The Battle of Marais des Cygnes took place on October 25, 1864, in Linn County, Kansas, during Price's Missouri Raid in the American Civil War. It is also known as the Battle of Trading Post. In late 1864, Confederate Major General Sterling Price invaded the state of Missouri with a cavalry force, attempting to draw Union troops away from the primary theaters of fighting further east. After several victories early in the campaign, Price's Confederate troops were defeated at the Battle of Westport on October 23 near Kansas City, Missouri. The Confederates then withdrew into Kansas, camping along the banks of the Marais des Cygnes River on the night of October 24. Union cavalry pursuers under Brigadier General John B. Sanborn skirmished with Price's rearguard that night, but disengaged without participating in heavy combat.

The Battle of Mine Creek, also known as the Battle of Little Osage, was fought on October 25, 1864, in Linn County, Kansas, as part of Price's Missouri Expedition during the American Civil War. Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army had begun an expedition in September 1864 to restore Confederate control of Missouri. After being defeated at the Battle of Westport near Kansas City, Missouri, on October 23, Price's army began to retreat south through Kansas. Early on October 25, Price's army was defeated at the Battle of Marais des Cygnes. After Marais des Cygnes, the Confederates fell back, but were stalled at the crossing of Mine Creek while a wagon train attempted to cross.

The Battle of Westport, sometimes referred to as the "Gettysburg of the West", was fought on October 23, 1864, in modern Kansas City, Missouri, during the American Civil War. Union forces under Major General Samuel R. Curtis decisively defeated an outnumbered Confederate force under Major General Sterling Price. This engagement was the turning point of Price's Missouri Expedition, forcing his army to retreat. The battle ended the last major Confederate offensive west of the Mississippi River, and for the remainder of the war the United States Army maintained solid control over most of Missouri. This battle was one of the largest to be fought west of the Mississippi River, with over 30,000 men engaged.

The Battle of Clark's Mill was fought on November 7, 1862, near Vera Cruz, Missouri, as part of the American Civil War. Confederate troops led by Colonels Colton Greene and John Q. Burbridge were recruiting in the Gainesville area. Federal Captain Hiram E. Barstow commanded a detachment at Clark's Mill near Vera Cruz, and heard rumors of Confederate depredations around Gainesville. In response, Barstow sent patrols towards Gainesville and Rockbridge, personally accompanying the latter. Confederate forces were encountered before reaching Rockbridge, and Barstow fell back to Clark's Mill. The Confederates arrived from multiple directions, and after a skirmish of five hours, surrounded the Federal position. With night falling, the Confederates offered Barstow surrender terms that were accepted. The Federal soldiers were paroled and their blockhouse destroyed; both Barstow and the Confederates left the area after the skirmish. A Federal counterstroke left Ozark the next day.

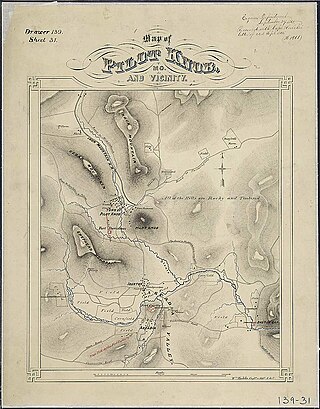

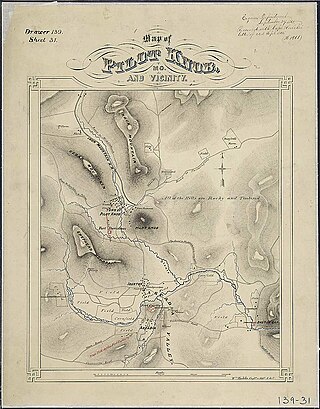

The Battle of Fort Davidson, also known as the Battle of Pilot Knob, was a battle of Price's Raid fought on September 27, 1864, near Pilot Knob, Missouri. Confederate troops under the command of Major General Sterling Price had entered Missouri in September 1864 with hopes of challenging Union control of the state. On September 24, Price learned that Union troops held Pilot Knob. Two days later, he sent part of his command north to disrupt and then moved towards Pilot Knob with the rest of his army. The Confederate divisions of Major General James F. Fagan and Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke drove Union troops under Brigadier General Thomas Ewing Jr. and Major James Wilson from the lower Arcadia Valley into Fort Davidson on September 26 and on the morning of September 27.

The Second Battle of Independence was fought on October 22, 1864, near Independence, Missouri, as part of Price's Raid during the American Civil War. In late 1864, Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army led a cavalry force into the state of Missouri in the hopes of creating a popular uprising against Union control, drawing Union Army troops from more important areas, and influencing the 1864 United States presidential election. Price was opposed by a combination of Union Army and Kansas State Militia forces positioned near Kansas City and led by Major General Samuel R. Curtis; Union cavalry under Major General Alfred Pleasonton followed Price from the east, working to catch up to the Confederates from the rear. While moving westwards along the Missouri River, Price's men made contact with Curtis's Union troops at the Little Blue River on October 21. After forcing the Union soldiers to retreat in the Battle of Little Blue River, the Confederates occupied the city of Independence, which was 7 miles (11 km) away.

