Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structuring society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.

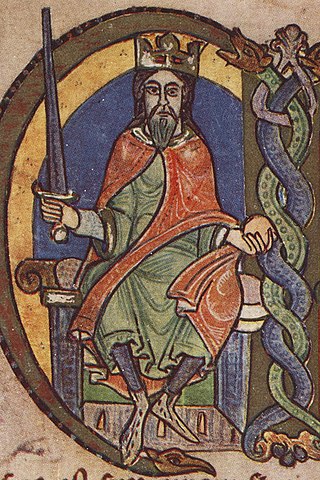

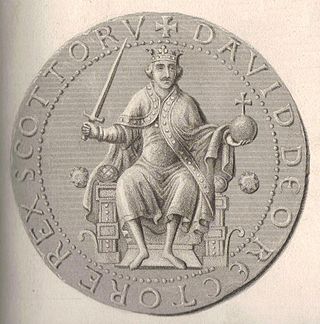

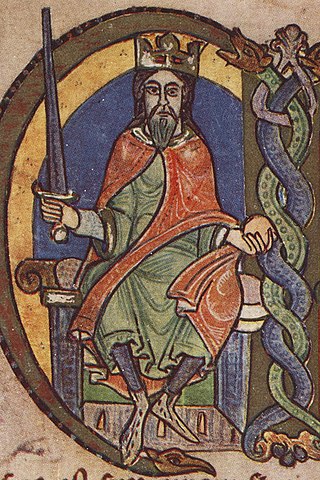

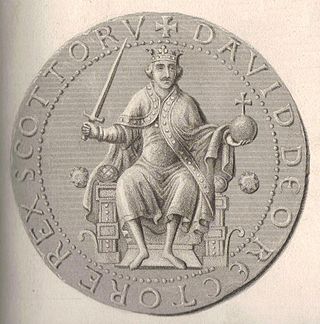

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Malcolm III and Margaret of Wessex, David spent most of his childhood in Scotland, but was exiled to England temporarily in 1093. Perhaps after 1100, he became a dependent at the court of King Henry I. There he was influenced by the Anglo-French culture of the court.

Whithorn, Taigh Mhàrtainn in modern Gaelic), is a royal burgh in the historic county of Wigtownshire in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, about 10 miles (16 km) south of Wigtown. The town was the location of the first recorded Christian church in Scotland, Candida Casa 'White/Shining House', built by Saint Ninian about 397.

The Bishop of Galloway, also called the Bishop of Whithorn, was the eccesiastical head of the Diocese of Galloway, said to have been founded by Saint Ninian in the mid-5th century. The subsequent Anglo-Saxon bishopric was founded in the late 7th century or early 8th century, and the first known bishop was one Pehthelm, "shield of the Picts". According to Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical tradition, the bishopric was founded by Saint Ninian, a later corruption of the British name Uinniau or Irish Finian; although there is no contemporary evidence, it is quite likely that there had been a British or Hiberno-British bishopric before the Anglo-Saxon takeover. After Heathored, no bishop is known until the apparent resurrection of the diocese in the reign of King Fergus of Galloway. The bishops remained, uniquely for Scottish bishops, the suffragans of the Archbishop of York until 1359 when the pope released the bishopric from requiring metropolitan assent. James I formalised the admission of the diocese into the Scottish church on 26 August 1430 and just as all Scottish sees, Whithorn was to be accountable directly to the pope. The diocese was placed under the metropolitan jurisdiction of St Andrews on 17 August 1472 and then moved to the province of Glasgow on 9 January 1492. The diocese disappeared during the Scottish Reformation, but was recreated by the Catholic Church in 1878 with its cathedra at Dumfries, although it is now based at Ayr.

