Storyville was the red-light district of New Orleans, Louisiana, from 1897 to 1917. It was established by municipal ordinance under the New Orleans City Council, to regulate prostitution. Sidney Story, a city alderman, wrote guidelines and legislation to control prostitution within the city. The ordinance designated an area of the city in which prostitution, although still nominally illegal, was tolerated or regulated. The area was originally referred to as "The District", but its nickname, "Storyville", soon caught on, much to the chagrin of Alderman Story. It was bound by the streets of North Robertson, Iberville, Basin, and St. Louis Streets. It was located by a train station, making it a popular destination for travelers throughout the city, and became a centralized attraction in the heart of New Orleans. Only a few of its remnants are now visible. The neighborhood lies in Faubourg Tremé and the majority of the land was repurposed for public housing. It is well known for being the home of jazz musicians, most notably Louis Armstrong as a minor.

Nevada is the only U.S. state where prostitution is legally permitted in some form. Prostitution is legal in 10 of Nevada's 17 counties, although only six allow it in every municipality. Six counties have at least one active brothel, which mainly operate in isolated, rural areas. The state's most populated counties, Clark and Washoe, are among those that do not permit prostitution. It is also illegal in Nevada's capital, Carson City, an independent city.

A brothel, bordello, ranch, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in sexual activity with prostitutes. However, for legal or cultural reasons, establishments often describe themselves as massage parlors, bars, strip clubs, body rub parlours, studios, or by some other description. Sex work in a brothel is considered safer than street prostitution.

Betty Jean O'Hara was a famed prostitute in Honolulu's "vice district" during World War II.

Prostitution in Germany is legal, as are other aspects of the sex industry, including brothels, advertisement, and job offers through HR companies. Full-service sex work is widespread and regulated by the German government, which levies taxes on it. In 2016, the government adopted a new law, the Prostitutes Protection Act, in an effort to improve the legal situation of sex workers, while also now enacting a legal requirement for registration of prostitution activity and banning prostitution which involves no use of condoms. The social stigmatization of sex work persists and many workers continue to lead a double life. Human rights organizations consider the resulting common exploitation of women from East Germany to be the main problem associated with the profession.

Prostitution in the Netherlands is legal and regulated. Operating a brothel is also legal. De Wallen, the largest and best-known Red-light district in Amsterdam, is a destination for international sex tourism.

Baltimore's The Block is a stretch on the 400 block of East Baltimore Street in Baltimore, Maryland, containing several strip clubs, sex shops, and other adult entertainment merchants. During the 19th century, Baltimore was filled with brothels, and in the first half of the 20th century, it was famous for its burlesque houses. It was a noted starting point and stop-over for many noted burlesque dancers, including the likes of Blaze Starr.

The Levee District was the red-light district of Chicago from the 1880s until 1912, when police raids shut it down. The district, like many frontier town red-light districts, got its name from its proximity to wharves in the city. The Levee district encompassed four blocks in Chicago's South Loop area, between 18th and 22nd streets. It was home to many brothels, saloons, dance halls, and the famed Everleigh Club. Prostitution boomed in the Levee District, and it was not until the Chicago Vice Commission submitted a report on the city's vice districts that it was shut down.

Prostitution is illegal in the vast majority of the United States as a result of state laws rather than federal laws. It is, however, legal in some rural counties within the state of Nevada. Additionally, it is decriminalized to sell sex in the state of Maine, but illegal to buy sex. Prostitution nevertheless occurs elsewhere in the country.

Prostitution in Ireland is legal. However, since March 2017, it has been an offence to buy sex. All forms of third party involvement are illegal but are commonly practiced. Since the law that criminalises clients came into being, with the purpose of reducing the demand for prostitution, the number of prosecutions for the purchase of sex increased from 10 in 2018 to 92 in 2020. In a report from UCD's Sexual Exploitation Research Programme the development is called ”a promising start in interrupting the demand for prostitution.” Most prostitution in Ireland occurs indoors. Street prostitution has declined considerably in the 21st century, with the vast majority of prostitution now advertised on the internet.

