The Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) is a 13.8-mile (22.2 km) rapid transit system in the northeastern New Jersey cities of Newark, Harrison, Jersey City, and Hoboken, as well as Lower and Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is operated as a wholly owned subsidiary of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. PATH trains run around the clock year-round; four routes serving 13 stations operate during the daytime on weekdays, while two routes operate during weekends, late nights, and holidays. It crosses the Hudson River through cast iron tunnels that rest on a bed of silt on the river bottom. It operates as a deep-level subway in Manhattan and the Jersey City/Hoboken riverfront; from Grove Street in Jersey City to Newark, trains run in open cuts, at grade level, and on elevated track. In 2023, the system saw 55,109,100 rides, or about 205,600 per weekday in the third quarter of 2024, making it the fifth-busiest rapid transit system in the United States.

New Jersey Transit Corporation, branded as NJ Transit or NJTransit and often shortened to NJT, is a state-owned public transportation system that serves the U.S. state of New Jersey and portions of the states of New York and Pennsylvania. It operates buses, light rail, and commuter rail services throughout the state, connecting to major commercial and employment centers both within the state and in its two adjacent major cities, New York City and Philadelphia. In 2023, the system had a ridership of 209,259,800.

Secaucus Junction is an intermodal transit hub served by New Jersey Transit and Metro-North Railroad in Secaucus, New Jersey. It is one of the busiest railway stations in North America.

The Pascack Valley Line is a commuter rail line operated by the Hoboken Division of New Jersey Transit, in the U.S. states of New Jersey and New York. The line runs north from Hoboken Terminal, through Hudson and Bergen counties in New Jersey, and into Rockland County, New York, terminating at Spring Valley. Service within New York is operated under contract with Metro-North Railroad. The line is named for the Pascack Valley region that it passes through in northern Bergen County. The line parallels the Pascack Brook for some distance. The line is colored purple on system maps, and its symbol is a pine tree.

Hoboken Terminal is a commuter-oriented intermodal passenger station in Hoboken, Hudson County, New Jersey. One of the New York metropolitan area's major transportation hubs, it is served by eight NJ Transit (NJT) commuter rail lines, an NJ Transit event shuttle to Meadowlands Sports Complex, one Metro-North Railroad line, various NJT buses and private bus lines, the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail, the Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) rapid transit system, and NY Waterway-operated ferries.

A buffer stop, bumper, bumping post, bumper block or stopblock (US), is a device to prevent railway vehicles from going past the end of a physical section of track.

Atlantic Terminal is the westernmost commuter rail terminal on the Long Island Rail Roa's (LIRR) Atlantic Branch, located at Flatbush Avenue and Atlantic Avenue in Downtown Brooklyn, New York City. It is the primary terminal for the West Hempstead Branch, and a peak-hour terminal for some trains on the Hempstead Branch, Far Rockaway Branch, Port Jefferson Branch,Ronkonkoma Branch, and the Babylon Branch; most other service is provided by frequent shuttles to Jamaica station. The terminal is located in the City Terminal Zone, the LIRR's Zone 1, and thus part of the CityTicket program.

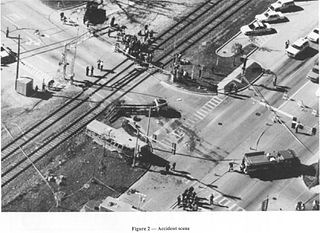

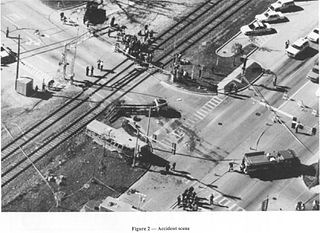

The 1995 Fox River Grove bus–train collision was a grade crossing collision that killed seven students riding aboard a school bus in Fox River Grove, Illinois, on the morning of October 25, 1995. The school bus, driven by a substitute driver, was stopped at a traffic light with the rearmost portion extending onto a portion of the railroad tracks when it was struck by a Metra Union Pacific Northwest Line train, train 624 en route to Chicago.

