Related Research Articles

The United Mine Workers of America is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the United States and Canada. Although its main focus has always been on workers and their rights, the UMW of today also advocates for better roads, schools, and universal health care. By 2014, coal mining had largely shifted to open pit mines in Wyoming, and there were only 60,000 active coal miners. The UMW was left with 35,000 members, of whom 20,000 were coal miners, chiefly in underground mines in Kentucky and West Virginia. However it was responsible for pensions and medical benefits for 40,000 retired miners, and for 50,000 spouses and dependents.

The Ludlow Massacre was a mass killing perpetrated by anti-striker militia during the Colorado Coalfield War. Soldiers from the Colorado National Guard and private guards employed by Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I) attacked a tent colony of roughly 1,200 striking coal miners and their families in Ludlow, Colorado, on April 20, 1914. Approximately 21 people, including miners' wives and children, were killed. John D. Rockefeller Jr., a part-owner of CF&I who had recently appeared before a United States congressional hearing on the strikes, was widely blamed for having orchestrated the massacre.

The One Big Union is an idea originating in the late 19th and early 20th centuries amongst trade unionists to unite the interests of workers and offer solutions to all labour problems.

The Coal strike of 1902 was a strike by the United Mine Workers of America in the anthracite coalfields of eastern Pennsylvania. Miners struck for higher wages, shorter workdays, and the recognition of their union. The strike threatened to shut down the winter fuel supply to major American cities. At that time, residences were typically heated with anthracite or "hard" coal, which produces higher heat value and less smoke than "soft" or bituminous coal.

In the Lattimer massacre, at least 19 unarmed striking immigrant anthracite miners were killed violently at the Lattimer mine near Hazleton, Pennsylvania, United States, on September 10, 1897. The miners, mostly of Polish, Slovak, Lithuanian and German ethnicity, were shot and killed by a Luzerne County sheriff's posse. Scores more workers were wounded. The massacre was a turning point in the history of the United Mine Workers (UMW).

The Harlan County War, or Bloody Harlan, was a series of coal industry skirmishes, executions, bombings and strikes that took place in Harlan County, Kentucky, during the 1930s. The incidents involved coal miners and union organizers on one side and coal firms and law enforcement officials on the other. The Harlan County coal miners campaigned and fought to organize their workplaces and better their wages and working conditions. It was a nearly decade-long conflict, lasting from 1931 to 1939. Before its conclusion, an unknown number of miners, deputies and bosses would be killed, state and federal troops would occupy the county more than half a dozen times, two acclaimed folk singers would emerge, union membership would oscillate wildly and workers in the nation's most anti-labor coal county would ultimately be represented by a union.

The Battle of Blair Mountain was the largest labor uprising in United States history and is the largest armed uprising since the American Civil War. The conflict occurred in Logan County, West Virginia, as part of the Coal Wars, a series of early-20th-century labor disputes in Appalachia.

The Paint Creek–Cabin Creek Strike, or the Paint Creek Mine War, was a confrontation between striking coal miners and coal operators in Kanawha County, West Virginia, centered on the area enclosed by two streams, Paint Creek and Cabin Creek.

The West Virginia coal wars (1912–1921), also known as the mine wars, arose out of a dispute between coal companies and miners.

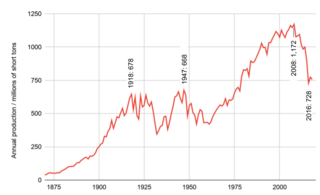

The history of coal mining in the United States starts with the first commercial use in 1701, within the Manakin-Sabot area of Richmond, Virginia. Coal was the dominant power source in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and although in rapid decline it remains a significant source of energy in 2023.

The Battle of Virden, also known as the Virden Mine Riot and Virden Massacre, was a labor union conflict and a racial conflict in central Illinois that occurred on October 12, 1898. After a United Mine Workers of America local struck a mine in Virden, Illinois, the Chicago-Virden Coal Company hired armed detectives or security guards to accompany African-American strikebreakers to start production again. An armed conflict broke out when the train carrying these men arrived at Virden. Strikers were also armed: a total of five detective/security guards and eight striking mine workers were killed, with five guards and more than thirty miners wounded. In addition, at least one black strikebreaker on the train was wounded. The engineer was shot in the arm. This was one of several fatal conflicts in the area at the turn of the century that reflected both labor union tension and racial violence. Virden, at this point, became a sundown town, and most black miners were expelled from Macoupin County.

The Pana riot, or Pana massacre, was a coal mining labor conflict and also a racial conflict that occurred on April 10, 1899, in Pana, Illinois, and resulted in the deaths of seven people. It was one of many similar labor conflicts in the coal mining regions of Illinois that occurred in 1898 and 1899.

