The Scoville scale is a measurement of pungency of chili peppers and other substances, recorded in Scoville heat units (SHU). It is based on the concentration of capsaicinoids, among which capsaicin is the predominant component.

The bell pepper is the fruit of plants in the Grossum Group of the species Capsicum annuum. Cultivars of the plant produce fruits in different colors, including red, yellow, orange, green, white, chocolate, candy cane striped, and purple. Bell peppers are sometimes grouped with less pungent chili varieties as "sweet peppers". While they are botanically fruits—classified as berries—they are commonly used as a vegetable ingredient or side dish. Other varieties of the genus Capsicum are categorized as chili peppers when they are cultivated for their pungency, including some varieties of Capsicum annuum.

Capsicum pubescens is a plant of the genus Capsicum (pepper). The species name, pubescens, refers to the hairy leaves of this pepper. The hairiness of the leaves, along with the black seeds, make Capsicum pubescens distinguishable from other Capsicum species. Capsicum pubescens has pungent yellow, orange, red, green or brown fruits.

Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum, a chili-pepper variety of Capsicum annuum, is native to southern North America and northern South America. Common names include chiltepín, Indian pepper, grove pepper, chiltepe, and chile tepín, as well as turkey, bird’s eye, or simply bird peppers. Tepín is derived from a Nahuatl word meaning "flea". This variety is the most likely progenitor of the domesticated C. annuum var. annuum. Another similar-sized pepper, 'Pequin' is often confused with tepin, although the tepin fruit is round to oval where as the pequin's fruit is oval with a point, and the leaves, stems and plant structures are very different on each plant.

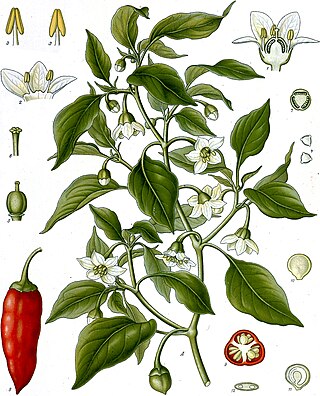

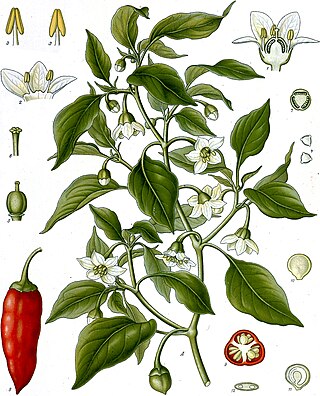

Capsicum annuum is a fruiting plant from the family Solanaceae (nightshades), within the genus Capsicum which is native to the northern regions of South America and to southwestern North America. The plant produces berries of many colors including red, green, and yellow, often with pungent taste. It also has many varieties and common names including paprika, chili pepper, jalapeño, cayenne, bell pepper, and many more with over 200 variations within the species. It is also one of the oldest cultivated crops, with domestication dating back to around 6,000 years ago in regions of Mexico. The genus Capsicum has over 30 species but Capsicum annuum is the primary species in its genus, as it has been widely cultivated for human consumption for a substantial amount of time and has spread across the world. This species has many uses in culinary applications, medicine, self defense, and can even be ornamental.

Capsicum chinense, commonly known as a "habanero-type pepper", is a species of chili pepper native to the Americas. C. chinense varieties are well known for their unique flavors and many have exceptional heat. The hottest peppers in the world are members of this species, with a Scoville Heat Unit score of 2.69 million measured in the C. chinense cultivar, Pepper X in 2023.

The poblano is a mild chili pepper originating in the state of Puebla, Mexico. Dried, it is called ancho or chile ancho, from the Spanish word ancho ("wide"). Stuffed fresh and roasted it is popular in chiles rellenos poblanos.

Capsicum baccatum is a member of the genus Capsicum, and is one of the five domesticated chili pepper species. The fruit tends to be very pungent, and registers 30,000 to 50,000 on the Scoville heat unit scale.

