Related Research Articles

Caesarean section, also known as C-section or caesarean delivery, is the surgical procedure by which one or more babies are delivered through an incision in the mother's abdomen, often performed because vaginal delivery would put the baby or mother at risk. Reasons for the operation include obstructed labor, twin pregnancy, high blood pressure in the mother, breech birth, shoulder presentation, and problems with the placenta or umbilical cord. A caesarean delivery may be performed based upon the shape of the mother's pelvis or history of a previous C-section. A trial of vaginal birth after C-section may be possible. The World Health Organization recommends that caesarean section be performed only when medically necessary.

A multiple birth is the culmination of one multiple pregnancy, wherein the mother gives birth to two or more babies. A term most applicable to vertebrate species, multiple births occur in most kinds of mammals, with varying frequencies. Such births are often named according to the number of offspring, as in twins and triplets. In non-humans, the whole group may also be referred to as a litter, and multiple births may be more common than single births. Multiple births in humans are the exception and can be exceptionally rare in the largest mammals.

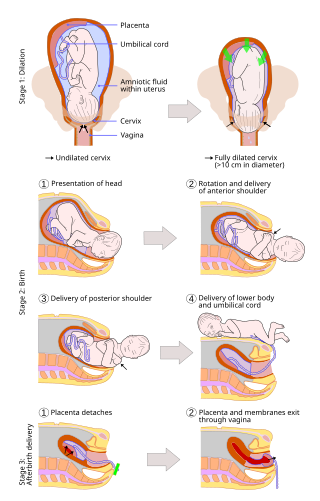

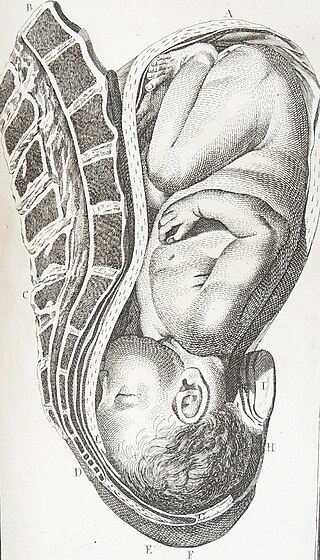

Childbirth, also known as labour, parturition and delivery, is the completion of pregnancy where one or more babies exits the internal environment of the mother via vaginal delivery or caesarean section. In 2019, there were about 140.11 million human births globally. In the developed countries, most deliveries occur in hospitals, while in the developing countries most are home births.

A home birth is a birth that takes place in a residence rather than in a hospital or a birthing center. They may be attended by a midwife, or lay attendant with experience in managing home births. Home birth was, until the advent of modern medicine, the de facto method of delivery. The term was coined in the middle of the 19th century as births began to take place in hospitals.

A breech birth is when a baby is born bottom first instead of head first, as is normal. Around 3–5% of pregnant women at term have a breech baby. Due to their higher than average rate of possible complications for the baby, breech births are generally considered higher risk. Breech births also occur in many other mammals such as dogs and horses, see veterinary obstetrics.

Placenta praevia is when the placenta attaches inside the uterus but in a position near or over the cervical opening. Symptoms include vaginal bleeding in the second half of pregnancy. The bleeding is bright red and tends not to be associated with pain. Complications may include placenta accreta, dangerously low blood pressure, or bleeding after delivery. Complications for the baby may include fetal growth restriction.

Labor induction is the process or treatment that stimulates childbirth and delivery. Inducing (starting) labor can be accomplished with pharmaceutical or non-pharmaceutical methods. In Western countries, it is estimated that one-quarter of pregnant women have their labor medically induced with drug treatment. Inductions are most often performed either with prostaglandin drug treatment alone, or with a combination of prostaglandin and intravenous oxytocin treatment.

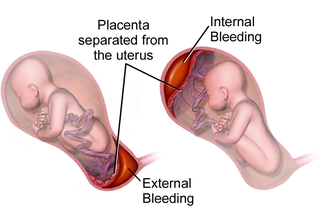

Placental abruption is when the placenta separates early from the uterus, in other words separates before childbirth. It occurs most commonly around 25 weeks of pregnancy. Symptoms may include vaginal bleeding, lower abdominal pain, and dangerously low blood pressure. Complications for the mother can include disseminated intravascular coagulopathy and kidney failure. Complications for the baby can include fetal distress, low birthweight, preterm delivery, and stillbirth.

Complications of pregnancy are health problems that are related to, or arise during pregnancy. Complications that occur primarily during childbirth are termed obstetric labor complications, and problems that occur primarily after childbirth are termed puerperal disorders. While some complications improve or are fully resolved after pregnancy, some may lead to lasting effects, morbidity, or in the most severe cases, maternal or fetal mortality.

