| Part of a series on |

| Censorship by country |

|---|

|

| Countries |

| See also |

Censorship in Poland was first recorded in the 15th century, and it was most notable during the Communist period in the 20th century.

| Part of a series on |

| Censorship by country |

|---|

|

| Countries |

| See also |

Censorship in Poland was first recorded in the 15th century, and it was most notable during the Communist period in the 20th century.

The history of censorship in Poland dates to the late 15th [1] or the first half of the 16th century. [2] The first recorded incident dates to the late 15th century in the Kingdom of Poland related to a complaint by Szwajpolt Fioł (a Franconian from Neustadt living in Krakow) against a Polish bishop who forbade a printer in Kraków from printing liturgical books in Cyrillic script; Fioł lost the case and was sentenced to prison, becoming the first known victim of censorship in Poland. [1] [3] In 1519 sections of the book Chronica Polonorum by Maciej Miechowita, critical of the ruling Jagiellonian dynasty, were censored, making it in turn the first known Polish work to be subject to cuts by censors. [3] A decree of king Zygmunt I Stary of 1523 has been called the first law about censorship in Poland. [4] Together with a series of further edicts by Sigmismund August it prohibited the import and even reading of a number of books related to the Reformation. [1] An edict of Stefan Batory of 1579 in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth introduced the idea of wartime censorship, prohibiting distributing information on military actions. [1] In the 17th century Poland saw the publication and adoption of the first Polish editions of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (1601, 1603, 1617), which among others banned the books of Erasmus of Rotterdam, Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski, Copernicus, Stanisław Sarnicki, Jan Łaski, as well as some other satires (pl:Literatura sowizdrzalska). [1] [4] Extensive internal censorship was also used by the Roman Catholic Church in Poland, as well as by other denominations in Poland, including the Protestant and the Orthodox Churches as well as by the Polish Jews. [4] [5] Outside the religious sphere, several royal decrees from the 17th century explicitly prohibited distribution of several texts, mainly those critical of the royalty; occasional regulations in this matter were also issued by the local municipal governments. [4] [6] [5]

The idea of freedom of speech was in general highly valued by the Polish nobility, [7] [8] and it was one of the key dimensions distinguishing the Commonwealth from the more restrictive absolute monarchies, common in contemporary Europe. [1] Only the banning of books that attacked the Catholic faith was relatively uncontroversial, and attempts to ban other types of works often led to heated debates. [1] [4] [6] In the last century or so of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the issue of censorship was therefore occasionally debated by Polish Sejm and regional sejmiks, usually with regards to individual works or authors, whom some deputies either defended or criticized. There were a number of lawsuits concerning individual books, and some titles were judged and sometimes doomed to be destroyed by burning. [4] [6] Since there was no overall law about the censorship, there were often disputes about jurisdiction in this matter between the bishops, the state officials and the Jagiellonian University. [6] Some country-wide laws related to censorship would be eventually discussed and passed in the Sejm in the last years of the Commonwealth's existence. [4] In particular, the Constitution of May 3, 1791, while it did not address the topics of freedom of press or censorship directly, it guaranteed the freedom of speech in its Article 11 of the "Cardinal and Inviolate Rights". [1] [3]

Following the partitions of Poland, which ended the existence of the independent Polish state in 1795, censorship was in force on the annexed Polish lands, as the codes of occupying states generally contained severe censorship laws. [1] [9] [10] [11] [12] Out of the three regimes, the Russian censorship was the harshest. [3] During some periods, the censorship was so invasive that even the usage of words Poland or Polish was not allowed. [3]

Following Poland regaining independence in 1918, the cabinet of Jędrzej Moraczewski who served as the first Prime Minister of the Second Polish Republic between November 1918 and January 1919 removed preventive censorship, abolishing a number of laws inherited from the partition period, and replacing them with ones more supportive of the freedom of press. New press laws were issued on 7 February 1919, introducing press regulation system and giving the government control over printing houses. [1] In 1920 during the Polish-Soviet war, information about the war was required government's approval. [13] The March Constitution of 1921 confirmed the freedom of speech, and explicitly abolished any preventive censorship and concession system. [1]