The Illinois coal wars, also known as the Illinois mine wars and several other names, were a series of labor disputes between 1898 and 1900 in central and southern Illinois.

The Coal Wars were a series of armed labor conflicts in the United States, roughly between 1890 and 1930. Although they occurred mainly in the East, particularly in Appalachia, there was a significant amount of violence in Colorado after the turn of the century.

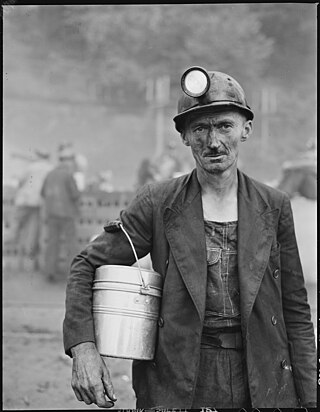

People have worked as coal miners for centuries, but they became increasingly important during the Industrial revolution when coal was burnt on a large scale to fuel stationary and locomotive engines and heat buildings. Owing to coal's strategic role as a primary fuel, coal miners have figured strongly in labor and political movements since that time.

The Federal Coal Commission was an agency of the Federal government of the United States of America, enacted by the U.S. Congress in September 1922 and headed by former U.S. Vice President Thomas R. Marshall.

Patton was an unincorporated community in Walker County, in the U.S. state of Alabama. "Patton" and "Patton Junction" are often treated as different names for a single community.

The Carterville Mine Riot was part of the turn-of-the-century Illinois coal wars in the United States. The national United Mine Workers of America coal strike of 1897 was officially settled for Illinois District 12 in January 1898, with the vast majority of operators accepting the union terms: thirty-six to forty cents per ton, an 8-hour day, and union recognition. However, several mine owners in Carterville, Virden, and Pana, refused or abrogated. They attempted to run with African-American strikebreakers from Alabama and Tennessee. At the same time, lynching and racial exclusion were increasingly practiced by local white mining communities. Racial segregation was enforced within and among UMWA-organized coal mines.

The 1959 United Mine Workers strike was a labor action by union miners in Eastern Kentucky. Originally over a pay increase, it grew into a conflict between union and non-union mines that resulted in three deaths. It was the first instance of labor violence in the area since the Harlan County War and was the prelude to the Roving Picket Movement.

In 1915, coal miners affiliated with the United Mine Workers (UMW) labor union at the Wheelbarrow Mine in Johnson County, Arkansas, went on strike against the mine's operators, the Pennsylvania Mining Company (PMC). The strike ended in 1917 after the PMC declared bankruptcy and a new company, the Fernwood Mining Company, was established to operate the mine and quickly agreed to recognize the UMW.

References

- ↑ "1920's".

- 1 2 Feldman, Glenn (June 1994). "Labour Repression in the American South: Corporation, State, and Race in Alabama's Coal Fields, 1917-1921" . The Historical Journal. 37 (2): 349. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00016502. JSTOR 2640206. S2CID 161955836 . Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ "Strike Called in Alabama to Determine Whether Coal Operators Are Stronger Than Government". United Mine Workers Journal. XXXI (18): 13. September 15, 1920. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- 1 2 Tindall 1995, p. 337.

- ↑ Foner 1991, p. 228.

- 1 2 Letwin, Daniel (1998). The Challenge of Interracial Unionism. Chapel Hill, N.C: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 186. ISBN 9780807823774 . Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ↑ "President Lewis Urges President Wilson to Take Legal Action to Compel Observance of Principle of Collective Bargaining by Alabama Operators". United Mine Workers Journal. XXXI (21): 3. November 1, 1920. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Woodrum 2007, p. 13.

- ↑ Kelly 2001, p. 174.

- ↑ Davis, Colin John; Brown, Edwin L. (1999). It is union and liberty : Alabama coal miners and the UMW. University of Alabama Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 9780817309992 . Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Rothermel, J. Fisher (September 17, 1920). "Strikers Pitch Camp". The Birmingham News. Vol. XXXIII, no. 188. Birmingham, Alabama. p. 2. Retrieved 15 December 2021– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Lewis 2009, p. 60.

- ↑ Kelly 2001, p. 187.

- ↑ "Thomas Erby Kilby". Alabama Department of Archives and History. February 7, 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2021.[ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ Kelly 2001, p. 178.

- ↑ Foner 1991, p. 229.

- ↑ Chenery, William L. (April 9, 1921). Kellogg, Paul U. (ed.). "The Alabama Coal Settlement". The Survey. New York: Survey Associates Inc. XLVI: 52. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ Woodrum 2007, p. 48.

- ↑ Lewis 2009, p. 61.

- 1 2 Kelly 2001, p. 196.