United Empire Loyalist is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the Governor of Quebec and Governor General of the Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North America during or after the American Revolution. At that time, the demonym Canadian or Canadien was used to refer to the indigenous First Nations groups and the descendants of New France settlers inhabiting the Province of Quebec.

Black Canadians, also known as Afro-Canadians, are Canadians of African or Afro-Caribbean descent. The majority of Black Canadians are of Afro-Caribbean and African origin, though the Black Canadian population also consists of African Americans in Canada and their descendants.

The Corps of Colonial Marines were two different British Marine units raised from former black slaves for service in the Americas, at the behest of Alexander Cochrane. The units were created at two separate periods: 1808-1810 during the Napoleonic Wars; and then again during the War of 1812; both units being disbanded once the military threat had passed. Apart from being created in each case by Cochrane, they had no connection with each other.

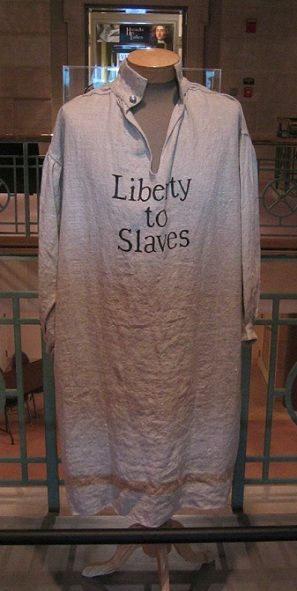

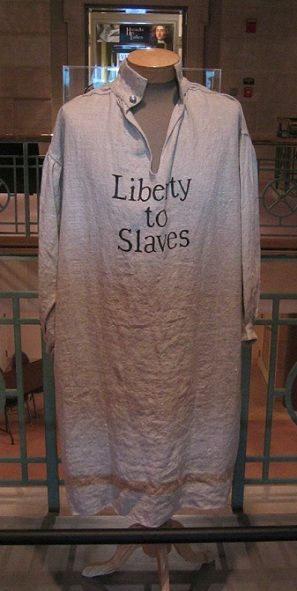

Black Loyalists were African-Americans who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the Crown's guarantee of freedom.

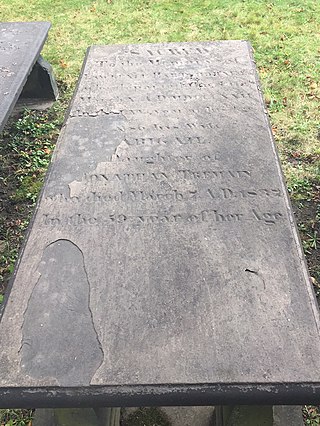

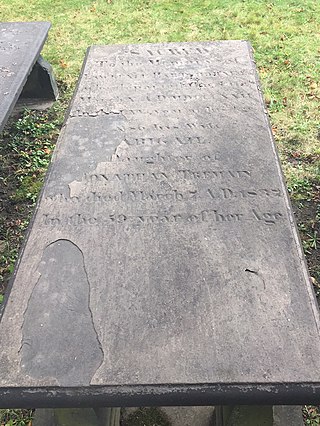

The Old Burying Ground is a historic cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. It is located at the intersection of Barrington Street and Spring Garden Road in Downtown Halifax.

Beechville is a Black Nova Scotian settlement and suburban community within the Halifax Regional Municipality of Nova Scotia, Canada, on St. Margaret's Bay Road. The Beechville Lakeside Timberlea (BLT) trail starts here near Lovett Lake, following the old Halifax and Southwestern Railway line. Ridgecliff Middle School, located in Beechville Estates, serves the communities of Beechville, Lakeside, and Timberlea.

Thomas Peters, born Thomas Potters, was a veteran of the Black Pioneers, fighting for the British in the American Revolutionary War. A Black Loyalist, he was resettled in Nova Scotia, where he became a politician and one of the "Founding Fathers" of the nation of Sierra Leone in West Africa. Peters was among a group of influential Black Canadians who pressed the Crown to fulfill its commitment for land grants in Nova Scotia. Later they recruited African-American settlers in Nova Scotia for the colonisation of Sierra Leone in the late eighteenth century.

By the arrangements of the Canadian federation, the Canadian monarchy operates in Nova Scotia as the core of the province's Westminster-style parliamentary democracy. As such, the Crown within Nova Scotia's jurisdiction is referred to as the Crown in Right of Nova Scotia, His Majesty in Right of Nova Scotia, or the King in Right of Nova Scotia. The Constitution Act, 1867, however, leaves many royal duties in the province specifically assigned to the sovereign's viceroy, the lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia, whose direct participation in governance is limited by the conventional stipulations of constitutional monarchy.

The history of Nova Scotia covers a period from thousands of years ago to the present day. Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day Nova Scotia were inhabited by the Mi'kmaq people. During the first 150 years of European settlement, the region was claimed by France and a colony formed, primarily made up of Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. This time period involved six wars in which the Mi'kmaq along with the French and some Acadians resisted the British invasion of the region: the French and Indian Wars, Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War. During Father Le Loutre's War, the capital was moved from Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, to the newly established Halifax, Nova Scotia (1749). The warfare ended with the Burying the Hatchet ceremony (1761). After the colonial wars, New England Planters and Foreign Protestants immigrated to Nova Scotia. After the American Revolution, Loyalists immigrated to the colony. During the nineteenth century, Nova Scotia became self-governing in 1848 and joined the Canadian Confederation in 1867.