The Second Battle of Lexington was a minor battle fought during Price's Raid as part of the American Civil War. Hoping to draw Union Army forces away from more important theaters of combat and potentially affect the outcome of the 1864 United States presidential election, Sterling Price, a major general in the Confederate States Army, led an offensive into the state of Missouri on September 19, 1864. After a botched attack at the Battle of Pilot Knob, the strength of the Union defenses at Jefferson City led Price to abandon the main goals of his campaign.

The Battle of Little Blue River was fought on October 21, 1864, as part of Price's Raid during the American Civil War. Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army led an army into Missouri in September 1864 with hopes of challenging Union control of the state. During the early stages of the campaign, Price abandoned his plan to capture St. Louis and later his secondary target of Jefferson City. The Confederates then began moving westwards, brushing aside Major General James G. Blunt's Union force in the Second Battle of Lexington on October 19. Two days later, Blunt left part of his command under the authority of Colonel Thomas Moonlight to hold the crossing of the Little Blue River, while the rest of his force fell back to Independence. On the morning of October 21, Confederate troops attacked Moonlight's line, and parts of Brigadier General John B. Clark Jr.'s brigade forced their way across the river. A series of attacks and counterattacks ensued, neither side gaining a significant advantage.

The Battle of Marmiton River, also known as Shiloh Creek or Charlot's Farm, occurred on October 25, 1864, in Vernon County, Missouri during the American Civil War. Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army commenced an expedition into Missouri in September 1864, with hopes of challenging Union control of the state. After a defeat at the Battle of Westport on October 23, Price began to retreat south, and suffered a serious defeat at the Battle of Mine Creek early on October 25. The afternoon of the 25th, Price's wagon train became stalled at the crossing of the Marmaton River in western Missouri. A delaying force led by Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby attempted to hold off Union cavalry commanded by Brigadier General John McNeil and Lieutenant Colonel Frederick W. Benteen. Shelby was unable to drive off the Union force, although fatigue of the Union cavalry's horses prevented close-quarters action. At nightfall, the Confederates disengaged and destroyed much of their wagon train. Price was again defeated on October 28 at the Second Battle of Newtonia, and the Confederate retreat continued until the survivors reached Texas in early December.

The Battle of Byram's Ford was fought on October 22 and 23, 1864, in Missouri during Price's Raid, a campaign of the American Civil War. With the Confederate States of America collapsing, Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army conducted an invasion of the state of Missouri in late 1864. Union forces led Price to abandon goals of capturing the cities of St. Louis and Jefferson City, and he turned west with his army towards Kansas City.

The Second Battle of Newtonia was fought on October 28, 1864, near Newtonia, Missouri, between cavalry commanded by Major General James G. Blunt of the Union Army and Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby's rear guard of the Confederate Army of Missouri. In September 1864, Confederate Major General Sterling Price had entered the state of Missouri with hopes of creating a popular uprising against Union control of the state. A defeat at the Battle of Pilot Knob in late September and the strength of Union positions at Jefferson City led Price to abandon the main objectives of the campaign; instead he moved his force west towards Kansas City, where it was badly defeated at the Battle of Westport by Major General Samuel R. Curtis on October 23. Following a set of three defeats on October 25, Price's army halted to rest near Newtonia on October 28.

Price's Missouri Expedition, also known as Price's Raid or Price's Missouri Raid, was an unsuccessful Confederate cavalry raid through Arkansas, Missouri, and Kansas in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War. Led by Confederate Major-General Sterling Price, the campaign's intention was to recapture Missouri and renew the Confederate initiative in the larger conflict.

Fort Davidson, a fortification near the town of Pilot Knob, Missouri, was the site of the Battle of Fort Davidson during the American Civil War. Built by Union Army soldiers during the American Civil War, the fort repulsed Confederate attacks during the Battle of Fort Davidson on September 27, 1864, during Price's Raid. That night, the Union garrison blew up the fort's magazine and abandoned the site. A mass grave was constructed on the site to bury battlefield dead. After the war, the area was used by a mining company, before passing into private hands and eventually the administration of the United States Forest Service. In 1968, the Battle of Pilot Knob State Historic Site was created as a Missouri State Park. The fort itself was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970. As of 2020, a visitors center containing a museum is located within the park. The museum contains a fiber optic display, as well as artifacts including Brigadier General Thomas Ewing Jr.'s sword. The fort's walls are still visible, as is the crater created when the magazine was detonated. A monument marks the location of the mass grave.

Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Regiment was a cavalry regiment of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Originally formed as Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Battalion, the unit consisted of men recruited in Missouri by Lieutenant Colonel Alonzo W. Slayback during Price's Raid in 1864. The battalion's first action was at the Battle of Pilot Knob on September 27; it later participated in actions at Sedalia, Lexington, and the Little Blue River. In October, the unit was used to find an alternate river crossing during the Battle of the Big Blue River. Later that month, Slayback's unit saw action at the battles of Westport, Marmiton River, and Second Newtonia. The battalion was briefly furloughed in Arkansas before rejoining Major General Sterling Price in Texas in December. Probably around February 1865, the battalion reached official regimental strength after more recruits joined.

The capture of Sedalia occurred during the American Civil War when a Confederate force captured the Union garrison of Sedalia, Missouri, on October 15, 1864. Confederate Major General Sterling Price, who was a former Governor of Missouri and had commanded the Missouri State Guard in the early days of the war, had launched an invasion into the state of Missouri on August 29. He hoped to distract the Union from more important areas and cause a popular uprising against Union control of the state. Price had to abandon his goal of capturing St. Louis after a bloody repulse at the Battle of Fort Davidson and moved into the pro-Confederate region of Little Dixie in central Missouri.

The Second Battle of Newtonia Site is a battlefield listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) near Newtonia and Stark City in Missouri. In late 1864, Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army began a raid into Missouri in hopes of diverting Union troops away from more important theaters of the American Civil War. After a defeat at the Battle of Westport on October 23, Price's Army of Missouri began retreating through Kansas, but suffered three consecutive defeats on October 25. By October 28, the retreating Confederates had reached Newtonia, where the Second Battle of Newtonia broke out when Union pursuers caught up with the Confederates. Confederate cavalry under Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby was initially successful, but after Union reinforcements under Brigadier General John B. Sanborn counterattacked, the Confederates withdrew. The Union troops did not pursue, and Price's men escaped, eventually reaching Texas by December.

Nichols's Missouri Cavalry Regiment served in the Confederate States Army during the late stages of the American Civil War. The cavalry regiment began recruiting in early 1864 under Colonel Sidney D. Jackman, who had previously raised a unit that later became the 16th Missouri Infantry Regiment. The regiment officially formed on June 22 and operated against the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad through August. After joining Major General Sterling Price's command, the unit participated in Price's Raid, an attempt to create a popular uprising against Union control of Missouri and draw Union troops away from more important theaters of the war. During the raid, while under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Charles H. Nichols, the regiment was part of an unsuccessful pursuit of Union troops who were retreating after the Battle of Fort Davidson in late September.

The 13th Missouri Cavalry Regiment was a cavalry unit that served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. In early April 1863, Captain Robert C. Wood, aide-de-camp to Confederate Major General Sterling Price, was detached to form an artillery unit from some of the men of Price's escort. Wood continued recruiting for the unit, which was armed with four Williams guns, and grew to 275 men by the end of September. The next month, the unit fought in the Battle of Pine Bluff, driving back Union Army troops into a barricaded defensive position, from which the Union soldiers could not be dislodged. By November, the unit, which was known as Wood's Missouri Cavalry Battalion, had grown to 400 men but no longer had the Williams guns. In April 1864, Wood's battalion, which was also known as the 14th Missouri Cavalry Battalion, played a minor role in the defeat of a Union foraging party in the Battle of Poison Spring, before spending the summer of 1864 at Princeton, Arkansas. In September, the unit joined Price's Raid into the state of Missouri, but their assault during the Battle of Pilot Knob failed to capture Fort Davidson.

The 10th Texas Field Battery was an artillery battery that served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. After being formed in early 1861 by Benjamin H. Pratt, the battery served with a cavalry formation led by Colonel William Henry Parsons for part of 1862. It was called upon to enter Missouri in support of troop movements related to the Battle of Prairie Grove, but this did not occur. It then operated along the Mississippi River in early 1863, harassing enemy shipping. The unit then participated in Marmaduke's Second Expedition into Missouri and the Battle of Pine Bluff in 1863. Late in 1864, the battery, now under the command of H. C. Hynson, served in Price's Raid, participating in several battles and skirmishes, including the disastrous Battle of Mine Creek. One source claims the unit's service ended on May 26, 1865, while a Confederate report dated June 1, 1865, states that it existed but did not have cannons. Confederate forces in the Trans-Mississippi Department surrendered on June 2.

The Last Hurrah: Sterling Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 is a 2015 book written by Kyle Sinisi and published by Rowman & Littlefield about Price's Missouri Expedition, an 1864 campaign of the American Civil War that failed to wrest control of the state of Missouri from the Union. Sinisi focused on the military expedition itself, but also covered political machinations that occurred during the expedition as well as topography and logistics. The Last Hurrah posits that the campaign should not be viewed as a raid due to its magnitude, that the Battle of Mine Creek had elements of a massacre, and that Missouri did not want to give up Union control. Reviewers praised the work, especially its ability to cover the campaign comprehensively while also discussing factors such as politics and the effects of guerrilla warfare.