The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human culture from its beginnings to the present. The British Museum was the first public national museum to cover all fields of knowledge.

The Louvre, or the Louvre Museum, is a national art museum in Paris, France. It is located on the Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement and home to some of the most canonical works of Western art, including the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo. The museum is housed in the Louvre Palace, originally built in the late 12th to 13th century under Philip II. Remnants of the Medieval Louvre fortress are visible in the basement of the museum. Due to urban expansion, the fortress eventually lost its defensive function, and in 1546 Francis I converted it into the primary residence of the French kings.

Charles Townley FRS was a wealthy English country gentleman, antiquary and collector, a member of the Towneley family. He travelled on three Grand Tours to Italy, buying antique sculpture, vases, coins, manuscripts and Old Master drawings and paintings. Many of the most important pieces from his collection, especially the Townley Marbles are now in the British Museum's Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities. The marbles were overshadowed at the time, and still today, by the Elgin Marbles.

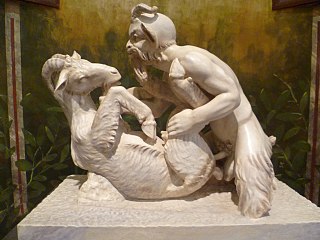

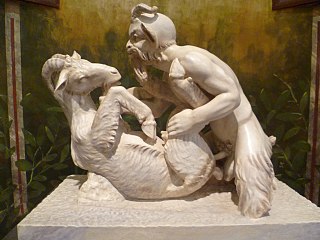

Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum has been both exhibited as art and censored as pornography. The Roman cities around the bay of Naples were destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, thereby preserving their buildings and artefacts until extensive archaeological excavations began in the 18th century. These digs revealed the cities to be rich in erotic artefacts such as statues, frescoes, and household items decorated with sexual themes.

An artifact or artefact is a general term for an item made or given shape by humans, such as a tool or a work of art, especially an object of archaeological interest. In archaeology, the word has become a term of particular nuance and is defined as an object recovered by archaeological endeavor, which may be a cultural artifact having cultural interest.

The Nicholson Museum was an archaeological museum at the University of Sydney home to the Nicholson Collection, the largest collection of antiquities in both Australia and the Southern Hemisphere. Founded in 1860, the collection spans the ancient world with primary collection areas including ancient Egypt, Greece, Italy, Cyprus, and the Near East. The museum closed permanently in February 2020, and the Nicholson Collection is now housed in the Chau Chak Wing Museum at the University of Sydney, open from November 2020. The museum was located in the main quadrangle of the University.

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples is an important Italian archaeological museum, particularly for ancient Roman remains. Its collection includes works from Greek, Roman and Renaissance times, and especially Roman artifacts from the nearby Pompeii, Stabiae and Herculaneum sites. From 1816 to 1861, it was known as Real Museo Borbonico.

I Modi, also known as The Sixteen Pleasures or under the Latin title De omnibus Veneris Schematibus, is a famous erotic book of the Italian Renaissance that had engravings of sexual scenes. The engravings were created in a collaboration between Giulio Romano and Marcantonio Raimondi. They were thought to have been created around 1524 to 1527.

The Secret Museum or Secret Cabinet in Naples is the collection of 1st-century Roman erotic art found in Pompeii and Herculaneum, now held in separate galleries at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, the former Museo Borbonico. The term "cabinet" is used in reference to the "cabinet of curiosities" - i.e. any well-presented collection of objects to admire and study.

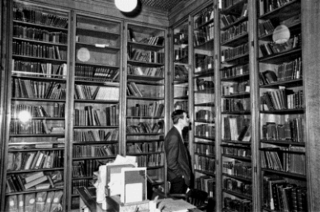

Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks was a British antiquarian and museum administrator. Franks was described by Marjorie Caygill, historian of the British Museum, as "arguably the most important collector in the history of the British Museum, and one of the greatest collectors of his age."

Repatriation is the return of the cultural property, often referring to ancient or looted art, to their country of origin or former owners.

The Department of Asia in the British Museum holds one of the largest collections of historical objects from Asia. These collections comprise over 75,000 objects covering the material culture of the Asian continent, and dating from the Neolithic age up to the present day.

The Oriental Museum, formerly the Gulbenkian Museum of Oriental Art and Archaeology, is a museum of the University of Durham in England. The museum has a collection of more than 23,500 Chinese, Egyptian, Korean, Indian, Japanese and other far east and Asian artefacts. The museum was founded due to the need to house an increasing collection of Oriental artefacts used by the School of Oriental Studies, that were previously housed around the university. The museum's Chinese and Egyptian collections were 'designated' by the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (MLA), now the Arts Council England as being of "national and international importance".

The Museum of Asian Art of Corfu is a museum in the Palace of St. Michael and St. George in Corfu, Greece. The only museum in Greece dedicated to the art of Asia, it has collections of Chinese art, Japanese art, Indian art and others.

In Greek mythology, Priapus is a minor rustic fertility god, protector of livestock, fruit plants, gardens, and male genitalia. Priapus is marked by his oversized, permanent erection, which gave rise to the medical term priapism. He became a popular figure in Roman erotic art and Latin literature, and is the subject of the often humorously obscene collection of verse called the Priapeia.

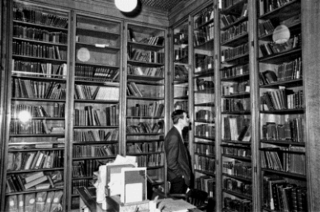

The Private Case is a collection of erotica and pornography held initially by the British Museum and then, from 1973, by the British Library. The collection began between 1836 and 1870 and grew from the receipt of books from legal deposit, from the acquisition of bequests and, in some cases, from requests made to the police following their seizures of obscene material.

Ethnography at the British Museum describes how ethnography has developed at the British Museum.

Gold working in the Bronze Age British Isles refers to the use of gold to produce ornaments and other prestige items in the British Isles during the Bronze Age, between c. 2500 and c. 800 BCE in Britain, and up to about 550 BCE in Ireland. In this period, communities in Britain and Ireland first learned how to work metal, leading to the widespread creation of not only gold but also copper and bronze items as well. Gold artefacts in particular were prestige items used to designate the high status of those individuals who wore, or were buried with them.

George Witt FRS was a medical doctor, banker and mayor known for his collection of erotic objects.