Black Nova Scotians are an ethnic group consisting of Black Canadians whose ancestors primarily date back to the Colonial United States as slaves or freemen, later arriving in Nova Scotia, Canada, during the 18th and early 19th centuries. As of the 2021 Census of Canada, 28,220 Black people live in Nova Scotia, most in Halifax. Since the 1950s, numerous Black Nova Scotians have migrated to Toronto for its larger range of opportunities. The first recorded free African person in Nova Scotia, Mathieu da Costa, a Mikmaq interpreter, was recorded among the founders of Port Royal in 1604. West Africans escaped slavery by coming to Nova Scotia in early British and French Colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries. Many came as enslaved people, primarily from the French West Indies to Nova Scotia during the founding of Louisbourg. The second major migration of people to Nova Scotia happened following the American Revolution, when the British evacuated thousands of slaves who had fled to their lines during the war. They were given freedom by the Crown if they joined British lines, and some 3,000 African Americans were resettled in Nova Scotia after the war, where they were known as Black Loyalists. There was also the forced migration of the Jamaican Maroons in 1796, although the British supported the desire of a third of the Loyalists and nearly all of the Maroons to establish Freetown in Sierra Leone four years later, where they formed the Sierra Leone Creole ethnic identity.

Richard Preston,, was a religious leader and abolitionist. He escaped slavery in Virginia to become an important leader for the African Nova Scotian community and in the international struggle against slavery. He established the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church, the African Abolition Society and the African Baptist Association.

The Book of Negroes is a document created by Brigadier General Samuel Birch, under the direction of Sir Guy Carleton, that records names and descriptions of 3,000 Black Loyalists, enslaved Africans who escaped to the British lines during the American Revolution and were evacuated to points in Nova Scotia as free people of colour.

Moses "Daddy Moses" Wilkinson or "Old Moses" was an American Wesleyan Methodist preacher and Black Loyalist. His ministry combined Old Testament divination with African religious traditions such as conjuring and sorcery. He gained freedom from slavery in Virginia during the American Revolutionary War and was a Wesleyan Methodist preacher in New York and Nova Scotia. In 1791, he migrated to Sierra Leone, preaching alongside ministers Boston King and Henry Beverhout. There, he established the first Methodist church in Settler Town and survived a rebellion in 1800.

The Nova Scotian Settlers, or Sierra Leone Settlers, were African Americans who founded the settlement of Freetown, Sierra Leone and the Colony of Sierra Leone, on March 11, 1792. The majority of these black American immigrants were among 3,000 African Americans, mostly former slaves, who had sought freedom and refuge with the British during the American Revolutionary War, leaving rebel masters. They became known as the Black Loyalists. The Nova Scotian Settlers were jointly led by African American Thomas Peters, a former soldier, and English abolitionist John Clarkson. For most of the 19th century, the Settlers resided in Settler Town and remained a distinct ethnic group within the Freetown territory, tending to marry among themselves and with Europeans in the colony.

Scotch Village is an unincorporated community on the Kennetcook River in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, located in the Municipality of West Hants. This area was part of Newport Township at the time of settlement primarily by Rhode Island Planters in the early 1760s. It was referred to as “Scotchman’s Dyke” or “Scotch Village”, due to settlement of early families of Scottish descent. Prior to the arrival of the Planters, Scotch Village had been the home of Mi'kmaq and Acadians.

This timeline of the history of the Halifax Regional Municipality documents all events that had happened in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, including historical events in the former city of Dartmouth, the Town of Bedford and Halifax County. Events date back to the early 18th century and continue until the present in chronological order.

Upper Hammonds Plains is a Canadian suburban community located in Nova Scotia's Halifax Regional Municipality.

The Merikins or Merikens were African-American Marines of the War of 1812 – former African slaves who fought for the British against the US in the Corps of Colonial Marines and then, after post-war service in Bermuda, were established as a community in the south of Trinidad in 1815–1816. They were settled in an area populated by French-speaking Catholics and retained cohesion as an English-speaking, Baptist community. It is sometimes said that the term "Merikins" derived from the local patois, but as many Americans have long been in the habit of dropping the initial "A" it seems more likely that the new settlers brought that pronunciation with them from the United States. Some of the Company villages and land grants established back then still exist in Trinidad today.

The Province of Nova Scotia was heavily involved in the American Revolutionary War (1776–1783). At that time, Nova Scotia also included present-day New Brunswick until that colony was created in 1784. The Revolution had a significant impact on shaping Nova Scotia, "almost the 14th American Colony". At the beginning, there was ambivalence in Nova Scotia over whether the colony should join the Americans in the war against Britain. Largely as a result of American privateer raids on Nova Scotia villages, as the war continued, the population of Nova Scotia solidified their support for the British. Nova Scotians were also influenced to remain loyal to Britain by the presence of British military units, judicial prosecution by the Nova Scotia Governors and the efforts of Reverend Henry Alline.

American immigration to Canada was a notable part of the social history of Canada. Over Canada's history various refugees and economic migrants from the United States would immigrate to Canada for a variety of reasons. Exiled Loyalists from the United States first came, followed by African-American refugees, economic migrants, and later draft evaders from the Vietnam War.