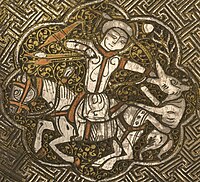

Islamic art is a part of Islamic culture and encompasses the visual arts produced since the 7th century CE by people who lived within territories inhabited or ruled by Muslim populations. Referring to characteristic traditions across a wide range of lands, periods, and genres, Islamic art is a concept used first by Western art historians in the late 19th century. Public Islamic art is traditionally non-representational, except for the widespread use of plant forms, usually in varieties of the spiralling arabesque. These are often combined with Islamic calligraphy, geometric patterns in styles that are typically found in a wide variety of media, from small objects in ceramic or metalwork to large decorative schemes in tiling on the outside and inside of large buildings, including mosques. Other forms of Islamic art include Islamic miniature painting, artefacts like Islamic glass or pottery, and textile arts, such as carpets and embroidery.

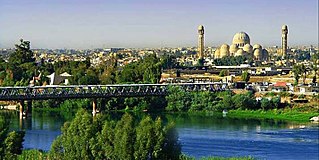

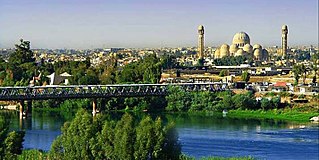

Mosul is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second-largest city in Iraq in terms of population and area after the capital Baghdad. Mosul is approximately 400 km (250 mi) north of Baghdad on the Tigris river. The Mosul metropolitan area has grown from the old city on the western side to encompass substantial areas on both the "Left Bank" and the "Right Bank", as locals call the two riverbanks. Mosul encloses the ruins of the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh – once the largest city in the world – on its east side.

The Zengid or Zangid dynasty was an Atabegate of the Seljuk Empire created in 1127. It formed a Turkoman dynasty of Sunni Muslim faith, which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia, and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169. In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripoli to Hamadan and from Yemen to Sivas. Imad ad-Din Zengi was the first ruler of the dynasty.

The Bobrinski Bucket, also called a kettle or cauldron, is a 12th-century bronze bucket originally manufactured for a merchant in Herat in 1163 out of bronze with copper and silver inlaid decorations. It provides one of the earliest examples of Persian anthropomorphic calligraphy. It is named after a former owner, Count Bobrinsky, and is now in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.

The Artuqid dynasty was established in 1102 as a Beylik (Principality) of the Seljuk Empire. It formed a Turkoman dynasty rooted in the Oghuz Döğer tribe, and followed the Sunni Muslim faith. It ruled in eastern Anatolia, Northern Syria and Northern Iraq in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries. The Artuqid dynasty took its name from its founder, Artuk Bey, who was of the Döger branch of the Oghuz Turks and ruled one of the Turkmen beyliks of the Seljuk Empire. Artuk's sons and descendants ruled the three branches in the region: Sökmen's descendants ruled the region around Hasankeyf between 1102 and 1231; Ilghazi's branch ruled from Mardin and Mayyafariqin between 1106 and 1186 and Aleppo from 1117–1128; and the Harput line starting in 1112 under the Sökmen branch, and was independent between 1185 and 1233.

In American English, a pitcher is a container with a spout used for storing and pouring liquids. In English-speaking countries outside North America, a jug is any container with a handle and a mouth and spout for liquid – American "pitchers" will be called jugs elsewhere. Generally a pitcher also has a handle, which makes pouring easier.

The Ghurid dynasty was a Persianate dynasty of presumably eastern Iranian Tajik origin, which ruled from the 8th-century in the region of Ghor, and became an Empire from 1175 to 1215. The Ghurids were centered in the hills of Ghor region in the present-day central Afghanistan, where they initially started out as local chiefs. They gradually converted to Sunni Islam after the conquest of Ghor by the Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud of Ghazni in 1011. The Ghurids eventually overran the Ghaznavids when Muhammad of Ghor seized Lahore and expelled the Ghaznavids from their last stronghold.

The Seljuk Empire, or the GreatSeljuk Empire, was a high medieval, culturally Turko-Persian, Sunni Muslim empire, established and ruled by the Qïnïq branch of Oghuz Turks. It spanned a total area of 3.9 million square kilometres from Anatolia and the Levant in the west to the Hindu Kush in the east, and from Central Asia in the north to the Persian Gulf in the south.

Qutb ad-Din Muhammad ibn al-Zangi was the Zengid Emir of Sinjar 1197–1219. He was successor of Imad ad-Din Zengi II.

Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I was the Zengid Emir of Mosul 1193–1211. He was successor of Izz al-Din Mas'ud. He was appointed by the Ayyubids to this position in 1193. One of his slaves was Badr ad-Din Lu'lu', who became a famous ruler of Mosul, and a prominent patron of the arts.

