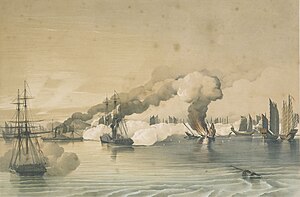

The Battle of Fuzhou, or Battle of Foochow, also known as the Battle of the Pagoda Anchorage, was the opening engagement of the 16-month Sino-French War. The battle was fought on 23 August 1884 off the Pagoda Anchorage in Mawei (馬尾) harbour, 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) to the southeast of the city of Fuzhou (Foochow). During the battle Admiral Amédée Courbet's Far East Squadron virtually destroyed the Fujian Fleet, one of China's four regional fleets.

Cheung Po Tsai was a navy colonel of the Qing dynasty and a former pirate. "Cheung Po Tsai" literally means "Cheung Po the Kid". He was known to the Portuguese Navy as Quan Apon Chay during the Battle of the Tiger's Mouth.

The naval history of China dates back thousands of years, with archives existing since the late Spring and Autumn period regarding the Chinese navy and the various ship types employed in wars. The Ming dynasty of China was the leading global maritime power between 1400 and 1433, when Chinese shipbuilders built massive ocean-going junks and the Chinese imperial court launched seven maritime voyages. In modern times, the current People's Republic of China and the Republic of China governments continue to maintain standing navies through the People's Liberation Army Navy and the Republic of China Navy, respectively.

Shap-ng-tsai was a Chinese pirate active in the South China Sea from about 1845 to 1859. He was one of the two most notorious South China Sea pirates of the era, along with Chui A-poo. He commanded about 70 junks stationed at Dianbai, about 180 miles west of Hong Kong. Coastal villages and traders paid Shap-ng-tsai protection money so they would not be attacked. Chinese naval ships that pursued the pirate were captured and their officers taken captive and held for ransom. The Chinese government offered him a pardon and the rank of officer in the military at first he did not accept, but he eventually did so to avoid legal ramifications.

The Battle of Liaoluo Bay took place in 1633 off the coast of Fujian, China; involving the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Chinese Ming dynasty's navies. The battle was fought at the crescent-shaped Liaoluo Bay that forms the southern coast of the island of Kinmen. A Dutch fleet under Admiral Hans Putmans was attempting to control shipping in the Taiwan Strait, while the southern Fujian sea traffic and trade was protected by a fleet under Brigadier General Zheng Zhilong. This was the largest naval encounter between Chinese and European forces before the Opium Wars two hundred years later.

The Guangdong Fleet was the smallest of China's four regional fleets during the second half of the nineteenth century. The fleet played virtually no part in the Sino-French War, but several of its ships saw action in the Sino-Japanese War (1894–5).

Cai Qian was a Chinese sea merchant, considered by some a pirate during the Qing dynasty era.

Chui A-poo was a 19th-century Qing Chinese pirate who commanded a fleet of more than 50 junks in the South China Sea. He was one of the two most notorious South China Sea pirates of the era, along with Shap Ng-tsai.

The Battle of Ty-ho Bay was a significant naval engagement in 1855 involving the United Kingdom and United States against Chinese pirates. The action off Tai O, Hong Kong was to rescue captured merchant vessels, held by a fleet of armed war-junks. British and American forces defeated the pirates in one of the last major battles between Chinese pirate fleets and western navies. It was also one of the first joint operations undertaken by British and American forces.

The Battle of the Leotung was a British victory against an overwhelming fleet of Chinese pirate ships. In 1855 the Royal Navy launched a series of operations into the Gulf of Leotung and surrounding area to suppress piracy, several battles were fought and hundreds of pirates were killed.

The Battle of Tysami was a military engagement involving a warship from the British China Squadron and the Chinese pirates of Chui A-poo. It was fought in September 1849 off Tysami, Harlaim Bay, China, and ended with a Royal Navy victory. It was also the precursor engagement to the larger Battle of Pinghoi Creek where Chui A-poo's fleet was destroyed.

The West Indies Squadron, or the West Indies Station, was a United States Navy squadron that operated in the West Indies in the early nineteenth century. It was formed due to the need to suppress piracy in the Caribbean Sea, the Antilles and the Gulf of Mexico region of the Atlantic Ocean. This unit later engaged in the Second Seminole War until being combined with the Home Squadron in 1842. From 1822 to 1826 the squadron was based out of Saint Thomas Island until the Pensacola Naval Yard was constructed.

The Lapérouse class was a group of four wooden-hulled unprotected cruisers of the French Navy built in the mid-1870s and early 1880s. The class comprised Lapérouse—the lead ship—D'Estaing, Nielly, and Primauguet. They were designed to operate overseas in the French colonial empire, and they were ordered as part of a construction program intended to strengthen the fleet after the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. They carried a main battery of fifteen 138.6 mm (5.46 in) guns, had a top speed of 15 knots, and had a full ship rig to supplement their steam engines during lengthy voyages abroad.

The Battle of Nam Quan was fought in 1853 as part of a British anti-piracy operation in China. A Royal Navy sloop-of-war encountered eight pirate ships near Nam Quan and defeated them in a decisive action with help from armed Chinese civilians on land.

Aegean Sea anti-piracy operations began in 1825 when the United States government dispatched a squadron of ships to suppress Greek piracy in the Aegean Sea. The Greek civil wars of 1824–1825 and the decline of the Hellenic Navy made the Aegean quickly become a haven for pirates who sometimes doubled as privateers.

The West Indies Anti-Piracy Operations were a series of military operations and engagements undertaken by the United States Navy against pirates in and around the Antilles. Between 1814 and 1825, the American West Indies Squadron hunted pirates on both sea and land, primarily around Cuba and Puerto Rico. After the capture of Roberto Cofresi in 1825, acts of piracy became rare, and the operation was considered a success, although limited occurrences went on until slightly after the start of the 20th century.

The Irene incident was a 1927 British anti-piracy operation in China. In an attempt to surprise the pirates of Bias Bay about sixty miles from British Hong Kong, Royal Navy submarines attacked the steamship SS Irene, of the China Merchants Steam Navigation Company, which had been taken over by the pirates on the night of 19 October. The British were successful in thwarting the hijacking though they sank the ship.

Ying Rui was a protected cruiser built for the Imperial Chinese Navy, which served with the Republic of China Navy. She was built by Vickers Limited in Barrow-in-Furness, England. She was one of three Chao Ho class protected cruisers built, although each one was to different specifications. Initially designated as a training vessel, she saw action at Amoy during the Warlord era, before returning again to her training role.

Pirates of the South China Coast were Chinese pirates who were active in the north-western coasts of the South China Sea from the late 18th century to the 19th century, mainly during a 20-year period from 1790 to 1810. After 1805, the pirates of the South China Coast entered their most powerful period. Many pirates were fully trained by the Tây Sơn dynasty of Vietnam.

The Battle of the Tiger's Mouth was a series of engagements between a Portuguese flotilla stationed in Macau, and the Red Flag Fleet of the Chinese pirate Ching Shih, led by her second-in-command, Cheung Po Tsai - known to the Portuguese as Cam Pau Sai or Quan Apon Chay. Between September 1809 and January 1810, the Red Flag Fleet suffered several defeats at the hands of the Portuguese fleet led by José Pinto Alcoforado e Sousa, within the Humen Strait - known to the Portuguese as the Boca do Tigre - until finally surrendering formally in February 1810. After her fleet surrendered, Ching Shih surrendered herself to the Qing government in exchange for a general pardon, putting an end to her career of piracy.