Thomas Jefferson was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence. Following the American Revolutionary War and prior to becoming president in 1801, Jefferson was the nation's first U.S. secretary of state under George Washington and then the nation's second vice president under John Adams.

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his Academical Village, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The original governing Board of Visitors included three U.S. presidents: Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, the latter as sitting president of the United States at the time of its foundation. As its first two rectors, Presidents Jefferson and Madison played key roles in the university's foundation, with Jefferson designing both the original courses of study and the university's architecture. Located within its historic 1,135 acre central campus, the university is composed of eight undergraduate and three professional schools: the School of Law, the Darden School of Business, and the School of Medicine.

William Holmes McGuffey was an American college professor and president who is best known for writing the McGuffey Readers, the first widely used series of elementary school-level textbooks. More than 120 million copies of McGuffey Readers were sold between 1836 and 1960, placing its sales in a category with the Bible and Webster's Dictionary.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 was adopted by the United States Congress of the Confederation on May 20, 1785. It set up a standardized system whereby settlers could purchase title to farmland in the undeveloped west. Congress at the time did not have the power to raise revenue by direct taxation, so land sales provided an important revenue stream. The Ordinance set up a survey system that eventually covered over three-quarters of the area of the continental United States.

"Separation of church and state" is a metaphor paraphrased from Thomas Jefferson and used by others in discussions regarding the Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution which reads: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof..."

Thomas Jefferson is a 1997 two-part American documentary film directed and produced by Ken Burns. It covers the life and times of Thomas Jefferson, the 3rd President of the United States.

Notes on the State of Virginia (1785) is a book written by the American statesman, philosopher, and planter Thomas Jefferson. He completed the first version in 1781 and updated and enlarged the book in 1782 and 1783. It originated in Jefferson's responses to questions about Virginia, part of a series of questions posed to each of the thirteen states in 1780 by François Barbé-Marbois, the secretary of the French delegation in Philadelphia, the temporary capital of the Continental Congress.

Joseph Priestley was a British natural philosopher, Dissenting clergyman, political theorist, and theologian. While his achievements in all of these areas are renowned, he was also dedicated to improving education in Britain; he did this on an individual level and through his support of the Dissenting academies. His grammar textbook was innovative and highly influential. More importantly, though, Priestley introduced a liberal arts curriculum at Warrington Academy, arguing that a practical education would be more useful to students than a classical one. He was also the first to advocate the study and teaching of modern history, an interest driven by his belief that humanity was improving and could bring about Christ's Millennium.

James Hemings (1765–1801) was the first American to train as a chef in France. Three-quarters white in ancestry, he was born into slavery in Virginia in 1765. At eight years old, he was purchased by Thomas Jefferson at his residence of Monticello.

The Ordinance of 1784 called for the land in the recently created United States which was located west of the Appalachian Mountains, north of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi River to be divided into separate states.

The history of the College of William & Mary can be traced back to a 1693 royal charter establishing "a perpetual College of Divinity, Philosophy, Languages, and the good arts and sciences" in the British Colony of Virginia. It fulfilled an early colonial vision dating back to 1618 to construct a university level program modeled after Cambridge and Oxford at Henricus. A plaque on the Wren Building, the college's first structure, ascribes the institution's origin to "the college proposed at Henrico." It was named for the reigning joint monarchs of Great Britain, King William III and Queen Mary II. The selection of the new college's location on high ground at the center ridge of the Virginia Peninsula at the tiny community of Middle Plantation is credited to its first President, Reverend Dr. James Blair, who was also the Commissary of the Bishop of London in Virginia. A few years later, the favorable location and resources of the new school helped Dr. Blair and a committee of 5 students influence the House of Burgesses and Governor Francis Nicholson to move the capital there from Jamestown. The following year, 1699, the town was renamed Williamsburg.

The religious views of Thomas Jefferson diverged widely from the traditional Christianity of his era. Throughout his life, Jefferson was intensely interested in theology, religious studies, and morality. Jefferson was most comfortable with Deism, rational religion, theistic rationalism, and Unitarianism. He was sympathetic to and in general agreement with the moral precepts of Christianity. He considered the teachings of Jesus as having "the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man," yet he held that the pure teachings of Jesus appeared to have been appropriated by some of Jesus' early followers, resulting in a Bible that contained both "diamonds" of wisdom and the "dung" of ancient political agendas.

Education in Virginia addresses the needs of students from pre-kindergarten through adult education. Virginia's educational system consistently ranks in the top ten states on the U.S. Department of Education's National Assessment of Educational Progress, with Virginia students outperforming the average in almost all subject areas and grade levels tested. The 2010 Quality Counts report ranked Virginia's K–12 education fourth best in the country. All school divisions must adhere to educational standards set forth by the Virginia Department of Education, which maintains an assessment and accreditation regime known as the Standards of Learning to ensure accountability. In 2008, 81% of high school students graduated on-time after four years. The 1984 Virginia Assembly stated that, "Education is the cornerstone upon which Virginia's future rests."

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, owned more than 600 slaves during his adult life. Jefferson freed two slaves while he lived, and five others were freed after his death, including two of his children from his relationship with his slave Sally Hemings. His other two children with Hemings were allowed to escape without pursuit. After his death, the rest of the slaves were sold to pay off his estate's debts.

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, was involved in politics from his early adult years. This article covers his early life and career, through his writing the Declaration of Independence, participation in the American Revolutionary War, serving as governor of Virginia, and election and service as Vice-President to President John Adams.

Brigadier-General John Hartwell Cocke II was an American military officer, planter and businessman. During the War of 1812, Cocke served in the Virginia militia. After his military service, he invested in the James River and Kanawha Canal and helped Thomas Jefferson establish the University of Virginia. The family estate that Cocke built at Bremo Plantation is now a National Historic Landmark.

Thomas Jefferson believed Native American peoples to be a noble race who were "in body and mind equal to the whiteman" and were endowed with an innate moral sense and a marked capacity for reason. Nevertheless, he believed that Native Americans were culturally and technologically inferior. Like many contemporaries, he believed that Indian lands should be taken over by white people.

The history of the University of Virginia opens with its conception by Thomas Jefferson at the beginning of the early 19th century. The university was chartered in 1819, and classes commenced in 1825.

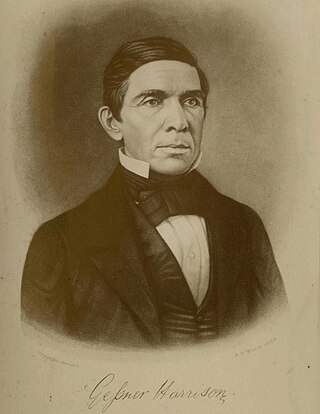

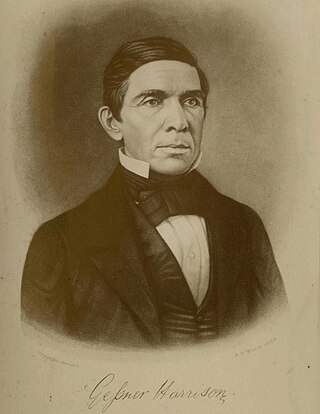

Gessner Harrison was an American educator, author, and college administrator during the antebellum era. He was appointed by James Madison as an associate professor of ancient languages at the University of Virginia (1828–1859). Harrison was recognized for teaching the fundamentals of the classics as well as linguistics, and for advancing these in his publications. He often served as chairman of the faculty and was required to address years of riotous student behavior.