Charles Henry Alston was an American painter, sculptor, illustrator, muralist and teacher who lived and worked in the New York City neighborhood of Harlem. Alston was active in the Harlem Renaissance; Alston was the first African-American supervisor for the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project. Alston designed and painted murals at the Harlem Hospital and the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building. In 1990, Alston's bust of Martin Luther King Jr. became the first image of an African American displayed at the White House.

Aaron Douglas was an American painter, illustrator and visual arts educator. He was a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance. He developed his art career painting murals and creating illustrations that addressed social issues around race and segregation in the United States by utilizing African-centric imagery. Douglas set the stage for young, African-American artists to enter the public-arts realm through his involvement with the Harlem Artists Guild. In 1944, he concluded his art career by founding the Art Department at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. He taught visual art classes at Fisk until his retirement in 1966. Douglas is known as a prominent leader in modern African-American art whose work influenced artists for years to come.

Karl Albert Buehr (1866–1952) was a painter born in Germany.

Douglas, on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, is one of Chicago's 77 community areas. The neighborhood is named for Stephen A. Douglas, Illinois politician and Abraham Lincoln's political foe, whose estate included a tract of land given to the federal government. This tract later was developed for use as the Civil War Union training and prison camp, Camp Douglas, located in what is now the eastern portion of the Douglas neighborhood. Douglas gave that part of his estate at Cottage Grove and 35th to the Old University of Chicago. The Chicago 2016 Olympic bid planned for the Olympic Village to be constructed on a 37-acre (15 ha) truck parking lot, south of McCormick Place, that is mostly in the Douglas community area and partly in the Near South Side.

African-American art is a broad term describing visual art created by African Americans. The range of art they have created, and are continuing to create, over more than two centuries is as varied as the artists themselves. Some have drawn on cultural traditions in Africa, and other parts of the world, for inspiration. Others have found inspiration in traditional African-American plastic art forms, including basket weaving, pottery, quilting, woodcarving and painting, all of which are sometimes classified as "handicrafts" or "folk art".

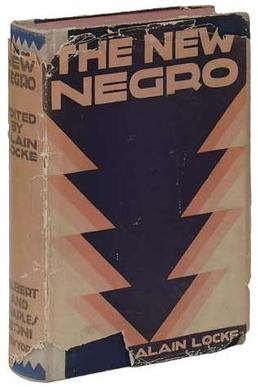

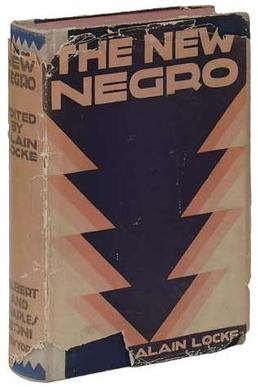

The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925) is an anthology of fiction, poetry, and essays on African and African-American art and literature edited by Alain Locke, who lived in Washington, DC, and taught at Howard University during the Harlem Renaissance. As a collection of the creative efforts coming out of the burgeoning New Negro Movement or Harlem Renaissance, the book is considered by literary scholars and critics to be the definitive text of the movement. "The Negro Renaissance" included Locke's title essay "The New Negro", as well as nonfiction essays, poetry, and fiction by writers including Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, and Eric Walrond.

Winold Reiss was a German-born American artist and graphic designer. He was born in Karlsruhe, Germany. In 1913 he immigrated to the United States, where he was able to follow his interest in Native Americans. In 1920 he went West for the first time, working for a lengthy period on the Blackfeet Reservation. Over the years Reiss painted more than 250 works depicting Native Americans. These paintings by Reiss became known more widely beginning in the 1920 and to the 1950s, when the Great Northern Railway commissioned Reiss to do paintings of the Blackfeet which were then distributed widely as lithographed reproductions on Great Northern calendars.

Laura Wheeler Waring was an American artist and educator, most renowned for her realistic portraits, landscapes, still-life, and well-known African American portraitures she made during the Harlem Renaissance. She was one of the few African American artists in France, a turning point of her career and profession where she attained widespread attention, exhibited in Paris, won awards, and spent the next 30 years teaching art at Cheyney University in Pennsylvania.

Charles Wilbert White, Jr. was an American artist known for his chronicling of African American related subjects in paintings, drawings, lithographs, and murals. White's lifelong commitment to chronicling the triumphs and struggles of his community in representational from, cemented him as one of the most well-known artists in African American art history. Following his death in 1979, White's work has been included in the permanent collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the National Gallery of Art, The Newark Museum, and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. White's best known work is The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy, a mural at Hampton University. In 2018, the centenary year of his birth, the first major retrospective exhibition of his work was organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art.

Palmer C. Hayden was an American painter who depicted African-American life, landscapes, seascapes, and African influences. He sketched, painted in both oils and watercolors, and was a prolific artist of his era.

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement", named after The New Negro, a 1925 anthology edited by Alain Locke. The movement also included the new African American cultural expressions across the urban areas in the Northeast and Midwest United States affected by a renewed militancy in the general struggle for civil rights, combined with the Great Migration of African American workers fleeing the racist conditions of the Jim Crow Deep South, as Harlem was the final destination of the largest number of those who migrated north.

Eldzier Cortor was an African-American artist and printmaker. His work typically features elongated nude figures in intimate settings, influenced by both traditional African art and European surrealism. Cortor is known for his style of realism that makes accurate depictions of poor, Black living conditions look fantastic as he distorts perspective.

Archibald John Motley, Jr., was an American visual artist. Motley is most famous for his colorful chronicling of the African-American experience in Chicago during the 1920s and 1930s, and is considered one of the major contributors to the Harlem Renaissance, or the New Negro Movement, a time in which African-American art reached new heights not just in New York but across America—its local expression is referred to as the Chicago Black Renaissance. He studied painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago during the 1910s, graduating in 1918.

The South Side Community Art Center is a community art center in Chicago that opened in 1940 with support from the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project in Illinois. Opened in Bronzeville in an 1893 mansion, it became the first black art museum in the United States and has been an important center for the development Chicago's African American artists. Of more than 100 community art centers established by the WPA, this is the only one that remains open.

Barkley L. Hendricks was a contemporary American painter who made pioneering contributions to Black portraiture and conceptualism. While he worked in a variety of media and genres throughout his career, Hendricks' best known work took the form of life-sized painted oil portraits of Black Americans.

Walter Ellison (1899–1977) was an African American artist, born in the state of Georgia.

Charles Sebree (1914–1985) was an American painter and playwright best known for his involvement in Chicago's black arts scene of the 1930s and 1940s.

William Thacker McBride Jr. was an African-American artist, designer and collector. McBride began his career in the 1930s in the circles of black art collectives and artistic opportunities afforded by the Works Progress Administration. He would ultimately leave his mark in Chicago as a driving force behind the South Side Community Art Center. McBride distinguished himself as a teacher, as a cultural and political activist, and as a collector of African art and artwork by black artists of his generation.

Valerie Gerrard Browne is an archivist. She has served with many institutions and has focused on collections of women. She is the daughter-in-law of artist Archibald Motley, Jr. (1891–1981) and serves as the caretaker of his legacy.

Susan Cayton Woodson was an American art collector and activist. A central figure in the Chicago Black Renaissance, she was critical in promoting and collecting works by black artists, such as William McBride, Eldzier Cortor, and Charles White.