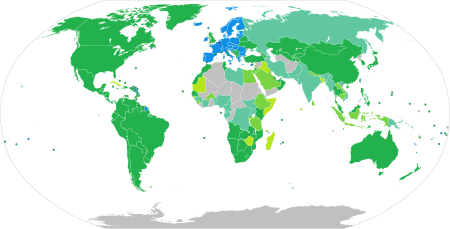

Jus soli, commonly referred to as birthright citizenship, is the right to acquire nationality or citizenship by being born within the territory of a state.

In international law, a stateless person is someone who is "not considered as a national by any state under the operation of its law". Some stateless people are also refugees. However, not all refugees are stateless, and many people who are stateless have never crossed an international border. At the end of 2022, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated 4.4 million people worldwide as either stateless or of undetermined nationality, 90,800 more than at the end of 2021.

Swiss citizenship is the status of being a citizen of Switzerland and it can be obtained by birth or naturalisation.

The primary law governing nationality of the Republic of Ireland is the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act, 1956, which came into force on 17 July 1956. Ireland is a member state of the European Union (EU) and all Irish nationals are EU citizens. They are entitled to free movement rights in EU and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries and may vote in elections to the European Parliament.

French nationality law is historically based on the principles of jus soli and jus sanguinis, according to Ernest Renan's definition, in opposition to the German definition of nationality, jus sanguinis, formalised by Johann Gottlieb Fichte.

Dutch nationality law details the conditions by which a person holds Dutch nationality. The primary law governing these requirements is the Dutch Nationality Act, which came into force on 1 January 1985. Regulations apply to the entire Kingdom of the Netherlands, which includes the country of the Netherlands itself, Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten.

Swedish nationality law determines entitlement to Swedish citizenship. Citizenship of Sweden is based primarily on the principle of jus sanguinis. In other words, citizenship is conferred primarily by birth to a Swedish parent, irrespective of place of birth.

Portuguese nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a national of Portugal. The primary law governing nationality regulations is the Nationality Act, which came into force on 3 October 1981.

Maltese nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a national of Malta. The primary law governing nationality regulations is the Maltese Citizenship Act, which came into force on 21 September 1964. Malta is a member state of the European Union (EU) and all Maltese nationals are EU citizens. They have automatic and permanent permission to live and work in any EU or European Free Trade Association (EFTA) country and may vote in elections to the European Parliament.

Icelandic nationality law details the conditions by which an individual is a national of Iceland. The primary law governing these requirements is the Icelandic Nationality Act, which came into force on 1 January 1953. Iceland is a member state of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). All Icelandic nationals have automatic and permanent permission to live and work in any European Union (EU) or EFTA country.

Slovenian nationality law is based primarily on the principles of jus sanguinis, in that descent from a Slovenian parent is the primary basis for acquisition of Slovenian citizenship. However, although children born to foreign parents in Slovenia do not acquire Slovenian citizenship on the basis of birthplace, place of birth is relevant for determining whether the child of Slovenian parents acquires citizenship.

Hungarian nationality law is based on the principles of jus sanguinis. Hungarian citizenship can be acquired by descent from a Hungarian parent, or by naturalisation. A person born in Hungary to foreign parents does not generally acquire Hungarian citizenship. A Hungarian citizen is also a citizen of the European Union.

Belarusian nationality law regulates the manner in which one acquires, or is eligible to acquire, Belarusian nationality, citizenship. Belarusian citizenship is membership in the political community of the Republic of Belarus.

Ukrainian nationality law details the conditions by which a person holds nationality of Ukraine. The primary law governing these requirements is the law "On Citizenship of Ukraine", which came into force on 1 March 2001.

Luxembourg nationality law is ruled by the Constitution of Luxembourg. The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg is a member state of the European Union and, therefore, its citizens are also EU citizens.

Monégasque nationality law determines entitlement to Monégasque citizenship. Citizenship of Monaco is based primarily on the principle of jus sanguinis. In other words, citizenship is conferred primarily by birth to a Monégasque parent, irrespective of place of birth.

Thai nationality law includes principles of both jus sanguinis and jus soli. Thailand's first Nationality Act was passed in 1913. The most recent law dates to 2008.

I-Kiribati nationality law is regulated by the 1979 Constitution of Kiribati, as amended; the 1979 Citizenship Act, and its revisions; and various British Nationality laws. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Kiribati. I-Kiribati nationality is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in Kiribati or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth abroad to parents with I-Kiribati nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalisation. Nationality establishes one's international identity as a member of a sovereign nation. Though it is not synonymous with citizenship, for rights granted under domestic law for domestic purposes, the United Kingdom, and thus the Commonwealth, have traditionally used the words interchangeably.

Seychellois nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Seychelles, as amended; the Citizenship Act, and its revisions; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Seychelles. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. In Britain and thus the Commonwealth of Nations, though the terms are often used synonymously outside of law, they are governed by different statutes and regulated by different authorities. Seychellois nationality is typically obtained under the principal of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth in Seychelles or abroad to parents with Seychellois nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalisation or registration.

Zambian nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Zambia, as amended; the Citizenship of Zambia Act; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Zambia. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. Commonwealth countries often use the terms nationality and citizenship as synonyms, despite their legal distinction and the fact that they are regulated by different governmental administrative bodies. Zambian nationality is typically obtained under the principals of jus soli, i.e. birth in Zambia, or jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth to parents with Zambian nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through registration.