Hades, in the ancient Greek religion and mythology, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although this also made him the last son to be regurgitated by his father. He and his brothers, Zeus and Poseidon, defeated their father's generation of gods, the Titans, and claimed joint rulership over the cosmos. Hades received the underworld, Zeus the sky, and Poseidon the sea, with the solid earth available to all three concurrently. In artistic depictions, Hades is typically portrayed holding a bident and wearing his helm with Cerberus, the three-headed guard-dog of the underworld, standing at his side.

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Persephone, also called Kore or Cora, is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the underworld after her abduction by her uncle Hades, the king of the underworld, who would later also take her into marriage.

Mystery religions, mystery cults, sacred mysteries or simply mysteries, were religious schools of the Greco-Roman world for which participation was reserved to initiates (mystai). The main characterization of this religion is the secrecy associated with the particulars of the initiation and the ritual practice, which may not be revealed to outsiders. The most famous mysteries of Greco-Roman antiquity were the Eleusinian Mysteries, which predated the Greek Dark Ages. The mystery schools flourished in Late Antiquity; Emperor Julian, of the mid 4th century, is believed by some scholars to have been associated with various mystery cults—most notably the mithraists. Due to the secret nature of the school, and because the mystery religions of Late Antiquity were persecuted by the Christian Roman Empire from the 4th century, the details of these religious practices are derived from descriptions, imagery and cross-cultural studies. Much information on the Mysteries comes from Marcus Terentius Varro.

In Greek mythology, Silenus was a companion and tutor to the wine god Dionysus. He is typically older than the satyrs of the Dionysian retinue (thiasos), and sometimes considerably older, in which case he may be referred to as a Papposilenus. Silen and its plural sileni refer to the mythological figure as a type that is sometimes thought to be differentiated from a satyr by having the attributes of a horse rather than a goat, though usage of the two words is not consistent enough to permit a sharp distinction.

The Bacchanalia were unofficial, privately funded popular Roman festivals of Bacchus, based on various ecstatic elements of the Greek Dionysia. They were almost certainly associated with Rome's native cult of Liber, and probably arrived in Rome itself around 200 BC. Like all mystery religions of the ancient world, very little is known of their rites. They seem to have been popular and well-organised throughout the central and southern Italian peninsula.

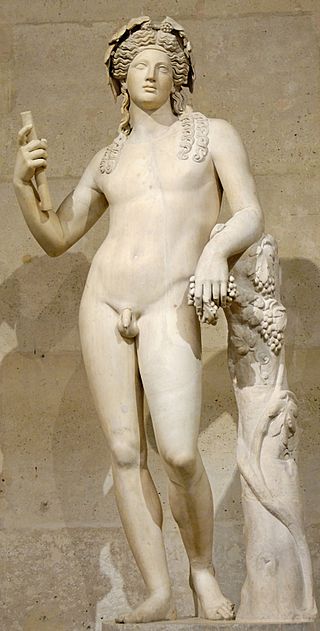

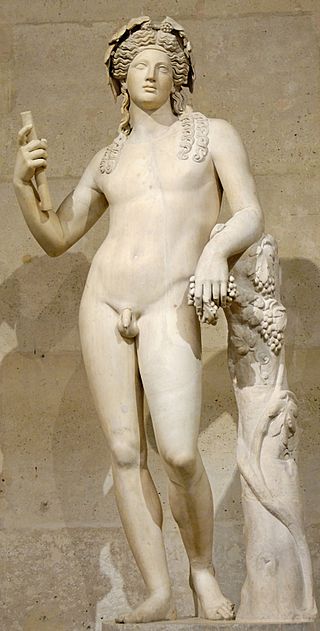

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus is the god of wine-making, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, festivity, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre. He was also known as Bacchus by the Greeks for a frenzy he is said to induce called baccheia. As Dionysus Eleutherius, his wine, music, and ecstatic dance free his followers from self-conscious fear and care, and subvert the oppressive restraints of the powerful. His thyrsus, a fennel-stem sceptre, sometimes wound with ivy and dripping with honey, is both a beneficent wand and a weapon used to destroy those who oppose his cult and the freedoms he represents. Those who partake of his mysteries are believed to become possessed and empowered by the god himself.

Semele, or Thyone in Greek mythology, was the youngest daughter of Cadmus and Harmonia, and the mother of Dionysus by Zeus in one of his many origin myths.

In Greek mythology, maenads were the female followers of Dionysus and the most significant members of the thiasus, the god's retinue. Their name, which comes from μαίνομαι, literally translates as 'raving ones'. Maenads were known as Bassarids, Bacchae, or Bacchantes in Roman mythology after the penchant of the equivalent Roman god, Bacchus, to wear a bassaris or fox skin.