Fergus of Galloway was a twelfth-century Lord of Galloway. Although his familial origins are unknown, it is possible that he was of Norse-Gaelic ancestry. Fergus first appears on record in 1136, when he witnessed a charter of David I, King of Scotland. There is considerable evidence indicating that Fergus was married to an illegitimate daughter of Henry I, King of England. It is possible that Elizabeth Fitzroy was the mother of Fergus's three children.

Donnchadh was a Gall-Gaidhil prince and Scottish magnate in what is now south-western Scotland, whose career stretched from the last quarter of the 12th century until his death in 1250. His father, Gille-Brighde of Galloway, and his uncle, Uhtred of Galloway, were the two rival sons of Fergus, Prince or Lord of Galloway. As a result of Gille-Brighde's conflict with Uhtred and the Scottish monarch William the Lion, Donnchadh became a hostage of King Henry II of England. He probably remained in England for almost a decade before returning north on the death of his father. Although denied succession to all the lands of Galloway, he was granted lordship over Carrick in the north.

Christianity in Medieval Scotland includes all aspects of Christianity in the modern borders of Scotland in the Middle Ages. Christianity was probably introduced to what is now Lowland Scotland by Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of Britannia. After the collapse of Roman authority in the fifth century, Christianity is presumed to have survived among the British enclaves in the south of what is now Scotland, but retreated as the pagan Anglo-Saxons advanced. Scotland was largely converted by Irish missions associated with figures such as St Columba, from the fifth to the seventh centuries. These missions founded monastic institutions and collegiate churches that served large areas. Scholars have identified a distinctive form of Celtic Christianity, in which abbots were more significant than bishops, attitudes to clerical celibacy were more relaxed and there were significant differences in practice with Roman Christianity, particularly the form of tonsure and the method of calculating Easter, although most of these issues had been resolved by the mid-seventh century. After the reconversion of Scandinavian Scotland in the tenth century, Christianity under papal authority was the dominant religion of the kingdom.

The High Middle Ages of Scotland encompass Scotland in the era between the death of Domnall II in 900 AD and the death of King Alexander III in 1286, which was an indirect cause of the Wars of Scottish Independence.

Before David I became the King of Scotland in 1124, he was the prince of the Cumbrians and earl of a great territory in the middle of England acquired by marriage. This period marks the beginning of his life as a great territorial lord. Circa 1113, the year in which King Henry I of England arranged his marriage to an English heiress and the year in which for the first time David can be found in possession of "Scottish" territory, marks the beginning of his rise to Scottish leadership.

Political and military events in Scotland during the reign of David I are the events which took place in Scotland during David I of Scotland's reign as King of Scots, from 1124 to 1153. When his brother Alexander I of Scotland died in 1124, David chose, with the backing of Henry I of England, to take the Kingdom of Alba for himself. David was forced to engage in warfare against his rival and nephew, Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair. Subduing the latter took David ten years, and involved the destruction of Óengus, mormaer of Moray. David's victory allowed him to expand his control over more distant regions theoretically part of the Kingdom. In this he was largely successful, although he failed to bring the Earldom of Orkney into his kingdom.

The Davidian Revolution is a name given by many scholars to the changes which took place in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of David I (1124–1153). These included his foundation of burghs, implementation of the ideals of Gregorian Reform, foundation of monasteries, Normanisation of the Scottish government, and the introduction of feudalism through immigrant Norman and Anglo-Norman knights.

Historical treatment of David I and the Scottish church usually emphasises King David I of Scotland's pioneering role as the instrument of diocesan reorganisation and Norman penetration, beginning with the bishopric of Glasgow while David was Prince of the Cumbrians, and continuing further north after David acceded to the throne of Scotland. As well as this and his monastic patronage, focus too is usually given to his role as the defender of the Scottish church's independence from claims of overlordship by the Archbishop of York and the Archbishop of Canterbury.

George Vaus was a Scottish prelate of the late 15th and early 16th century.