Following the May Coup of 1926 censorship targeting opposition press and publications intensified. [13] In practice, Second Polish Republic has been described as having "mild censorship". The censorship was carried by the Ministry of Interior. Printing presses had to provide an advance copy to the Ministry, which could order the publication to be stopped. The publishers were allowed to dispute the Ministry decision in the courts. Newspapers were allowed to indicate that they were subject to censorship by publishing blank spaces. It was common for publishers to skirt the law, for example by delaying the sending of the first copy of a book to the Ministry, which meant that many controversial books were sold in the bookstores before the Ministry censors made their decision. [14] The April Constitution of 1935 did not discuss the freedom of press issue, which has been seen as a step backwards in the issues related to censorship, and a Press Law decree of 1938 introduced a provision which allowed Ministry of Internal Affairs to prevent the distribution of foreign titles. [1] [13] 1939 saw the controversial arrest of a publisher and journalist Stanisław Mackiewicz. [13]

In the Second Polish Republic, censorship was often employed "in defense of decency" against writers whose works were considered "immoral" or "disturbing the social order. [15] Polish historian Ryszard Nycz described the censorship of that time as "focused primarily on anarchists, leftists, and Communist sympathizers among the avant-garde writers". [3] Polish writers whose works were censored included Antoni Słonimski, Julian Tuwim, Józef Łobodowski, Bruno Jasieński, Anatol Stern, Aleksander Wat, Tadeusz Peiper and Marian Czuchnowski . [15] [3] Film censorship (focused on ensuring decency) has been described as extensive, as the law prohibited not only pornographic films but also films showing content that "generally violates codes of morality and law", a formulation that has been used to justify a number of controversial decisions, and according to its critics, made the film censors equal in power to the film directors. The director of the Central Film Bureau within the Ministry of Internal Affairs, colonel Leon Łuskino , has been described as the "terror of the film-makers". [16] [17]

Following the Germany and Soviet occupation of Poland in 1939, the occupying powers once again introduced significant levels of censorship to Polish territories. The Germans prohibited publication of any regular Polish-language book, literary study or scholarly paper. [18] [19]

Censorship at first targeted books that were considered to be "serious", including scientific and educational texts and texts that were thought to promote Polish patriotism; only fiction that was free of anti-German overtones was permitted. Banned literature included maps, atlases and English- and French-language publications, including dictionaries. Several non-public indexes of prohibited books were created, and over 1,500 Polish writers were declared "dangerous to the German state and culture". The index of banned authors included such Polish authors as Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, Stanisław Wyspiański, Bolesław Prus, Stefan Żeromski, Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, Władysław Reymont, Stanisław Wyspiański, Julian Tuwim, Kornel Makuszyński, Leopold Staff, Eliza Orzeszkowa and Maria Konopnicka. Mere possession of such books was illegal and punishable by imprisonment. Door-to-door sale of books was banned, and bookstores—which required a license to operate—were either emptied out or closed. The press was reduced from over 2,000 publications to a few dozen, all censored by the Germans. [20] [21] [22]

Following the communist takeover of Poland, the Main Office of Control of Press, Publications and Performances (Główny Urząd Kontroli Prasy, Publikacji i Widowisk, GUKPiW) was established in the People's Republic of Poland on 5 July 1946 [1] although it traced its origins to the organs established by the provisional Polish communist authorities in 1944. [23] Censorship affected all forms of media: print, television, radio and all kinds of performances. [23] All publications and spectacles had to receive prior approval from GUKPiW, and it also had the right to annul any media publishing or broadcasting licenses. The press laws were subject to major revisions in 1984 and 1989. [1] Communist era censorship targeted topics associated with Soviet repression against Polish citizens, works critical of communism or labeled as subversive, and much of the contemporary émigré literature. [3] As elsewhere in the Soviet Bloc, the censorship was seen as enforcing the party line of the communist party. [24] [23]

The controls were particularly severe during the early years of the communist period (i.e., during the Stalinist era in Poland). [3] During that time, censorship meant not only policing content, as even refusal to print government-endorsed texts could have severe consequences, as evidenced by an incident in 1953 when the weekly Tygodnik Powszechny was temporarily closed and lost its printing house after it refused to print the obituary of Joseph Stalin. [25] [3]

