Related Research Articles

Pierre Brissaud was a French Art Deco illustrator, painter, and engraver whose father was Docteur Edouard Brissaud, a student of Docteur Charcot. He was born in Paris and trained at the École des Beaux-Arts and Atelier Fernand Cormon in Montmartre, Paris. His fellow Cormon students were his brother Jacques, André-Édouard Marty, Charles Martin, Georges Lepape. Students at the workshop drew, painted and designed wallpaper, furniture and posters. Earlier, Toulouse-Lautrec, van Gogh, and Henri Matisse had studied and worked there. His older brother Jacques Brissaud was a portrait and genre painter and his uncle Maurice Boutet de Monvel illustrated the fables of La Fontaine, songbooks for children and a life of Joan of Arc. A first cousin was the celebrated artist and celebrity portrait painter Bernard Boutet de Monvel.

Édouard François André was a French horticulturalist, landscape designer, as well as a leading landscape architect of the late 19th century, famous for designing city parks and public spaces in Lithuania, Monte Carlo and Montevideo.

Aimé Nicolas Morot was a French painter and sculptor in the Academic Art style.

Maison Devambez is the name of a fine printer's firm in Paris. It operated under that name from 1873, when a printing business established by the royal engraver Hippolyte Brasseux in 1826 was acquired by Édouard Devambez. At first the firm specialized in heraldic engraving, engraved letterheads and invitations. Devambez clients included the House of Orléans, the House of Bonaparte and the Élysée Palace. Devambez widened the scope of the business to include advertising and publicity, artists’ prints, luxurious limited edition books, and an important art gallery. The House became recognized as one of the foremost fine engravers in Paris, winning numerous medals and honours. With the artist Édouard Chimot as Editor after the First World War, a series of limited edition art books, employing leading French artists, illustrators and affichistes, reached a high point under the imprimatur A l'Enseigne du Masque d'Or – the Sign of the Golden Mask and with PAN in collaboration with Paul Poiret. Édouard's son, André Devambez, became a famous painter and illustrator after receiving the Prix de Rome.

Camille Hilaire was a French painter and weaver from Metz. He attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris during World War II and was also tutored by André Lhote.

Bernard Boutet de Monvel was a French painter, sculptor, engraver, fashion illustrator and interior decorator. Although first known for his etchings, he earned notability for his paintings, especially his geometric paintings from the 1900s and his Moroccan paintings made during World War I. In both Europe and the United States, where he often traveled, he also became known as a portrait painter for high society clients.

Louis Monziès was a French painter and etcher. He was the curator of the three Museums of Le Mans for 10 years until his death.

Paul Biva was a French painter. His paintings, both Realist, Naturalist in effect, principally represented intricate landscape paintings or elaborate flower settings, much as the work of his older brother, the artist Henri Biva (1848–1929). Paul Biva was a distinguished member of National Horticultural Society of France from 1898 until his untimely death two years later.

Auguste Brouet (1872–1941) was a French etcher and book illustrator.

André Victor Édouard Devambez was a French painter and illustrator, notably of children's books.

Adolphe van Bever was a 19th–20th-century French bibliographer and erudite.

Louis Perceau was a 20th-century French polygraph. He used several pseudonyms including Helpey bibliographe poitevin, Dr. Ludovico Hernandez, Alexandre de Vérineau, Un vieux journaliste, Radeville et Deschamps, marquis Boniface de Richequeue, sometimes jointly with Fernand Fleuret.

Louis-Pierre Bougie was a Canadian painter and printmaker specialized in engraving and etching. He developed his knowledge of intaglio techniques at Atelier Lacourière-Frélaut in Paris, where he worked for fifteen years, and through travel and study in France, Portugal, Poland, Ireland, Finland, and New York. His work is regularly shown in Canadian, American, and European galleries, and is represented in major public and private collections, notably in Québec and New York. Bougie was considered Québec's foremost engraver for the depth and consistency of his work. He died from pneumonia.

Alan Marshall is a British historian who works in France. He specialised in the history of printing, in particular that of phototypesetting.

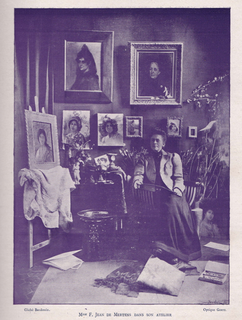

Fernande Hortense Cécile de Mertens was a Belgian-French painter.

Valère Bernard was a Provençal painter, engraver, novelist and poet, writing in the Occitan language. He left an important body of graphic work, and his works continued to be published after his death.

Maurice Busset was a French painter and woodcut engraver. During World War I he was an airman and an official war artist, and a significant number of his works relate to aviation during the war. His other main subject was his native Auvergne.

Antoine Schneck is a French visual-art photographer born in 1963 in Suresnes, France.

André Villeboeuf was a French illustrator, painter, watercolorist, printmaker, writer and stage designer.

Maurice Paul Jean Asselin was a French painter, watercolourist, printmaker, lithographer, engraver and illustrator, associated with the School of Paris. He is best known for still lifes and nudes. Other recurring themes in his work are motherhood, and the landscapes and seascapes of Brittany. He also worked as a book illustrator, particularly in the 1920s. His personal style was characterised by subdued colours, sensitive brushwork and a strong sense of composition and design.