Fetal surgery also known as antenatal surgery, prenatal surgery, is a growing branch of maternal-fetal medicine that covers any of a broad range of surgical techniques that are used to treat congenital abnormalities in fetuses who are still in the pregnant uterus. There are three main types: open fetal surgery, which involves completely opening the uterus to operate on the fetus; minimally invasive fetoscopic surgery, which uses small incisions and is guided by fetoscopy and sonography; and percutaneous fetal therapy, which involves placing a catheter under continuous ultrasound guidance.

In case of a previous caesarean section a subsequent pregnancy can be planned beforehand to be delivered by either of the following two main methods:

A vaginal delivery is the birth of offspring in mammals through the vagina. It is the most common method of childbirth worldwide. It is considered the preferred method of delivery, with lower morbidity and mortality than Caesarean sections (C-sections).

An asynclitic birth or asynclitism are terms used in obstetrics to refer to childbirth in which there is malposition of the head of the fetus in the uterus, relative to the birth canal. Asynclitic presentation is different from a shoulder presentation, in which the shoulder is presenting first. Many babies enter the pelvis in an asynclitic presentation, and most asynclitism corrects spontaneously as part of the normal birthing process.

A shoulder presentation is a malpresentation at childbirth where the baby is in a transverse lie, thus the leading part is an arm, a shoulder, or the trunk. While a baby can be delivered vaginally when either the head or the feet/buttocks are the leading part, it usually cannot be expected to be delivered successfully with a shoulder presentation unless a cesarean section (C/S) is performed.

A cephalic presentation or head presentation or head-first presentation is a situation at childbirth where the fetus is in a longitudinal lie and the head enters the pelvis first; the most common form of cephalic presentation is the vertex presentation, where the occiput is the leading part. All other presentations are abnormal (malpresentations) and are either more difficult to deliver or not deliverable by natural means.

Psychiatric disorders of childbirth, as opposed to those of pregnancy or the postpartum period, are psychiatric complications that develop during or immediately following childbirth. Despite modern obstetrics and pain control, these disorders are still observed. Most often, psychiatric disorders of childbirth present as delirium, stupor, rage, acts of desperation, or neonaticide. These psychiatric complications are rarely seen in patients under modern medical supervision. However, care disparities between Europe, North America, Australia, Japan, and other countries with advanced medical care and the rest of the world persist. The wealthiest nations represent 10 million births each year out of the world's total of 135 million. These nations have a maternal mortality rate (MMR) of 6–20/100,000. Poorer nations with high birth rates can have an MMR more than 100 times higher. In Africa, India & South East Asia, as well as Latin America, these complications of parturition may still be as prevalent as they have been throughout human history.

Circumvallate placenta is a rare condition affecting about 1-2% of pregnancies, in which the amnion and chorion fetal membranes essentially "double back" on the fetal side around the edges of the placenta. After delivery, a circumvallate placenta has a thick ring of membranes on its fetal surface. Circumvallate placenta is a placental morphological abnormality associated with increased fetal morbidity and mortality due to the restricted availability of nutrients and oxygen to the developing fetus.

Vaginal seeding, also known as microbirthing, is a procedure whereby vaginal fluids are applied to a new-born child delivered by caesarean section. The idea of vaginal seeding was explored in 2015 after Maria Gloria Dominguez-Bello discovered that birth by caesarean section significantly altered the newborn child's microbiome compared to that of natural birth. The purpose of the technique is to recreate the natural transfer of bacteria that the baby gets during a vaginal birth. It involves placing swabs in the mother's vagina, and then wiping them onto the baby's face, mouth, eyes and skin. Due to the long-drawn nature of studying the impact of vaginal seeding, there are a limited number of studies available that support or refute its use. The evidence suggests that applying microbes from the mother's vaginal canal to the baby after cesarean section may aid in the partial restoration of the infant’s natural gut microbiome with an increased likelihood of pathogenic infection to the child via vertical transmission.

Nicholas M. Fisk is an Australian maternal-fetal medicine specialist, academic and researcher. As an obstetrician, Fisk is known for inventing the natural caesarean operation, also referred to as the family centred caesarean section.

Operative vaginal delivery, also known as assisted or instrumental vaginal delivery, is a vaginal delivery that is assisted by the use of forceps or a vacuum extractor.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 NIH (2006). "State-of-the-Science Conference Statement. Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request". Obstet Gynecol. 107 (6): 1386–97. doi:10.1097/00006250-200606000-00027. PMID 16738168.

- ↑ American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (April 2013). "Cesarean delivery on maternal request". 121 (Committee Opinion No. 559): 904–7.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Finger, C. (2003). "Caesarean section rates skyrocket in Brazil". Lancet. 362 (9384): 628. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14204-3. PMID 12947949. S2CID 54353381.

- ↑ Minkoff, H.; Powderly KP; Chervenak F; McCollough LB (2004). "Ethical dimensions of elective primary cesarean delivery". Obstet Gynecol. 103 (2): 387–92. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000107288.44622.2a. PMID 14754712. S2CID 21783487.

