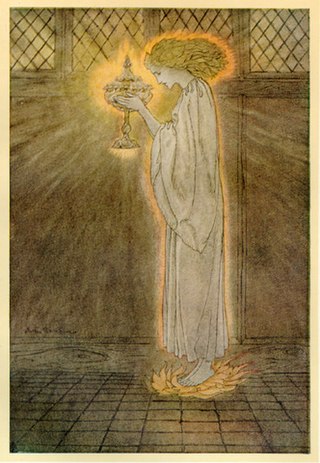

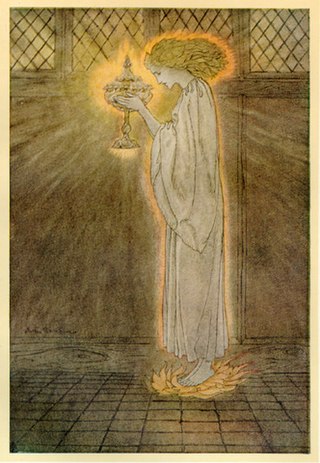

The Holy Grail is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miraculous healing powers, sometimes providing eternal youth or sustenance in infinite abundance, often guarded in the custody of the Fisher King and located in the hidden Grail castle. By analogy, any elusive object or goal of great significance may be perceived as a "holy grail" by those seeking such.

Gawain, also known in many other forms and spellings, is a character in Arthurian legend, in which he is King Arthur's nephew and one of the premier Knights of the Round Table. The prototype of Gawain is mentioned under the name Gwalchmei in the earliest Welsh sources. He has subsequently appeared in many Arthurian tales in Welsh, Latin, French, English, Scottish, Dutch, German, Spanish, and Italian, notably as the protagonist of the Middle English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Other works featuring Gawain as their central character include De Ortu Waluuanii, Diu Crône, Ywain and Gawain, Golagros and Gawane, Sir Gawain and the Carle of Carlisle, L'âtre périlleux, La Mule sans frein, La Vengeance Raguidel, Le Chevalier à l'épée, Le Livre d'Artus, The Awntyrs off Arthure, The Greene Knight, and The Weddynge of Syr Gawen and Dame Ragnell.

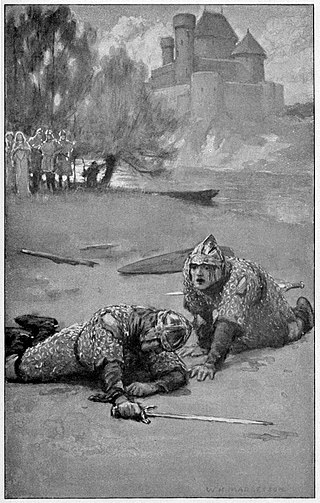

Lancelot du Lac, also written as Launcelot and other variants, is a character in some versions of Arthurian legend where he is typically depicted as King Arthur's close companion and one of the greatest Knights of the Round Table. In the French-inspired Arthurian chivalric romance tradition, Lancelot is an orphaned son of King Ban of the lost kingdom of Benoic, raised in a fairy realm by the Lady of the Lake. A hero of many battles, quests and tournaments, and famed as a nearly unrivalled swordsman and jouster, Lancelot becomes the lord of the castle Joyous Gard and personal champion of Arthur's wife, Queen Guinevere, despite suffering from frequent and sometimes prolonged fits of madness. But when his adulterous affair with Guinevere is discovered, it causes a civil war that, once exploited by Mordred, brings an end to Arthur's kingdom.

Galahad, sometimes referred to as Galeas or Galath, among other versions of his name, is a knight of King Arthur's Round Table and one of the three achievers of the Holy Grail in Arthurian legend. He is the illegitimate son of Sir Lancelot du Lac and Lady Elaine of Corbenic and is renowned for his gallantry and purity as the most perfect of all knights. Emerging quite late in the medieval Arthurian tradition, Sir Galahad first appears in the Lancelot–Grail cycle, and his story is taken up in later works, such as the Post-Vulgate Cycle, and Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur. In Arthurian literature, he replaced Percival as the hero in the quest for the Holy Grail.

The Knights of the Round Table are the legendary knights of the fellowship of King Arthur that first appeared in the Matter of Britain literature in the mid-12th century. The Knights are an order dedicated to ensuring the peace of Arthur's kingdom following an early warring period, entrusted in later years to undergo a mystical quest for the Holy Grail. The Round Table at which they meet is a symbol of the equality of its members, who range from sovereign royals to minor nobles.

Percival, alternatively called Peredur, is a figure in the legend of King Arthur, often appearing as one of the Knights of the Round Table. First mentioned by the French author Chrétien de Troyes in the tale Perceval, the Story of the Grail, he is best known for being the original hero in the quest for the Grail, before being replaced in later literature by Galahad.

Percival's sister is a role of two similar but distinct characters in the Holy Grail stories within the Arthurian legend featuring the Grail hero Percival (Perceval). The first of them is named Dindrane, the second is usually unnamed and is known today as the Grail heroine.

