Enderlein received international renown for his insect research, and in Germany became famous due to his concept of the pleomorphism of microorganisms and his hypotheses about the origins of cancer, based on the work of other scientists. His hypotheses about pleomorphism and cancer have now been disproved by science and have only some historical importance today. Some of his concepts, however, are still popular in alternative medicine. A blood test is named after him: dark field microscopy according to Enderlein.

Pathogenic bacteria are bacteria that can cause disease. This article focuses on the bacteria that are pathogenic to humans. Most species of bacteria are harmless and are often beneficial but others can cause infectious diseases. The number of these pathogenic species in humans is estimated to be fewer than a hundred. By contrast, several thousand species are part of the gut flora present in the digestive tract.

In biology, a pathogen, in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ.

Germ theory denialism is the pseudoscientific belief that germs do not cause infectious disease, and that the germ theory of disease is wrong. It usually involves arguing that Louis Pasteur's model of infectious disease was wrong, and that Antoine Béchamp's was right. In fact, its origins are rooted in Béchamp's empirically disproven theory of pleomorphism. Another obsolete variation is known as terrain theory and postulates that the state of the internal environment determines if germs cause disease rather than germs being the sole cause of it.

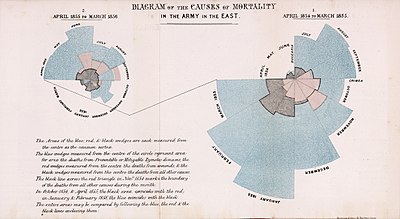

In the mid to late nineteenth century, scientific patterns emerged which contradicted the widely held miasma theory of disease. These findings led medical science to what we now know as the germ theory of disease. The germ theory of disease proposes that invisible microorganisms are the cause of particular illnesses in both humans and animals. Prior to medicine becoming hard science, there were many philosophical theories about how disease originated and was transmitted. Though there were a few early thinkers that described the possibility of microorganisms, it was not until the mid to late nineteenth century when several noteworthy figures made discoveries which would provide more efficient practices and tools to prevent and treat illness. The mid-19th century figures set the foundation for change, while the late-19th century figures solidified the theory.