The economic history of Scotland charts economic development in the history of Scotland from earliest times, through seven centuries as an independent state and following Union with England, three centuries as a country of the United Kingdom. Before 1700 Scotland was a poor rural area, with few natural resources or advantages, remotely located on the periphery of the European world. Outward migration to England, and to North America, was heavy from 1700 well into the 20th century. After 1800 the economy took off, and industrialized rapidly, with textile, coal, iron, railroads, and most famously shipbuilding and banking. Glasgow was the centre of the Scottish economy. After the end of the First World War in 1918, Scotland went into a steady economic decline, shedding thousands of high-paying engineering jobs, and having very high rates of unemployment especially in the 1930s. Wartime demand in the Second World War temporarily reversed the decline, but conditions were difficult in the 1950s and 1960s. The discovery of North Sea oil in the 1970s brought new wealth, and a new cycle of boom and bust, even as the old industrial base had decayed.

Georgian feudalism, or patronkmoba, as the system of personal dependence or vassalage in ancient and medieval Georgia is referred to, arose from a tribal-dynastic organization of society upon which was imposed, by royal authority, an official hierarchy of regional governors, local officials and subordinates. It is thought to have its roots into the ancient Georgian, or Iberian, society of Hellenistic period.

Scotland in the Late Middle Ages, between the deaths of Alexander III in 1286 and James IV in 1513, established its independence from England under figures including William Wallace in the late 13th century and Robert Bruce in the 14th century. In the 15th century under the Stewart Dynasty, despite a turbulent political history, the Crown gained greater political control at the expense of independent lords and regained most of its lost territory to approximately the modern borders of the country. However, the Auld Alliance with France led to the heavy defeat of a Scottish army at the Battle of Flodden in 1513 and the death of the king James IV, which would be followed by a long minority and a period of political instability.

Feudalism as practiced in the Kingdoms of England during the medieval period was a state of human society that organized political and military leadership and force around a stratified formal structure based on land tenure. As a military defence and socio-economic paradigm designed to direct the wealth of the land to the king while it levied military troops to his causes, feudal society was ordered around relationships derived from the holding of land. Such landholdings are termed fiefdoms, traders, fiefs, or fees.

Scottish society in the Middle Ages is the social organisation of what is now Scotland between the departure of the Romans from Britain in the fifth century and the establishment of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. Social structure is obscure in the early part of the period, for which there are few documentary sources. Kinship groups probably provided the primary system of organisation and society was probably divided between a small aristocracy, whose rationale was based around warfare, a wider group of freemen, who had the right to bear arms and were represented in law codes, above a relatively large body of slaves, who may have lived beside and become clients of their owners.

The economy of Scotland in the Middle Ages covers all forms of economic activity in the modern boundaries of Scotland, between the End of Roman rule in Britain in the early fifth century, until the advent of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century, including agriculture, crafts and trade. Having between a fifth or sixth (15-20 %) of the arable or good pastoral land and roughly the same amount of coastline as England and Wales, marginal pastoral agriculture and fishing were two of the most important aspects of the Medieval Scottish economy. With poor communications, in the early Middle Ages most settlements needed to achieve a degree of self-sufficiency in agriculture. Most farms were operated by a family unit and used an infield and outfield system.

Agriculture in Scotland in the Middle Ages includes all forms of farm production in the modern boundaries of Scotland, between the departure of the Romans from Britain in the fifth century and the establishment of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. Scotland has between a fifth and a sixth of the amount of the arable or good pastoral land of England and Wales, mostly located in the south and east. Heavy rainfall encouraged the spread of acidic blanket peat bog, which with wind and salt spray, made most of the western islands treeless. The existence of hills, mountains, quicksands and marshes made internal communication and agriculture difficult. Most farms had to produce a self-sufficient diet of meat, dairy products and cereals, supplemented by hunter-gathering. The early Middle Ages were a period of climate deterioration resulting in more land becoming unproductive. Farming was based around a single homestead or a small cluster of three or four homes, each probably containing a nuclear family and cattle were the most important domesticated animal.