Red Knight is a title borne by several characters in Arthurian legend.

In Arthurian legend, the Siege Perilous is a vacant seat at the Round Table reserved by Merlin for the knight who would one day be successful in the quest for the Holy Grail.

King Pellinore is the king of Listenoise or of "the Isles" in Arthurian legend. In the tradition from the Old French prose, he is associated with the Questing Beast and is the slayer of King Lot. His many children include the sons Aglovale, Lamorak, and Percival, and the daughter Dindrane.

Gaheris is a Knight of the Round Table in the chivalric romance tradition of Arthurian legend. A nephew of King Arthur, Gaheris is the third son of Arthur's sister or half-sister Morgause and her husband Lot, King of Orkney and Lothian. He is the younger brother of Gawain and Agravain, the older brother of Gareth, and half-brother of Mordred. His figure may have been originally derived from that of a brother of Gawain in the early Welsh tradition, and then later split into a separate character of another brother, today best known as Gareth. German poetry also described him as Gawain's cousin instead of brother.

Parzival is a medieval chivalric romance by the poet and knight Wolfram von Eschenbach in Middle High German. The poem, commonly dated to the first quarter of the 13th century, centers on the Arthurian hero Parzival and his long quest for the Holy Grail following his initial failure to achieve it.

Agravain is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend, whose first known appearance is in the works of Chrétien de Troyes. He is the second eldest son of King Lot of Orkney with one of King Arthur's sisters known as Anna or Morgause, thus nephew of King Arthur, and brother to Sir Gawain, Gaheris, and Gareth, as well as half-brother to Mordred. Agravain secretly makes attempts on the life of his hated brother Gaheris since the Vulgate Cycle, participates in the slayings of Lamorak and Palamedes in the Post-Vulgate Cycle, and murders Dinadan in the Prose Tristan. In the French prose cycle tradition included in Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, together with Mordred, he then plays a leading role by exposing his aunt Guinevere's affair with Lancelot, which leads to his death at Lancelot's hand.

Perceval, the Story of the Grail is the unfinished fifth verse romance by Chrétien de Troyes, written by him in Old French in the late 12th century. Later authors added 54,000 more lines to the original 9,000 in what are known collectively as the Four Continuations, as well as other related texts. Perceval is the earliest recorded account of what was to become the Quest for the Holy Grail but describes only a golden grail in the central scene, does not call it "holy" and treats a lance, appearing at the same time, as equally significant. Besides the eponymous tale of the grail and the young knight Perceval, the poem and its continuations also tell of the adventures of Gawain and some other knights of King Arthur.

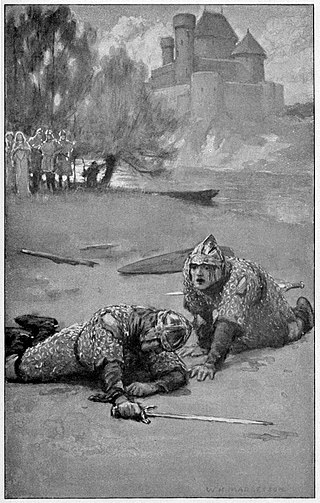

Balinthe Savage, also known as the Knight with the Two Swords, is a character in the Arthurian legend. Like Galahad, Balin is a late addition to the medieval Arthurian world. His story, as told by Thomas Malory in Le Morte d'Arthur, is based upon that told in the continuation of the second book of the Post-Vulgate cycle of legend, the Suite du Merlin.

The Dolorous Stroke is a trope in Arthurian legend and some other stories of Celtic origin. In its fullest form, it concerns the Fisher King, the guardian of the Holy Grail, who falls into sin and consequently suffers a wound from a mystical weapon. He becomes the Maimed King, and his kingdom suffers similarly, becoming the Wasteland: neither will be healed until the successful completion of the Grail Quest.

The Wasteland is a Celtic motif that ties the barrenness of a land with a curse that must be lifted by a hero. It occurs in Irish mythology and French Grail romances, and hints of it may be found in the Welsh Mabinogion.

Corbenic is the name of the Grail castle, the edifice housing the Holy Grail in Arthurian legend. It is a magical domain of the Grail keeper, often known as the Fisher King. The castle's descriptions vary greatly in different sources, and it first appears by that name in the Lancelot-Grail cycle where it is also the birthplace of Galahad.

Perlesvaus, also called Li Hauz Livres du Graal, is an Old French Arthurian romance dating to the first decade of the 13th century. It purports to be a continuation of Chrétien de Troyes' unfinished Perceval, the Story of the Grail, but it has been called the least canonical Arthurian tale because of its striking differences from other versions.

Elaine or Elizabeth, also known as Amite, and identified as the "Grail Maiden" or the "Grail Bearer", is a character from Arthurian legend. In the Arthurian chivalric romance tradition from the Vulgate Cycle, she is the daughter of the Fisher King, King Pelles of Corbenic, and the mother of Galahad by Lancelot, whose repeated rape by her results in his descent into madness. She should not be confused with Elaine of Astolat, a different woman who too fell in love with Lancelot.