Thomas Jefferson was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence. Following the American Revolutionary War and prior to becoming president in 1801, Jefferson was the nation's first U.S. secretary of state under George Washington and then the nation's second vice president under John Adams.

Sarah "Sally" Hemings was an enslaved woman with one-quarter African ancestry owned by president of the United States Thomas Jefferson, one of many he inherited from his father-in-law, John Wayles.

The quotation "all men are created equal" is found in the United States Declaration of Independence. The final form of the sentence was stylized by Benjamin Franklin and penned by Thomas Jefferson during the beginning of the Revolutionary War in 1776. It reads:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

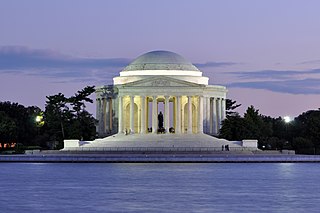

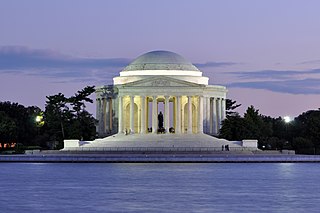

The Jefferson Memorial is a presidential memorial built in Washington, D.C., between 1939 and 1943 in honor of Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence, a central intellectual force behind the American Revolution, founder of the Democratic-Republican Party, and the nation's third president.

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, which meant opposition to what they considered to be artificial aristocracy, opposition to corruption, and insistence on virtue, with a priority for the "yeoman farmer", "planters", and the "plain folk". They were antagonistic to the aristocratic elitism of merchants, bankers, and manufacturers, distrusted factory workers, and strongly opposed and were on the watch for supporters of the Westminster system.

Martha Skelton Jefferson was the wife of Thomas Jefferson from 1772 until her death. She served as First Lady of Virginia during Jefferson's term as governor from 1779 to 1781. She died in 1782, 19 years before he became president.

The American Enlightenment was a period of intellectual and philosophical fervor in the thirteen American colonies in the 18th to 19th century, which led to the American Revolution and the creation of the United States of America. The American Enlightenment was influenced by the 17th- and 18th-century Age of Enlightenment in Europe and native American philosophy. According to James MacGregor Burns, the spirit of the American Enlightenment was to give Enlightenment ideals a practical, useful form in the life of the nation and its people.

The values and ideals of republicanism are foundational in the constitution and history of the United States. As the United States constitution prohibits granting titles of nobility, republicanism in this context does not refer to a political movement to abolish such a social class, as it does in countries such as the UK, Australia, and the Netherlands. Instead, it refers to the core values that citizenry in a republic have, or ought to have.

Thomas Mann Randolph Jr. was an American planter, soldier, and politician from Virginia. He served as a member of both houses of the Virginia General Assembly, a representative in the United States Congress, and as the 21st governor of Virginia, from 1819 to 1822. He married Martha Jefferson, the oldest daughter of Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States. They had eleven children who survived childhood. As an adult, Randolph developed alcoholism, and he and his wife separated for some time before his death.

Jeffersonian architecture is an American form of Neo-Classicism and/or Neo-Palladianism embodied in the architectural designs of U.S. President and polymath Thomas Jefferson, after whom it is named. These include his home (Monticello), his retreat, the university he founded, and his designs for the homes of friends and political allies. More than a dozen private homes bearing his personal stamp still stand today. Jefferson's style was popular in the early American period at about the same time that the more mainstream Greek Revival architecture was also coming into vogue (1790s–1830s) with his assistance.

Bremo, also known as Bremo Plantation or Bremo Historic District, is a plantation estate covering over 1,500 acres (610 ha) on the west side of Bremo Bluff in Fluvanna County, Virginia. The plantation includes three separate estates, all created in the 19th century by the planter, soldier, and reformer John Hartwell Cocke on his family's 1725 land grant. The large neo-palladian mansion at "Upper" Bremo was designed by Cocke in consultation with John Neilson, a master joiner for Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. The Historic District also includes two smaller residences known as Lower Bremo and Bremo Recess.

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, owned more than 600 slaves during his adult life. Jefferson freed two slaves while he lived, and five others were freed after his death, including two of his children from his relationship with his slave Sally Hemings. His other two children with Hemings were allowed to escape without pursuit. After his death, the rest of the slaves were sold to pay off his estate's debts.

A Polygraph is a duplicating device that produces a copy of a piece of writing simultaneously with the creation of the original, using pens and ink.

John Wayles was a colonial American planter, slave trader and lawyer in colonial Virginia. He is historically best known as the father-in-law of Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States. Wayles married three times, with these marriages producing eleven children; only five of them lived to adulthood. Through his female slave Betty Hemings, Wayles fathered six additional children, including Sally Hemings, who was the mother of six children by Thomas Jefferson and half-sister of Martha Jefferson.

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, was involved in politics from his early adult years. This article covers his early life and career, through his writing the Declaration of Independence, participation in the American Revolutionary War, serving as governor of Virginia, and election and service as Vice-President to President John Adams.

Historical accounts for early U.S. naval history now occur across the spectrum of two and more centuries. This Bibliography lends itself primarily to reliable sources covering early U.S. naval history beginning around the American Revolution period on through the 18th and 19th centuries and includes sources which cover notable naval commanders, Presidents, important ships, major naval engagements and corresponding wars. The bibliography also includes sources that are not committed to the subject of U.S. naval history per se but whose content covers this subject extensively.

Edmund Bacon (1785–1866), was the business manager and primary overseer for 20 years for Thomas Jefferson, third President of the United States, at Monticello. Among some of his other business duties, Bacon supervised the daily chores and activities of farming and ranching at Monticello along with Jefferson's nail forge. His duties included supervising and providing supplies and other needs for Jefferson's slaves. When he retired, Bacon moved to Kentucky and was discovered by the author Rev. Hamilton Pierson, who made use of his memoirs and letters to write a book about Jefferson's personal life and character. The memoirs of Bacon's life at Monticello has given much insight into the daily activities there, as well as into Jefferson's life and personality.

The Papers of Thomas Jefferson is a multi-volume scholarly edition devoted to the publication of the public and private papers of Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States. The project, established at Princeton University, is the definitive edition of documents written by or to Jefferson. Work on the series began in 1944 and was undertaken solely at Princeton until 1998, when responsibility for editing documents from Jefferson's post-presidential retirement years, 1809 until 1826, shifted to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello. This enabled work to progress simultaneously on two different periods of Jefferson's life and thereby doubled the production of volumes without compromising the high standards set for the project.

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, originally known as the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, is a private, nonprofit 501(c)(3) corporation founded in 1923 to purchase and maintain Monticello, the primary plantation of Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States. The Foundation's initial focus was on architectural preservation, with the goal of restoring Monticello as close to its original appearance as possible. It has since grown to include other historic and cultural pursuits and programs such as its Annual Independence Day Celebration and Naturalization Ceremony. It also publishes and provides a center for scholarship on Jefferson and his era.

The following article covers the historiography and general reputation of Thomas Jefferson, Founding Father and 3rd president of the United States.