The Bacchae is an ancient Greek tragedy, written by the Athenian playwright Euripides during his final years in Macedonia, at the court of Archelaus I of Macedon. It premiered posthumously at the Theatre of Dionysus in 405 BC as part of a tetralogy that also included Iphigeneia at Aulis and Alcmaeon in Corinth, and which Euripides' son or nephew is assumed to have directed. It won first prize in the City Dionysia festival competition.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Iacchus was a minor deity, of some cultic importance, particularly at Athens and Eleusis in connection with the Eleusinian mysteries, but without any significant mythology. He perhaps originated as the personification of the ritual exclamation Iacche! cried out during the Eleusinian procession from Athens to Eleusis. He was often identified with Dionysus, perhaps because of the resemblance of the names Iacchus and Bacchus, another name for Dionysus. By various accounts he was a son of Demeter, or a son of Persephone, identical with Dionysus Zagreus, or a son of Dionysus.

In Ancient Greece a thyrsus or thyrsos was a wand or staff of giant fennel covered with ivy vines and leaves, sometimes wound with taeniae and topped with a pine cone, artichoke, fennel, or by a bunch of vine-leaves and grapes or ivy-leaves and berries, carried during Hellenic festivals and religious ceremonies. The thyrsus is typically associated with the Greek god Dionysus, and represents a symbol of prosperity, fertility, and hedonism similarly to Dionysus.

Sabazios is the horseman and sky father god of the Phrygians and Thracians. Though the Greeks interpreted Phrygian Sabazios as both Zeus and Dionysus, representations of him, even into Roman times, show him always on horseback, wielding his characteristic staff of power.

The Lenaia was an annual Athenian festival with a dramatic competition. It was one of the lesser festivals of Athens and Ionia in ancient Greece. The Lenaia took place in Athens in Gamelion, roughly corresponding to January. The festival was in honour of Dionysus Lenaios. There is also evidence the festival also took place in Delphi.

Orphism is the name given to a set of religious beliefs and practices originating in the ancient Greek and Hellenistic world, associated with literature ascribed to the mythical poet Orpheus, who descended into the Greek underworld and returned. This type of journey is called a katabasis and is the basis of several hero worships and journeys. Orphics revered Dionysus and Persephone. Orphism has been described as a reform of the earlier Dionysian religion, involving a re-interpretation or re-reading of the myth of Dionysus and a re-ordering of Hesiod's Theogony, based in part on pre-Socratic philosophy.

The Thracian religion comprised the mythology, ritual practices and beliefs of the Thracians, a collection of closely related ancient Indo-European peoples who inhabited eastern and southeastern Europe and northwestern Anatolia throughout antiquity and who included the Thracians proper, the Getae, the Dacians, and the Bithynians. The Thracians themselves did not leave an extensive written corpus of their mythology and rituals, but information about their beliefs is nevertheless available through epigraphic and iconographic sources, as well as through ancient Greek writings.

Omophagia, or omophagy is the eating of raw flesh. The term is of importance in the context of the cult worship of Dionysus.

Sparagmos is an act of rending, tearing apart, or mangling, usually in a Dionysian context.

The cult of Dionysus was strongly associated with satyrs, centaurs, and sileni, and its characteristic symbols were the bull, the serpent, tigers/leopards, ivy, and wine. The Dionysia and Lenaia festivals in Athens were dedicated to Dionysus, as well as the phallic processions. Initiates worshipped him in the Dionysian Mysteries, which were comparable to and linked with the Orphic Mysteries, and may have influenced Gnosticism. Orpheus was said to have invented the Mysteries of Dionysus.

In ancient Greek religion, an orgion was an ecstatic form of worship characteristic of some mystery cults. The orgion is in particular a cult ceremony of Dionysos, celebrated widely in Arcadia, featuring "unrestrained" masked dances by torchlight and animal sacrifice by means of random slashing that evoked the god's own rending and suffering at the hands of the Titans. The orgia that explained the role of the Titans in Dionysos's dismemberment were said to have been composed by Onomacritus. Greek art and literature, as well as some patristic texts, indicate that the orgia involved snake handling.

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Eubuleus is a god known primarily from devotional inscriptions for mystery religions. The name appears several times in the corpus of the so-called Orphic gold tablets spelled variously, with forms including Euboulos, Eubouleos and Eubolos. It may be an epithet of the central Orphic god, Dionysus or Zagreus, or of Zeus in an unusual association with the Eleusinian Mysteries. Scholars of the late 20th and early 21st centuries have begun to consider Eubuleus independently as "a major god" of the mysteries, based on his prominence in the inscriptional evidence. His depiction in art as a torchbearer suggests that his role was to lead the way back from the Underworld.