- ↑ Zhang J, Liu Y, Meikle S, Zheng J, Sun W, Li Z (2008). "Cesarean delivery on maternal request in southeast China". Obstet Gynecol. 111 (5): 1077–82. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816e349e. PMID 18448738. S2CID 5914048.

- ↑ Hannah, Mary E. (2 March 2004). "Planned elective cesarean section: A reasonable choice for some women?". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 170 (5): 813–814. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1032002. PMC 343856 . PMID 14993177 . Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ↑ MacKenzie IZ, Cooke I, Annan B (2003). "Indications for Caesarean section in a consultant obstetric unit over three decades". J Obstet Gynaecol. 23 (3): 233–8. doi:10.1080/0144361031000098316. PMID 12850849. S2CID 25452611.

- 1 2 "Elimination of Non-medically Indicated (Elective) Deliveries Before 39 Weeks Gestational Age" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-20. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- ↑ Reddy, Uma M.; Bettegowda, Vani R.; Dias, Todd; Yamada-Kushnir, Tomoko; Ko, Chia-Wen; Willinger, Marian (June 2011). "Term Pregnancy: A Period of Heterogeneous Risk for Infant Mo... : Obstetrics & Gynecology". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 117 (6): 1279–1287. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182179e28. PMC 5485902 . PMID 21606738 . Retrieved 2012-07-12.

- ↑ Cullinane M, Gray A, Hargraves C, Lansdown M, Martin I, Schubert M. "Who operates when? – The 2003 Report of the Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-20. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "La clinica dei record: 9 neonati su 10 nati con il parto cesareo". Corriere della Sera . 14 January 2009. Archived from the original on July 24, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ↑ Wagner, Marsden (November 2006). Born in the USA: How a Broken Maternity System Must Be Fixed to Put Women and Children First . p. 42. ISBN 978-0-520-24596-9.

- ↑ Barley K, Aylin P, Bottle A, Jarman B (2004). "Social class and elective Caesareans in the English NHS". BMJ. 328 (7453): 1399. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7453.1399. PMC 421774 . PMID 15191977.

- ↑ Bewley S, Cockburn J (2002). "The unfacts of 'request' Caesarean section". BJOG. 109 (6): 597–605. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.07106.x. PMID 12118634. S2CID 9702229.

- ↑ Usha Kiran TS, Jayawickrama NS (2002). "Who is responsible for the rising Caesarean section rate?". J Obstet Gynaecol. 22 (4): 363–5. doi:10.1080/01443610220141263. PMID 12521454. S2CID 218854960.

- ↑ Hildingsson I, Rådestad I, Rubertsson C, Waldenström U (2002). "Few women wish to be delivered by Caesarean section". BJOG. 109 (6): 618–23. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01393.x. PMID 12118637. S2CID 24902574.

- 1 2 3 4 Chen, Innie; Opiyo, Newton; Tavender, Emma; Mortazhejri, Sameh; Rader, Tamara; Petkovic, Jennifer; Yogasingam, Sharlini; Taljaard, Monica; Agarwal, Sugandha; Laopaiboon, Malinee; Wasiak, Jason; Khunpradit, Suthit; Lumbiganon, Pisake; Gruen, Russell L.; Betran, Ana Pilar (2018-09-28). "Non-clinical interventions for reducing unnecessary caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD005528. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005528.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6513634 . PMID 30264405.

- ↑ MacDorman, MF; Declercq, E; Menacker, F; Malloy, MH (2006). "Infant and neonatal mortality for primary cesarean and vaginal births to women with "no indicated risk," United States, 1998-2001 birth cohorts". Birth. 33 (3): 175–82. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.513.7283 . doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00102.x. PMID 16948717.

- ↑ Källén, K.; Olausson, PO (2007). "Letter: Neonatal Mortality for Low-Risk Women by Method of Delivery". Birth. 34 (1): 99–100. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00155_1.x. PMID 17324187.

- ↑ Pettker, C.; Funai, E (2007). "Letter: Neonatal Mortality for Low-Risk Women by Method of Delivery". Birth. 34 (1): 100–101. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00155_2.x. PMID 17324188.

- ↑ Roberts, C; Lain, S; Hadfield, R (2007). "Quality of Population Health Data Reporting by Mode of Delivery". Birth. 34 (3): 274–275. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00184_2.x. PMID 17718880.

- ↑ MacDorman, MF; Declercq, E; Menacker, F; Malloy, MH (2008). "Neonatal Mortality for Primary Cesarean and Vaginal Births to Low-Risk Women: Application of an "Intention-to-Treat" Model". Birth. 35 (1): 3–8. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00205.x. PMID 18307481.

- ↑ Liu, Shiliange, Maternal mortality and severe morbidity associated with low-risk planned cesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery at term Canadian Medical Association Journal, February 13, 2007; 176 (4).