Telecommunications in Bolivia includes radio, television, fixed and mobile telephones, and the Internet.

Censorship in South Korea is implemented by various laws that were included in the constitution as well as acts passed by the National Assembly over the decades since 1948. These include the National Security Act, whereby the government may limit the expression of ideas that it perceives "praise or incite the activities of anti-state individuals or groups". Censorship was particularly severe during the country's authoritarian era, with freedom of expression being non-existent, which lasted from 1948 to 1993.

Bolivia's constitution and laws technically guarantee a wide range of human rights, but in practice these rights very often fail to be respected and enforced. “The result of perpetual rights violations by the Bolivian government against its people,” according to the Foundation for Sustainable Development, “has fueled a palpable sense of desperation and anger throughout the country.”

Censorship in India has taken various forms throughout its history. Although the Constitution of India de jure guarantees freedom of expression, de facto there are various certain restrictions on content, with an official view towards "maintaining communal and religious harmony", given the history of communal tension in the nation. According to the Information Technology Rules 2011, objectionable content includes anything that "threatens the unity, integrity, defence, security or sovereignty of India, friendly relations with foreign states or public order".

The mass media in Georgia refers to mass media outlets based in the Republic of Georgia. Television, magazines, and newspapers are all operated by both state-owned and for-profit corporations which depend on advertising, subscription, and other sales-related revenues. The Constitution of Georgia guarantees freedom of speech. Georgia is the only country in its immediate neighborhood where the press is not deemed unfree. As a country in transition, the Georgian media system is under transformation.

Censorship in Turkey is regulated by domestic and international legislation, the latter taking precedence over domestic law, according to Article 90 of the Constitution of Turkey.

Before the independence from the Soviet Union (USSR) in 1990, Lithuanian print media sector served mainly as a propaganda instrument of the Communist Party of Lithuania (LKP). Alternative and uncontrolled press began to appear in the country starting from 1988, when the Initiative Group of the Reform Movement of Lithuania Sąjūdis was established. After the declaration of independence the government stopped interfering in the media outlets which for the most part were first privatised to their journalists and employees and later to local businessman and companies. Currently media ownership in Lithuania is concentrated among a small number of domestic and foreign companies.

Television, magazines, and newspapers have all been operated by both state-owned and for-profit corporations which depend on advertising, subscription, and other sales-related revenues. Even though the Constitution of Russia guarantees freedom of speech, the press has been plagued by both government censorship and self-censorship.

The print, broadcast and online mass media in Burma has undergone strict censorship and regulation since the 1962 Burmese coup d'état. The constitution provides for freedom of speech and the press; however, the government prohibits the exercise of these rights in practice. Reporters Without Borders ranked Burma 174th out of 178 in its 2010 Press Freedom Index, ahead of just Iran, Turkmenistan, North Korea, and Eritrea. In 2015, Burma moved up to 144th place, ahead of many of its ASEAN neighbours such as Singapore, as a result of political changes in the country.

Censorship in Brazil, both cultural and political, occurred throughout the whole period following the colonization of the country. Even though most state censorship ended just before the period of redemocratization that started in 1985, Brazil still experiences a certain amount of non-official censorship today. The current legislation restricts freedom of expression concerning racism and the Constitution prohibits the anonymity of journalists.

Ukraine was in 96th place out of 180 countries listed in the 2020 World Press Freedom Index, having returned to top 100 of this list for the first time since 2009, but dropped down one spot to 97th place in 2021, being characterized as being in a "difficult situation".

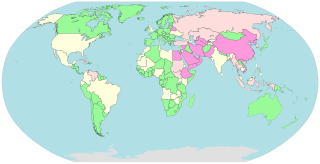

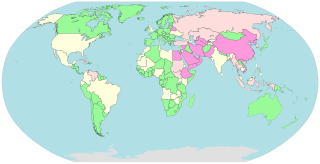

Mass media regulations are a form of media policy with rules enforced by the jurisdiction of law. Guidelines for media use differ across the world. This regulation, via law, rules or procedures, can have various goals, for example intervention to protect a stated "public interest", or encouraging competition and an effective media market, or establishing common technical standards.

Mass media in Zambia consist of several different types of communications media: television, radio, cinema, newspapers, magazines, and Internet-based Web sites. The Ministry of Information, Broadcasting Services and Tourism is in charge of the Zambian News Agency which was founded in 1969. Due to the decolonization of the country, it ultimately allowed the media sector of the country to flourish, and enabled the establishment of multiple different new outlets, as well as established a new news consumption culture that wasn't previously known to Zambia. Furthermore, due to the short-wave capabilities, and international increase in production, demand, and sales of the transistor-radios in the country it made it increasingly more difficult to control the media outlets throughout Zambia by the leaders of the government.

Various television networks, newspapers, and radio stations operate within Rwanda. These forms of mass media serve the Rwandan community by disseminating necessary information among the general public. They are regulated by the self-regulatory body.

Corruption in Bolivia is a major problem that has been called an accepted part of life in the country. It can be found at all levels of Bolivian society. Citizens of the country perceive the judiciary, police and public administration generally as the country's most corrupt. Corruption is also widespread among officials who are supposed to control the illegal drug trade and among those working in and with extractive industries.

Laos has one of the most restrictive media environments in the world. In 2020, Reporters Without Borders ranked Laos 172 out of 179 on its annual Press Freedom Index, behind countries such as Cuba and Iran.

Censorship in Nepal consists of suppression on the expression of political opinion, religious aspect, and obscenity. The Constitution of Nepal guarantees the fundamental rights of citizens, including the freedom of expression. The right to freedom of expression includes the freedom of opinion and thought no matter what a source is. As the Constitution has been developed to push forward democracy, inconsistencies of the Constitution reform create different meanings of prohibiting censorship. The 2004, 2009, and 2015 Constitution are infamous with the restrictions of the rights which are obscure and open for misinterpretation compared to the Constitution announced in 1990.

South Korea is considered to have freedom of the press, but it is subject to several pressures. It has improved since South Korea transitioned to democracy in the late 20th century, but declined slightly in the 2010s. Freedom House Freedom of the Press has classified South Korean press as free from 2002 to 2010, and as partly free since 2011.

Freedoms of expression and of the press are constitutionally guaranteed in Zambia, but the government frequently restricts these rights in practice. Although the ruling Patriotic Front has pledged to free state-owned media—consisting of the Zambia National Broadcasting Corporation (ZNBC) and the widely circulated Zambia Daily Mail and Times of Zambia—from government editorial control, these outlets have generally continued to report along pro-government lines. Many journalists reportedly practice self-censorship since most government newspapers do have prepublication review. The ZNBC dominates the broadcast media, though several private stations have the capacity to reach large portions of the population.

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Africa provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Africa.