Aberdare is a town in the Cynon Valley area of Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wales, at the confluence of the Rivers Dare (Dâr) and Cynon. Aberdare has a population of 39,550. Aberdare is 4 miles (6 km) south-west of Merthyr Tydfil, 20 miles (32 km) north-west of Cardiff and 22 miles (35 km) east-north-east of Swansea. During the 19th century it became a thriving industrial settlement, which was also notable for the vitality of its cultural life and as an important publishing centre.

Glamorgan, or sometimes Glamorganshire, is one of the thirteen historic counties of Wales and a former administrative county of Wales. Originally an early medieval petty kingdom of varying boundaries known in Welsh as the Kingdom of Morgannwg, which was then invaded and taken over by the Normans as the Lordship of Glamorgan. The area that became known as Glamorgan was both a rural, pastoral area, and a conflict point between the Norman lords and the Welsh princes. It was defined by a large concentration of castles.

Pontypool is a town and the administrative centre of the county borough of Torfaen, within the historic boundaries of Monmouthshire in South Wales. It has a population of 28,970.

Glanamman is a Welsh mining village in the valley of the River Amman in Carmarthenshire. Glanamman has long been a stronghold of the Welsh language; village life is largely conducted in Welsh. Like the neighbouring village of Garnant it experienced a coal-mining boom in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but the last big colliery closed in 1947 and coal has been extracted fitfully since then.

Gorseinon is a town within the City and County of Swansea, Wales, near the Loughor estuary. It was a small village until the late 19th century when it grew around the coal mining and tinplate industries. It is situated in the north west of Swansea City Centre, around 6 miles (10 km) north west of the city centre. Gorseinon is a local government community with an elected town council.

Pontardawe is a town and a community in the Swansea Valley in Wales. With a population of 6,832 in 2011, it comprises the electoral wards of Pontardawe and Trebanos. A town council is elected. Pontardawe forms part of the county borough of Neath Port Talbot. On the opposite bank of the River Tawe, the village of Alltwen, part of the community of Cilybebyll, is administered separately from Pontardawe. Pontardawe is at the crossroads of the A474 road and the A4067 road. Pontardawe came into existence as a small settlement on the northwestern bank of the Tawe where the drovers' road from Neath and Llandeilo crossed the river to go up the valley to Brecon.

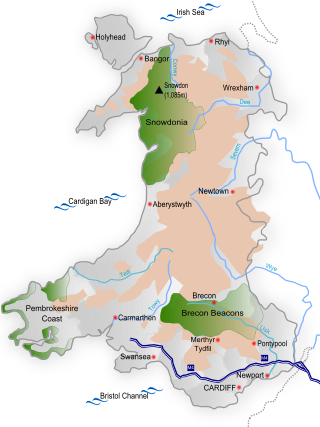

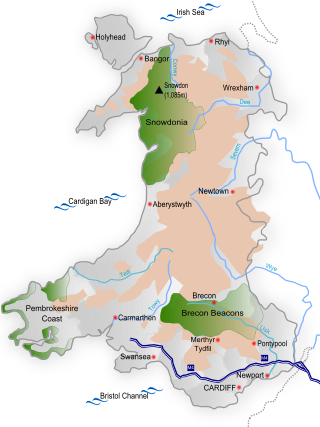

South Wales is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards to include Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire. In the western extent, from Swansea westwards, local people would probably recognise that they lived in both south Wales and west Wales. The Brecon Beacons National Park covers about a third of south Wales, containing Pen y Fan, the highest British mountain south of Cadair Idris in Snowdonia.

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and whose physical geography is characterised by a varied coastline and a largely upland interior. It is bordered by England to its east, the Irish Sea to its north and west, and the Bristol Channel to its south. It has a total area of 2,064,100 hectares and is about 170 mi (274 km) from north to south and at least 60 mi (97 km) wide. It comprises 8.35 percent of the land of the United Kingdom. It has a number of offshore islands, by far the largest of which is Anglesey. The mainland coastline, including Anglesey, is about 1,680 mi (2,704 km) in length. As of 2014, Wales had a population of about 3,092,000; Cardiff is the capital and largest city and is situated in the urbanised area of South East Wales.

The South Wales Valleys are a group of industrialised peri-urban valleys in South Wales. Most of the valleys run north–south, roughly parallel to each other. Commonly referred to as "The Valleys", they stretch from Carmarthenshire in the west to Monmouthshire in the east; to the edge of the pastoral country of the Vale of Glamorgan and the coastal plain near the cities of Swansea, Cardiff, and Newport.

The history of Swansea in South Wales covers a period of continuous occupation stretching back a thousand years, while there is archaeological evidence of prehistoric human occupation of the surrounding area for thousands of years before that.

The economy of Wales is part of the wider economy of the United Kingdom, and encompasses the production and consumption of goods, services and the supply of money in Wales.

The South Wales Coalfield extends across Pembrokeshire, Carmarthenshire, Swansea, Neath Port Talbot, Bridgend, Rhondda Cynon Taf, Merthyr Tydfil, Caerphilly, Blaenau Gwent and Torfaen. It is rich in coal deposits, especially in the South Wales Valleys.

Cwmdare is a village very close to Aberdare, in Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wales. The village's history is intertwined with coal-mining, and since the decline of the industry in the 1980s, it has become primarily a commuter base for the larger surrounding towns of Aberdare and Merthyr Tydfil and Pontypridd, as well as the cities of Cardiff and Swansea.

The Lower Swansea valley is the lower half of the valley of the River Tawe in south Wales. It runs from approximately the level of Clydach down to Swansea docks, where it opens into Swansea Bay and the Bristol Channel. This relatively small area was a focus of industrial innovation and invention during the Industrial Revolution, leading to a transformation of the landscape and a rapid rise in the population and economy of Swansea.

The City and County of Swansea is an urban centre with a largely rural hinterland in Gower; the city has been described as the regional centre for South West Wales. Swansea's travel to work area, not coterminous with the local authority, also contained the Swansea Valley in 1991; the new 2001-based version merges the Swansea, Neath & Port Talbot, and Llanelli areas into a new Swansea Bay travel to work area. Formerly an industrial centre, most employment in the city is now in the service sector.

Mining in Wales provided a significant source of income to the economy of Wales throughout the nineteenth century and early twentieth century. It was key to the Industrial Revolution in Wales.

The coal industry in Wales played an important role in the Industrial Revolution in Wales. Coal mining in Wales expanded in the 18th century to provide fuel for the blast furnaces of the iron and copper industries that were expanding in southern Wales. The industry had reached large proportions by the end of that century, and then further expanded to supply steam-coal for the steam vessels that were beginning to trade around the world. The Cardiff Coal Exchange set the world price for steam-coal and Cardiff became a major coal-exporting port. The South Wales Coalfield was at its peak in 1913 and was one of the largest coalfields in the world. It remained the largest coalfield in Britain until 1925. The supply of coal dwindled, and pits closed in spite of a UK-wide strike against closures. Aberpergwm Colliery is the last deep mine in Wales.

The industrial revolution in Wales was the adoption and developments of new technologies in Wales in the 18th and 19th centuries, resulting in increases in the scale of industry in Wales, as part of the wider Industrial Revolution.