The censorship law was eliminated after the fall of communism in Poland, by the Polish Sejm on 11 April 1990 and the GUKPiW was closed two months later. [26] [27] The closing of the GUKPiW has been described as "the formal and legal fact of lifting censorship [in Poland]" [28] and the year 1990 has been said to have seen the "definite elimination" of censorship in Poland. [23]

The freedom of the press is guaranteed in both the modern Constitution of Poland (1997) and in the revised press law. Another article of the Constitution explicitly prevents preventive censorship, although it does not prohibit post-publishing repressive censorship which in theory might be not incompatible with the modern Polish law. [1]

A plan for Internet censorship legislation that included the creation of a register of blocked web sites was abandoned by the Polish Government in early 2011, following protests and petitions opposing the proposal. [29] [30] [31]

The 2018 amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance has been described by some historians and activists as censorship because it criminalizes statements that allege Polish nation's responsibility for the Holocaust. [32] [33]

On 24 May 2019, Poland filed an action for annulment of the European Union's Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market with the Court of Justice of the European Union. Deputy Foreign Minister of Poland Konrad Szymański said the directive "may result in adopting regulations that are analogous to preventive censorship, which is discouraged not only in the Polish constitution but also in the EU treaties". [34] [35]

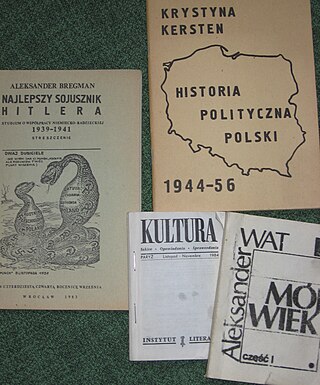

To avoid censorship, throughout the periods that censorship affected the Polish writers, some authors turned to self-censorship, others attempted to cheat the system with metaphors and Aesopian language, and yet others had their works published by the Polish underground press. [23] [3]

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of 312,700 km2 (120,700 sq mi). Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union. Warsaw is the nation's capital and largest metropolis. Other major cities include Kraków, Wrocław, Łódź, Poznań, Gdańsk, and Szczecin.

Stanisław Herman Lem was a Polish writer of science fiction and essays on various subjects, including philosophy, futurology, and literary criticism. Many of his science fiction stories are of satirical and humorous character. Lem's books have been translated into more than 50 languages and have sold more than 45 million copies. Worldwide, he is best known as the author of the 1961 novel Solaris. In 1976 Theodore Sturgeon wrote that Lem was the most widely read science fiction writer in the world.

Polish literature is the literary tradition of Poland. Most Polish literature has been written in the Polish language, though other languages used in Poland over the centuries have also contributed to Polish literary traditions, including Latin, Yiddish, Lithuanian, Russian, German and Esperanto. According to Czesław Miłosz, for centuries Polish literature focused more on drama and poetic self-expression than on fiction. The reasons were manifold but mostly rested on the historical circumstances of the nation. Polish writers typically have had a more profound range of choices to motivate them to write, including past cataclysms of extraordinary violence that swept Poland, but also, Poland's collective incongruities demanding an adequate reaction from the writing communities of any given period.

The Polish People's Republic was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern-day Republic of Poland. From 1947 to 1952 it was known as the Republic of Poland, and it was also often simply known as Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million near the end of its existence, it was the second most-populous communist and Eastern Bloc country in Europe. A unitary state with a Marxist–Leninist government, it was also one of the main signatories of the Warsaw Pact alliance. The largest city and official capital since 1947 was Warsaw, followed by the industrial city of Łódź and cultural city of Kraków. The country was bordered by the Baltic Sea to the north, the Soviet Union to the east, Czechoslovakia to the south, and East Germany to the west.

The Constitution of 3 May 1791, titled the Governance Act, was a constitution adopted by the Great Sejm for the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a dual monarchy comprising the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Constitution was designed to correct the Commonwealth's political flaws. It had been preceded by a period of agitation for—and gradual introduction of—reforms, beginning with the Convocation Sejm of 1764 and the ensuing election that year of Stanisław August Poniatowski, the Commonwealth's last king. It's the second constitution in history, after that of the United States.