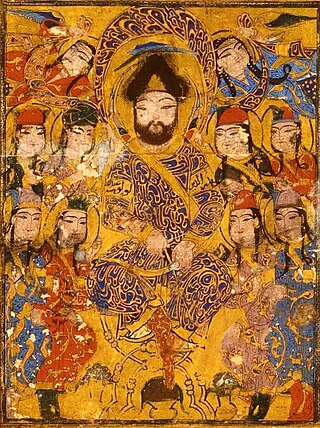

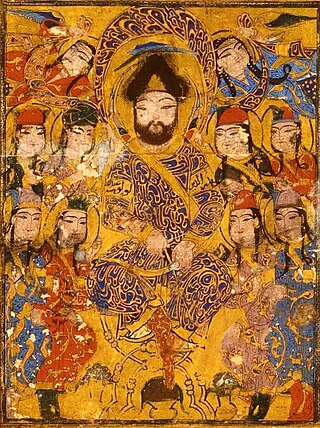

Badr al-Din Lu'lu' was successor to the Zengid emirs of Mosul, where he governed in variety of capacities from 1234 to 1259 following the death of Nasir ad-Din Mahmud. He was the founder of the short-lived Luluid dynasty. Originally a slave of the Zengid ruler Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I, he was the first Middle-Eastern mamluk to transcend servitude and become an emir in his own right, founding the dynasty of the Lu'lu'id emirs (1234-1262), and anticipating the rise of the Bahri Mamluks of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt by twenty years. He preserved control of al-Jazira through a series of tactical submissions to larger neighboring powers, at various times recognizing Ayyubid, Rûmi Seljuq, and Mongol overlords. His surrender to the Mongols after 1243 temporarily spared Mosul the destruction experienced by other settlements in Mesopotamia.

Gökböri, or Muzaffar ad-Din Gökböri, was a leading emir and general of Sultan Saladin, and ruler of Erbil. He served both the Zengid and Ayyubid rulers of Syria and Egypt. He played a pivotal role in Saladin's conquest of Northern Syria and the Jazira and later held major commands in a number of battles against the Crusader states and the forces of the Third Crusade. He was known as Manafaradin, a corruption of his principal praise name, to the Franks of the Crusader states.

Persian art or Iranian art has one of the richest art heritages in world history and has been strong in many media including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and sculpture. At different times, influences from the art of neighbouring civilizations have been very important, and latterly Persian art gave and received major influences as part of the wider styles of Islamic art. This article covers the art of Persia up to 1925, and the end of the Qajar dynasty; for later art see Iranian modern and contemporary art, and for traditional crafts see arts of Iran. Rock art in Iran is its most ancient surviving art. Iranian architecture is covered at that article.

The Baptistère de Saint Louis is an object of Islamic art, made of hammered brass, and inlaid with silver, gold, and niello. It was produced in the Syro-Egyptian zone, under the Mamluk dynasty by the coppersmith Muhammad ibn al-Zayn. This object is now in the Islamic Arts department of the Louvre under inventory number LP 16. Despite its common name, it has no connection with the King of France Louis IX, known as Saint Louis (1226–1270). It was used as a baptismal font for future French Kings, making it an important Islamic and French historical object.

During the thirteenth century, Mosul, Iraq became home to a school of luxury metalwork which rose to international renown. Artifacts classified as Mosul are some of the most intricately designed and revered pieces of the Middle Ages.

Mina'i ware is a type of Persian pottery, or Islamic pottery developed in Kashan, Iran, in the decades leading up to the Mongol invasion of Persia in 1219, after which production ceased. It has been described as "probably the most luxurious of all types of ceramic ware produced in the eastern Islamic lands during the medieval period". The ceramic body of white-ish fritware or stonepaste is fully decorated with detailed paintings using several colours, usually including figures.

Aḥmad ibn 'Umar al-Dhakī al-Mawṣilī was a 13th-century metalworker from Mosul, now in Iraq. He is known from three surviving works over a period of about 20 years from 1223 to 1242–43. He operated an atelier (workshop) with his ghulam Abu Bakr Umar ibn Hajji Jaldak. The epithet "al-Dhaki" means "the sagacious".

Izz al-Din Mas'ud II (r.1211–1218) was the son and successor of Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I, as Zengid dynasty ruler of the Mosul region in modern Iraq. He was only ten years old when he ascended the throne, and because of that was put under the control of a regent or atabeg by his dying father, in the person of one of his trusted mamluks, Badr al-Dīn Lū'lū'.

Nur al-Din Arslan Shah II (r.1218-1219) was the son and successor of Izz al-Din Mas'ud II, as Zengid dynasty ruler of the Mosul region in modern Iraq. He was under the control of a regent or atabeg, in the person of the mamluk, Badr al-Dīn Lū'lū'.