Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of production and the economy at large. Developed in French labor unions during the late 19th century, syndicalist movements were most predominant amongst the socialist movement during the interwar period which preceded the outbreak of World War II.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with industrial unionism, as it is a general union, subdivided between the various industries which employ its members. The philosophy and tactics of the IWW are described as "revolutionary industrial unionism", with ties to socialist, syndicalist, and anarchist labor movements.

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in broader society. The end goal of syndicalism is to abolish the wage system, regarding it as wage slavery. Anarcho-syndicalist theory generally focuses on the labour movement. Reflecting the anarchist philosophy from which it draws its primary inspiration, anarcho-syndicalism is centred on the idea that power corrupts and that any hierarchy that cannot be ethically justified must be dismantled.

Industrial unionism is a trade union organising method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in bargaining and in strike situations.

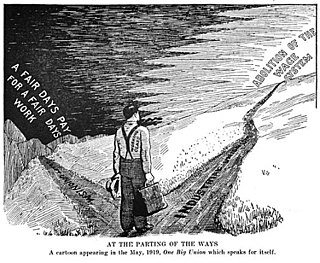

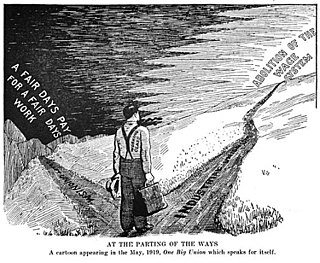

The One Big Union was an idea in the late 19th and early 20th centuries amongst trade unionists to unite the interests of workers and offer solutions to all labour problems.

The International Workers' Association – Asociación Internacional de los Trabajadores (IWA–AIT) is an international federation of anarcho-syndicalist labor unions and initiatives.

Anarchism in Africa refers both to purported anarchic political organisation of some traditional African societies and to modern anarchist movements in Africa.

Anarchism in South Africa dates to the 1880s, and played a major role in the labour and socialist movements from the turn of the twentieth century through to the 1920s. The early South African anarchist movement was strongly syndicalist. The ascendance of Marxism–Leninism following the Russian Revolution, along with state repression, resulted in most of the movement going over to the Comintern line, with the remainder consigned to irrelevance. There were slight traces of anarchist or revolutionary syndicalist influence in some of the independent left-wing groups which resisted the apartheid government from the 1970s onward, but anarchism and revolutionary syndicalism as a distinct movement only began re-emerging in South Africa in the early 1990s. It remains a minority current in South African politics.

Trade unions in South Africa has a history dating back to the 1880s. From the beginning unions could be viewed as a reflection of the racial disunity of the country, with the earliest unions being predominantly for white workers. Through the turbulent years of 1948–1991 trade unions played an important part in developing political and economic resistance, and eventually were one of the driving forces in realising the transition to an inclusive democratic government.

James Thomson "JT" Bain was a socialist and syndicalist in colonial South Africa.

Anarchism in Ireland has its roots in the stateless organisation of the túatha in Gaelic Ireland. It first began to emerge from the libertarian socialist tendencies within the Irish republican movement, with anarchist individuals and organisations sprouting out of the resurgent socialist movement during the 1880s, particularly gaining prominence during the time of the Dublin Socialist League.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is a union of wage workers which was formed in Chicago in 1905 by militant unionists and their supporters due to anger over the conservatism, philosophy, and craft-based structure of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Throughout the early part of the 20th century, the philosophy and tactics of the IWW were frequently in direct conflict with those of the AFL concerning the best ways to organize workers, and how to best improve the society in which they toiled. The AFL had one guiding principle—"pure and simple trade unionism", often summarized with the slogan "a fair day's pay for a fair day's work." The IWW embraced two guiding principles, fighting like the AFL for better wages, hours, and conditions, but also promoting an eventual, permanent solution to the problems of strikes, injunctions, bull pens, and union scabbing.

The One Big Union (OBU) was a Canadian syndicalist trade union active primarily in the western part of the country. It was initiated formally in Calgary on June 4, 1919, but lost most of its members by 1922. It finally merged into the Canadian Labour Congress in 1956.

The Industrial and Commercial Union (ICU) was a trade union and mass-based popular political movement in southern Africa. It was influenced by the syndicalist politics of the Industrial Workers of the World, as well as by Garveyism, Christianity, communism, and liberalism.

The Agricultural Workers Organization (AWO), later known as the Agricultural Workers Industrial Union, was an organization of farm workers throughout the United States and Canada formed on April 15, 1915, in Kansas City. It was supported by, and a subsidiary organization of, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Although the IWW had advocated the abolition of the wage system as an ultimate goal since its own formation ten years earlier, the AWO's founding convention sought rather to address immediate needs, and championed a ten-hour work day, premium pay for overtime, a minimum wage, good food and bedding for workers. In 1917 the organization changed names to the Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (AWIU) as part of a broader reorganization of IWW industrial unions.

The Syndicalist League of North America was an organization led by William Z. Foster that aimed to "bore from within" the American Federation of Labor to win that trade union center over to the ideals of Revolutionary syndicalism.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is a union of wage workers which was formed in Chicago in 1905. The IWW experienced a number of divisions and splits during its early history.

The International Socialist League of South Africa was the earliest major Marxist party in South Africa, and a predecessor of the South African Communist Party. The ISL was founded around the syndicalist politics of the Industrial Workers of the World and Daniel De Leon.

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions of political, social, and labour organizations and may also include rallies, marches, boycotts, civil disobedience, non-payment of taxes, and other forms of direct or indirect action. Additionally, general strikes might exclude care workers, such as teachers, doctors, and nurses.

Anarchism in Austria first developed from the anarchist segments of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), eventually growing into a nationwide anarcho-syndicalist movement that reached its height during the 1920s. Following the institution of fascism in Austria and the subsequent war, the anarchist movement was slow to recover, eventually reconstituting anarcho-syndicalism by the 1990s.