Stanisław Kot was a Polish historian and politician. A native of the Austrian partition of Poland, he was attracted to the cause of Polish independence early in life. As a professor of the Jagiellonian University (1920–1933), he held the chair of the History of Culture. His principal expertise was in the politics, ideologies, education, and literature of the 16th- and 17th-century Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He is particularly known for his contributions to the study of the Reformation in Poland.

Martial law in Poland existed between 13 December 1981 and 22 July 1983. The government of the Polish People's Republic drastically restricted everyday life by introducing martial law and a military junta in an attempt to counter political opposition, in particular the Solidarity movement.

The Ministry of Public Security, was the secret police, intelligence and counter-espionage agency operating in the Polish People's Republic. From 1945 to 1954 it was known as the Security Office, and from 1956 to 1990 as the Security Service.

Germany has taken many forms throughout the history of censorship in the country. Various regimes have restricted the press, cinema, literature, and other entertainment venues. In contemporary Germany, the Grundgesetz generally guarantees freedom of press, speech, and opinion.

Religion in Poland is rapidly declining, although historically it had been one of the most Catholic countries in the world.

Polish underground press, devoted to prohibited materials, has a long history of combatting censorship of oppressive regimes in Poland. It existed throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, including under foreign occupation of the country, as well as during the totalitarian rule of the pro-Soviet government. Throughout the Eastern Bloc, bibuła published until the collapse of communism was known also as samizdat.

Law enforcement in Poland consists of the Police (Policja), City Guards, and several smaller specialised agencies. The Prokuratura Krajowa and an independent judiciary also play an important role in the maintenance of law and order.

Human rights in Poland are enumerated in the second chapter of its Constitution, ratified in 1997. Poland is a party to several international agreements relevant to human rights, including the European Convention on Human Rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Helsinki Accords, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Sociology in Poland has been developing, as has sociology throughout Europe, since the mid-19th century. Although, due to the Partitions of Poland, that country did not exist as an independent state in the 19th century or until the end of World War I, some Polish scholars published work clearly belonging to the field of sociology.

Censorship in Communist Poland was primarily performed by the Polish Main Office of Control of Press, Publications and Shows, a governmental institution created in 1946 by the pro-Soviet Provisional Government of National Unity with Stalin's approval and backing, and renamed in 1981 as the Główny Urząd Kontroli Publikacji i Widowisk (GUKPiW). The bureau was liquidated after the fall of communism in Poland, in April 1990.

Book censorship is the act of some authority taking measures to suppress ideas and information within a book. Censorship is "the regulation of free speech and other forms of entrenched authority". Censors typically identify as either a concerned parent, community members who react to a text without reading, or local or national organizations. Books have been censored by authoritarian dictatorships to silence dissent, such as the People's Republic of China, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Books are most often censored for age appropriateness, offensive language, sexual content, amongst other reasons. Similarly, religions may issue lists of banned books, such as the historical example of the Roman Catholic Church's Index Librorum Prohibitorum and bans of such books as Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses by Ayatollah Khomeini, which do not always carry legal force. Censorship can be enacted at the national or subnational level as well, and can carry legal penalties. In many cases, the authors of these books could face harsh sentences, exile from the country, or even execution.

Censorship in Indonesia has varied since the country declared its independence in 1945. For most of its history the government of Indonesia has not fully allowed free speech and has censored controversial, critical, or minority viewpoints, and during periods of crackdown it imprisoned writers and political activists. However, partly due to the weakness of the state and cultural factors, it has never been a country with full censorship where no critical voices were able to be printed or voiced.

Jan Krzysztof Żaryn is a Polish historian, professor and politician, who was a Senator in the Senate of Poland from 2015 to 2019.

Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne is a Polish educational book publisher founded in Warsaw, Poland, in 1945.

The dissident movement in the Polish People's Republic was a political movement in the Polish People's Republic whose aim was to change the political system from unitary Marxist–Leninist government imposed by the USSR to democratic form of government.

Historia cenzury na ziemiach polskich sięga pierwszej połowy XVI w.