China censors both the publishing and viewing of online material. Many controversial events are censored from news coverage, preventing many Chinese citizens from knowing about the actions of their government, and severely restricting freedom of the press. China's censorship includes the complete blockage of various websites, apps, video games, inspiring the policy's nickname, the "Great Firewall of China", which blocks websites. Methods used to block websites and pages include DNS spoofing, blocking access to IP addresses, analyzing and filtering URLs, packet inspection, and resetting connections.

Internet censorship in Australia is enforced by both the country's criminal law as well as voluntarily enacted by internet service providers. The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) has the power to enforce content restrictions on Internet content hosted within Australia, and maintain a blocklist of overseas websites which is then provided for use in filtering software. The restrictions focus primarily on child pornography, sexual violence, and other illegal activities, compiled as a result of a consumer complaints process.

Human rights in South Korea are codified in the Constitution of the Republic of Korea, which compiles the legal rights of its citizens. These rights are protected by the Constitution and include amendments and national referendum. These rights have evolved significantly from the days of military dictatorship to the current state as a constitutional democracy with free and fair elections for the presidency and the members of the National Assembly.

Censorship in Tunisia has been an issue since the country gained independence in 1956. Though considered relatively mild under President Habib Bourguiba (1957–1987), censorship and other forms of repression became common under his successor, President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Ben Ali was listed as one of the "10 Worst Enemies of the Press" by the Committee to Protect Journalists starting in 1998. Reporters Without Borders named Ben Ali as a leading "Predator of Press Freedom". However, the Tunisia Monitoring Group reports that the situation with respect to censorship has improved dramatically since the overthrow of Ben Ali in early 2011.

In Canada, appeals by the judiciary to community standards and the public interest are the ultimate determinants of which forms of expression may legally be published, broadcast, or otherwise publicly disseminated. Other public organisations with the authority to censor include some tribunals and courts under provincial human rights laws, and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, along with self-policing associations of private corporations such as the Canadian Association of Broadcasters and the Canadian Broadcast Standards Council.

Censorship in the People's Republic of China is mandated by the PRC's ruling party, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It is one of the strictest censorship regimes in the world. The government censors content for mainly political reasons, such as curtailing political opposition, and censoring events unfavorable to the CCP, such as the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, pro-democracy movements in China, the persecution of Uyghurs in China, human rights in Tibet, Falun Gong, pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, and aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since Xi Jinping became the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012, censorship has been "significantly stepped up".

Censorship in Myanmar results from government policies in controlling and regulating certain information, particularly on religious, ethnic, political, and moral grounds.

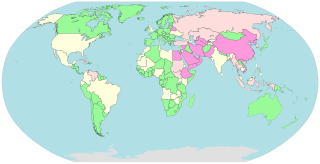

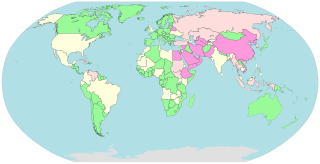

Internet censorship is the legal control or suppression of what can be accessed, published, or viewed on the Internet. Censorship is most often applied to specific internet domains but exceptionally may extend to all Internet resources located outside the jurisdiction of the censoring state. Internet censorship may also put restrictions on what information can be made internet accessible. Organizations providing internet access – such as schools and libraries – may choose to preclude access to material that they consider undesirable, offensive, age-inappropriate or even illegal, and regard this as ethical behavior rather than censorship. Individuals and organizations may engage in self-censorship of material they publish, for moral, religious, or business reasons, to conform to societal norms, political views, due to intimidation, or out of fear of legal or other consequences.

Internet censorship in Morocco was listed as selective in the social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas and as no evidence in the political area by the OpenNet Initiative (ONI) in August 2009. Freedom House listed Morocco's "Internet Freedom Status" as "Partly Free" in its 2018 Freedom on the Net report.

The Internet is accessible to the majority of the population in Egypt, whether via smartphones, internet cafes, or home connections. Broadband Internet access via VDSL is widely available. Under the rule of Hosni Mubarak, Internet censorship and surveillance were severe, culminating in a total shutdown of the Internet in Egypt during the 2011 Revolution. Although Internet access was restored following Mubarak's order, government censorship and surveillance have increased since the 2013 coup d'état, leading the NGO Freedom House to downgrade Egypt's Internet freedom from "partly free" in 2011 to "not free" in 2015, which it has retained in subsequent reports including the most recent in 2021. The el-Sisi regime has ramped up online censorship in Egypt. The regime heavily censors online news websites, which has prompted the closure of many independent news outlets in Egypt.

The print, broadcast and online mass media in Burma has undergone strict censorship and regulation since the 1962 Burmese coup d'état. The constitution provides for freedom of speech and the press; however, the government prohibits the exercise of these rights in practice. Reporters Without Borders ranked Burma 174th out of 178 in its 2010 Press Freedom Index, ahead of just Iran, Turkmenistan, North Korea, and Eritrea. In 2015, Burma moved up to 144th place, ahead of many of its ASEAN neighbours such as Singapore, as a result of political changes in the country.

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments, private institutions, and other controlling bodies.

Freedom of speech is the concept of the inherent human right to voice one's opinion publicly without fear of censorship or punishment. "Speech" is not limited to public speaking and is generally taken to include other forms of expression. The right is preserved in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is granted formal recognition by the laws of most nations. Nonetheless, the degree to which the right is upheld in practice varies greatly from one nation to another. In many nations, particularly those with authoritarian forms of government, overt government censorship is enforced. Censorship has also been claimed to occur in other forms and there are different approaches to issues such as hate speech, obscenity, and defamation laws.

Censorship in Bangladesh refers to the government censorship of the press and infringement of freedom of speech. Article 39 of the constitution of Bangladesh protects free speech.

Internet censorship in South Korea is prevalent, and contains some unique elements such as the blocking of pro-North Korea websites, and to a lesser extent, Japanese websites, which led to it being categorized as "pervasive" in the conflict/security area by OpenNet Initiative. South Korea is also one of the few developed countries where pornography is largely illegal, with the exception of social media websites which are a common source of legal pornography in the country. Any and all material deemed "harmful" or subversive by the state is censored. The country also has a "cyber defamation law", which allow the police to crack down on comments deemed "hateful" without any reports from victims, with citizens being sentenced for such offenses.

There is medium internet censorship in France, including limited filtering of child pornography, laws against websites that promote terrorism or racial hatred, and attempts to protect copyright. The "Freedom on the Net" report by Freedom House has consistently listed France as a country with Internet freedom. Its global ranking was 6 in 2013 and 12 in 2017. A sharp decline in its score, second only to Libya was noted in 2015 and attributed to "problematic policies adopted in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack, such as restrictions on content that could be seen as 'apology for terrorism,' prosecutions of users, and significantly increased surveillance."

The Kingdom of Bahrain is deemed ‘Not Free’ in terms of Net Freedom and Press Freedom by Freedom House. The 2016 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders ranked Bahrain 162nd out of 180 countries.

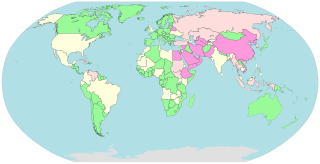

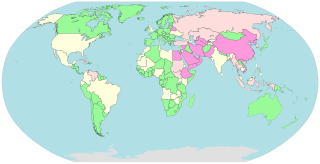

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Asia provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Asia

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in the Americas provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in the Americas.

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Africa provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Africa.