Kingsland is a railroad station on New Jersey Transit's Main Line. It is located under Ridge Road (Route 17) between New York and Valley Brook Avenues in Lyndhurst, New Jersey, and is one of two stations in Lyndhurst. The station is not staffed, and passengers use ticket vending machines (TVMs) located at street level to purchase tickets. The station is not handicapped-accessible. Originally part of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad's Boonton Branch, the current Kingsland station was built in 1918. The station is currently planned to be closed.

The Comet V railcar is the fifth generation of the Comet railcar series. Produced by the manufacturer Alstom, the Comet V is a rather different car compared to previous models in the series. The Comet V has been in use by New York metropolitan area commuter rail operators New Jersey Transit and Metro-North since April 2002.

On May 28, 2008, shortly before 6 p.m., two westbound MBTA trains collided on the Green Line D branch between Woodland and Waban stations, behind 56 Dorset Road in Newton, Massachusetts. An investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) originally found the cause of the accident to be due to the operator texting while driving, but the NTSB later found that the operator of the rear train, Terrese Edmonds, had not been using her cell phone at the time of the crash, but rather went into an episode of micro-sleep, causing her to lose awareness of her surroundings and miss potential hazards up ahead. The collision killed Edmonds, and numerous others were injured. Fourteen passengers were taken to area hospitals; one was airlifted. This crash, along with another similar accident a year later, led the NTSB to set higher standards and regulations regarding the use of cell phones while operating a train.

The 2008 Chatsworth train collision occurred at 4:22:23 p.m. PDT on September 12, 2008, when a Union Pacific Railroad freight train and a Metrolink commuter rail passenger train collided head-on in the Chatsworth neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, United States.

On February 16, 1996, a MARC commuter train collided with Amtrak's Capitol Limited passenger train in Silver Spring, Maryland, United States, killing three crew and eight passengers on the MARC train; a further eleven passengers on the same train and fifteen passengers and crew on the Capitol Limited were injured. Total damage was estimated at $7.5 million.

The Fairfield/Bridgeport train crash occurred on May 17, 2013, when a Metro-North Railroad passenger train derailed between the Fairfield Metro and Bridgeport stations in Fairfield, Connecticut, in the United States. The derailed train fouled the adjacent line and a train heading in the opposite direction then collided with it. There were at least 650 injured among the approximately 2500 people on board each of the two trains. Metro-North reported damages at $18.5 million.

On the morning of December 1, 2013, a Metro-North Railroad Hudson Line passenger train derailed near the Spuyten Duyvil station in the New York City borough of the Bronx. Four of the 115 passengers were killed and another 61 injured; the accident caused $9 million worth of damage. It was the deadliest train accident within New York City since a 1991 subway derailment in Manhattan, and the first accident in Metro-North's history to result in passenger fatalities. The additional $60 million in legal claims paid out as of 2020 have also made it the costliest accident in Metro-North's history.

On the evening of February 3, 2015, a commuter train on Metro-North Railroad's Harlem Line struck a passenger car at a grade crossing on Commerce Street near Valhalla, New York, United States. Six people were killed and 15 others injured, seven severely. It is the deadliest crash in Metro-North's history, and was at the time the deadliest rail accident in the United States since the June 2009 Washington Metro train collision, which killed nine passengers and injured 80.

On April 3, 2016, Amtrak train 89, the southbound Palmetto, struck a backhoe while travelling through Chester, Pennsylvania, killing two track workers and derailing the locomotive, as well as damaging the first two cars.

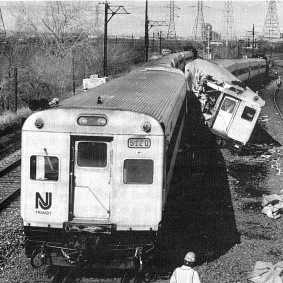

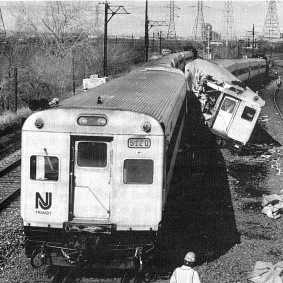

On February 9, 1996, two NJ Transit commuter trains collided at Bergen Junction in Secaucus, New Jersey, United States. This accident occurred during the morning rush hour just south of the current Secaucus Junction station. It is NJ Transit's deadliest accident to date and the first in which passengers and crew died. Three people were killed and 162 injured.