Siling labuyo is a small chili pepper cultivar that developed in the Philippines after the Columbian Exchange. It belongs to the species Capsicum frutescens and is characterized by triangular fruits that grow pointing upwards. The fruits and leaves are used in traditional Philippine cuisine. The fruit is pungent, ranking at 80,000 to 100,000 heat units in the Scoville Scale.

A guajillo chili or guajillo chile or chile guaco or mirasol chile is a landrace variety of the species Capsicum annuum with a mirasol chile fruit type. Mirasol is used to refer to the fresh pepper, and the term guajillo is used for the dry form, which is the second-most common dried chili in Mexican cuisine. The Mexican state of Zacatecas is one of the main producers of guajillo chilies. There are two main varieties that are distinguished by their size and heat factors. The guajillo puya is the smaller and hotter of the two. In contrast, the longer and wider guajillo has a more pronounced, richer flavor and is somewhat less spicy. With a rating of 2,500 to 5,000 on the Scoville scale, its heat is considered mild to medium.

The Fresno chile or Fresno chili pepper is a medium-sized cultivar of Capsicum annuum. It should not be confused with the Fresno Bell pepper. It is often confused with the jalapeño pepper but has thinner walls, often has milder heat, and takes less time to mature. It is, however, a Fresno County chile, which is genetically distinct from the jalapeño and it grows point up, rather than point down as with the jalapeño. The fruit starts out bright green changing to orange and red as fully matured. A mature Fresno pepper will be conical in shape, 50 mm (2 in) long, and about 25 mm (1 in) in diameter at the stem. The plants do well in warm to hot temperatures and dry climates with long sunny summer days and cool nights. They are very cold-sensitive and disease resistant, reaching a height of 60–75 cm (24–30 in).

Guntur Sannam or Capsicum annuum var. longum, is a variety of chili pepper that grows in the districts of Guntur, Prakasam, Warangal (Telangana), and Khammam in India. It is registered as one of the geographical indications of Andhra Pradesh.

The ghost pepper, also known as bhut jolokia, is an interspecific hybrid chili pepper cultivated in Northeast India. It is a hybrid of Capsicum chinense and Capsicum frutescens.

New Mexico chile or New Mexican chile is a cultivar group of the chile pepper from the US state of New Mexico, first grown by Pueblo and Hispano communities throughout Santa Fe de Nuevo México. These landrace chile plants were used to develop the modern New Mexico chile peppers by horticulturist Fabián García and his students, including Roy Nakayama, at what is now New Mexico State University in 1894.

Bird's eye chili or Thai chili is a chili pepper variety from the species Capsicum annuum that is native to Mexico. Cultivated across Southeast Asia, it is used extensively in many Asian cuisines. It may be mistaken for a similar-looking chili derived from the species Capsicum frutescens, the cultivar siling labuyo. Capsicum frutescens fruits are generally smaller and characteristically point upwards.

Capsicum is a genus of flowering plants in the nightshade family Solanaceae, native to the Americas, cultivated worldwide for their chili pepper or bell pepper fruit.

Paprika is a spice made from dried and ground red peppers. It is traditionally made from Capsicum annuum varietals in the Longum group, including chili peppers. Paprika can have varying levels of heat, but the chili peppers used for hot paprika tend to be milder and have thinner flesh than those used to produce chili powder. In some languages, but not English, the word paprika also refers to the plant and the fruit from which the spice is made, as well as to peppers in the Grossum group.

The habanero is a hot variety of chili. Unripe habaneros are green, and they color as they mature. The most common color variants are orange and red, but the fruit may also be white, brown, yellow, green, or purple. Typically, a ripe habanero is 2–6 centimetres long. Habanero chilis are very hot, rated 100,000–350,000 on the Scoville scale. The habanero heat, flavor, and floral aroma make it a common ingredient in hot sauces and other spicy foods.

The fish pepper is a small Chili pepper cultivar of the species Capsicum annuum. It is an heirloom variety developed and preserved by African American communities in the Chesapeake. The plant has variegated foliage and its peppers ripen from white with green streaks to a dark red color. The fish pepper has a wide range of pungency, with Scoville scores from 5,000 to 30,000 units. The pepper was thought to be extinct for the better part of the 20th century until the rediscovery of fifty year-old seeds in an African American family's freezer.