Procuring, pimping, or pandering is the facilitation or provision of a prostitute or other sex worker in the arrangement of a sex act with a customer. A procurer, colloquially called a pimp or a madam or a brothel keeper, is an agent for prostitutes who collects part of their earnings. The procurer may receive this money in return for advertising services, physical protection, or for providing and possibly monopolizing a location where the prostitute may solicit clients. Like prostitution, the legality of certain actions of a madam or a pimp vary from one region to the next.

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact with the customer. The requirement of physical contact also creates the risk of transferring infections. Prostitution is sometimes described as sexual services, commercial sex or, colloquially, hooking. It is sometimes referred to euphemistically as "the world's oldest profession" in the English-speaking world. A person who works in this field is called a prostitute, and sometimes a sex worker, but some other words, such as hooker, putana, or whore are also sometimes used to refer to those who work as prostitutes.

Prostitution in Vietnam is illegal and considered a serious crime. Nonetheless, Vietnam's Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA) has estimated that there were 71,936 prostitutes in the country in 2013. Other estimates puts the number at up to 200,000.

Prostitution in Trinidad and Tobago is legal but related activities such as brothel keeping, soliciting and pimping are illegal.

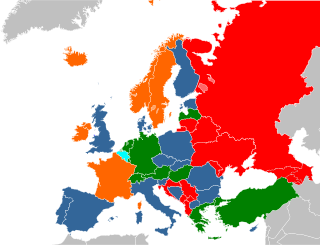

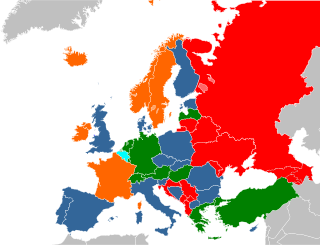

The legality of prostitution in Europe varies by country.

Prostitution has been practiced throughout ancient and modern cultures. Prostitution has been described as "the world's oldest profession"..

The history of prostitution in Canada is based on the fact that Canada inherited its criminal laws from England. The first recorded laws dealing with prostitution were in Nova Scotia in 1759, although as early as August 19, 1675 the Sovereign Council of New France convicted Catherine Guichelin, one of the King's Daughters, with leading a "life scandalous and dishonest to the public", declared her a prostitute and banished her from the walls of Quebec City under threat of the whip. Following Canadian Confederation, the laws were consolidated in the Criminal Code. These dealt principally with pimping, procuring, operating brothels and soliciting. Most amendments to date have dealt with the latter, originally classified as a vagrancy offence, this was amended to soliciting in 1972, and communicating in 1985. Since the Charter of Rights and Freedoms became law, the constitutionality of Canada's prostitution laws have been challenged on a number of occasions.

Controlling Vice: Regulating Brothel Prostitution in St. Paul, 1865–1883 is a book by Minnesotan author Joel Best, published in 1998. It is the fourth book in the History of Crime and Criminal Justice Series, and documents the strategies that the Minnesota police officers enforced in attempts to regulate prostitution in the late nineteenth century.

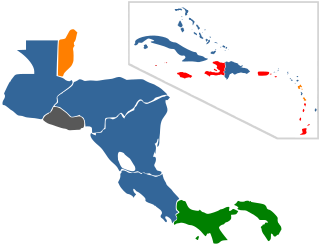

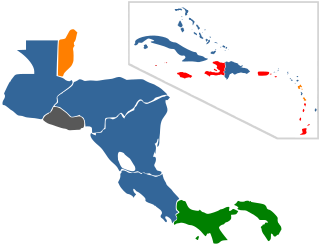

Legality of prostitution in the Americas varies by country. Most countries only legalized prostitution, with the act of exchanging money for sexual services legal. The level of enforcement varies by country. One country, the United States, is unique as legality of prostitution is not the responsibility of the federal government, but rather state, territorial, and federal district's responsibility.

Prostitution in early modern England was defined by a series of attempts by kings, queens, and other government officials to prohibit people from working in the sex industry. There was an ebb and flow to the prohibition orders, which were separated by periods of indifference at various level of the English government. Areas like Southwark that had cultivated a reputation as a hub for prostitution and entertainment, originally outside of the jurisdiction of London, were incorporated into the city during the early modern period. Some illicit businesses in these areas continued to offer their services to interested patrons more discretely, but many brothels and related businesses reemerged in less conspicuous areas of London, disguised as other kinds of businesses.