The Pan Africanist Congress of Azania is a South African national liberation Pan-Africanist movement that is now a political party. It was founded by an Africanist group, led by Robert Sobukwe, that broke away from the African National Congress (ANC) in 1959, as the PAC objected to the ANC's "the land belongs to all who live in it both white and black" and also rejected a multiracialist worldview, instead advocating a South Africa based on African nationalism.

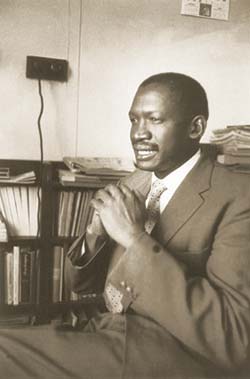

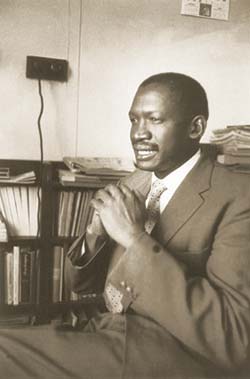

Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe OMSG was a South African anti-apartheid revolutionary and founding member of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), serving as the first president of the organization.

The Azanian People's Organisation (AZAPO) is a South African liberation movement and political party. The organisation's two student wings are the Azanian Students' Movement (AZASM) for high school learners and the other being for university level students called the Azanian Students' Convention (AZASCO), its women's wing is Imbeleko Women's Organisation, simply known as IMBELEKO. Its inspiration is drawn from the Black Consciousness Movement inspired philosophy of Black Consciousness developed by Steve Biko, Harry Nengwekhulu, Abram Onkgopotse Tiro, Vuyelwa Mashalaba and others, as well as Marxist Scientific Socialism.

The Basutoland Congress Party is a pan-Africanist and left-wing political party in Lesotho.

One Settler, One Bullet was a rallying cry and slogan originated by the Azanian People's Liberation Army (APLA), the armed wing of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), during the struggle of the 1980s against apartheid in South Africa. The slogan parodied the African National Congress's slogan 'One Man, One Vote', which eventually became 'One Person, One Vote'. It is not to be confused with the controversial protest song "Dubul' ibhunu".

John Nyathi "Poks" Pokela was a South African political activist and Chairman of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC).

Vusumzi L. Make was a South African civil rights activist and lawyer. He and the American poet Maya Angelou met in 1961, lived together in Cairo, Egypt, before parting ways in 1962. He was a professor at the University of Liberia in Monrovia, Liberia, from 1968 to 1974.

Johnson Phillip Mlambo was a South African politician from Johannesburg.

Potlako Kitchener Leballo was an Africanist who led the Pan Africanist Congress until 1979. Leballo was co-founder of the Basutoland African Congress in 1952, a World War II veteran and primary school headmaster.

Zephania Lekoame Mothopeng was a South African political activist and member of the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC).

This article covers the history of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania, once a South African liberation movement and now a minor political party.

Letlapa Mphahlele is a member of the National Assembly of South Africa who represents the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania. He is from Manaleng in the Northern Cape Province.

The Operational Medal for Southern Africa was instituted by the President of the Republic of South Africa in 1998. It was awarded to veteran cadres of Umkhonto we Sizwe and the Azanian People's Liberation Army for operational service outside South Africa during the "struggle".

The South Africa Service Medal was instituted by the President of the Republic of South Africa in 1998. It was awarded to veteran cadres of Umkhonto we Sizwe and the Azanian People's Liberation Army for operational service inside South Africa during the "struggle".

The Gold Star for Bravery, post-nominal letters GSB, was instituted by the President of the Republic of South Africa in April 1996. It was awarded to veteran cadres of the Azanian People's Liberation Army, the military wing of the Pan Africanist Congress, who had distinguished themselves during the "struggle" by performing acts of exceptional bravery in great danger.

The Lesotho Liberation Army (LLA) was a guerrilla movement in Lesotho, formed in the mid-1970s and connected to the anti-Apartheid Azanian People's Liberation Army (APLA). It was the armed wing of the Basutoland Congress Party (BCP), a pan-Africanist and left-wing political party founded in 1952, which opposed the regime of Prime Minister Leabua Jonathan.

Clarence Mlami Makwetu was a South African anti-apartheid activist, politician, and leader of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) during the historic 1994 elections.

On 8 October 1993, Mzwandile Mfeya, Sandiso Yose, twins Samora and Sadat Mpendulo and Thando Mtembu were shot dead in a South African Defence Force (SADF) raid on an alleged base of the Azanian People's Liberation Army (APLA), the Pan Africanist Congress' military wing, at the Mpendulo family home in the Northcrest suburb of Mthatha. The house belonged to a PAC member Sigqibo Mpendulo, the father of Samora and Sadat. According to PAC and police sources in the Transkei, the five victims were killed in their beds. The raid was authorised by President F. W. de Klerk.

Sabelo Victor Phama [born Sabelo Gqwetha] was an Anti-Aparthaid Activist, Military Commander of Azanian People's Liberation Army APLA and Secretary of Defense in the Pan African Congress PAC. He is best known for organising a campaign of politically and racially motivated attacks on white civilians that took place in 1993; resulting in 24 deaths and 122 serious injuries.

Kenny Thabo Motsamai is a South African anti-apartheid activist, convicted murderer and politician. A member of the Economic Freedom Fighters party, he has been a permanent delegate to the National Council of Provinces from Gauteng since May 2019. Motsamai is a former military commander of the Azanian People's Liberation Army, the military wing of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania during apartheid. He was imprisoned for nearly three decades for killing a white traffic officer during a bank robbery in 1989.