Anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. The earliest known human remains in South Asia date to 30,000 years ago. Sedentariness began in South Asia around 7000 BCE; by 4500 BCE, settled life had spread, and gradually evolved into the Indus Valley Civilisation, which flourished between 2500 BCE and 1900 BCE in present-day Pakistan and north-western India. Early in the second millennium BCE, persistent drought caused the population of the Indus Valley to scatter from large urban centres to villages. Indo-Aryan tribes moved into the Punjab from Central Asia in several waves of migration. The Vedic Period of the Vedic people in northern India was marked by the composition of their large collections of hymns (Vedas). The social structure was loosely stratified via the varna system, which has been incorporated into the highly evolved present-day Jāti-system. The pastoral and nomadic Indo-Aryans spread from the Punjab into the Gangetic plain. Around 600 BCE, a new, interregional culture arose; then, small chieftaincies (janapadas) were consolidated into larger states (mahajanapadas). A second urbanisation took place, which came with the rise of new ascetic movements and religious concepts, including the rise of Jainism and Buddhism. The latter was synthesised with the preexisting religious cultures of the subcontinent, giving rise to Hinduism.

The Indian Independence Movement, was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British rule in India. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

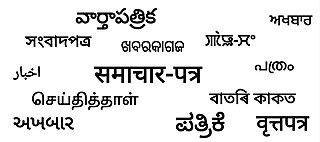

Mass media in India consists of several different means of communication: television, radio, cinema, newspapers, magazines, and Internet-based websites/portals. Indian media was active since the late 18th century. The print media started in India as early as 1780. Radio broadcasting began in 1927. Today much of the media is controlled by large, corporations, which reap revenue from advertising, subscriptions, and sale of copyrighted material.

The Bengal Presidency, officially the Presidency of Fort William in Bengal and later Bengal Province, was a province of British India and the largest of all the three Presidencies. At the height of its territorial jurisdiction, it covered large parts of what is now South Asia and Southeast Asia. Bengal proper covered the ethno-linguistic region of Bengal. Calcutta, the city which grew around Fort William, was the capital of the Bengal Presidency. For many years, the Governor of Bengal was concurrently the Governor-General of India and Calcutta was the capital of India until 1911.

The history of Bengal is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and the surrounding regions of South Asia and Southeast Asia. It includes modern-day Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam's Karimganj district, located in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent, at the apex of the Bay of Bengal and dominated by the fertile Ganges delta. The region was known to the ancient Greeks and Romans as Gangaridai, a powerful kingdom whose war elephant forces led the withdrawal of Alexander the Great from India. Some historians have identified Gangaridai with other parts of India. The Ganges and the Brahmaputra rivers act as a geographic marker of the region, but also connects the region to the broader Indian subcontinent. Bengal, at times, has played an important role in the history of the Indian subcontinent.

The Bengal Renaissance, also known as the Bengali Renaissance, was a cultural, social, intellectual, and artistic movement that took place in the Bengal region of the British Raj, from the late 18th century to the early 20th century. Historians have traced the beginnings of the movement to the victory of the British East India Company at the 1757 Battle of Plassey, as well as the works of reformer Raja Rammohan Roy, considered the "Father of the Bengal Renaissance," born in 1772. Nitish Sengupta stated that the movement "can be said to have … ended with Rabindranath Tagore," Asia's first Nobel laureate.

The British Raj was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent; it is also called Crown rule in India, or Direct rule in India, and lasted from 1858 to 1947. The region under British control was commonly called India in contemporaneous usage and included areas directly administered by the United Kingdom, which were collectively called British India, and areas ruled by indigenous rulers, but under British paramountcy, called the princely states. The region was sometimes called the Indian Empire, though not officially.

The Press Act of 1908 was legislation promulgated in British India imposing strict censorship on all kinds of publications. The measure was brought into effect to curtail the influence of Indian vernacular and English language in promoting support for what was considered radical Indian nationalism. this act gave the British rights to imprison and execute anyone who writes radical articles in the newspapers. It followed in the wake of two decades of increasing influence of journals such as Kesari in Western India, publications such as Jugantar and Bandemataram in Bengal, and similar journals emerging in the United Provinces. These were deemed to influence a surge in nationalist violence and revolutionary terrorism against interests and officials of the Raj in India, particularly in Maharashtra and in Bengal. A widespread influence was noted amongst the general population which drew a large proportion population of youth towards the ideology of radical nationalists such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Aurobindo Ghosh, and towards secret revolutionary organisations such as Anushilan Samiti in Bengal and Mitra Mela in Maharashtra. This peaked in 1908, with the attempted assassination of a local judge in Bengal, and a number of assassinations of local Raj officials in Maharshtra. The aftermath of Muzaffarpur bombings saw Tilak convicted on charges of sedition, while in Bengal a large number of nationalists of the Anushilan Samiti were convicted. However, Aurobindo Ghosh had escaped conviction. With defiant messages from journals such as Jugantar, the propvisions of the 1878 Vernacular Press Act were revived. Herbert Hope Risley, in 1907, declared, "We are overwhelmed with a mass of heterogeneous material, some of it misguided, some of it frankly seditious," in response to a deluge of imagery associated with the Cow Protection Movement. These concerns led him to draft the major substance of the 1910 Press Act.

Al-Hilal was a weekly Urdu language newspaper established by the Indian Muslim independence activist and first education minister of India Maulana Abul Kalam Azad. The paper was notable for its criticism of the British Raj in India and its exhortation to Indian Muslims to join the growing Indian independence movement. Al-Hilal ran from 1912 to 1914, when it was shut down under the Press Act.

The Goa liberation movement was a movement which fought to end Portuguese colonial rule in Goa, Portuguese India. The movement built on the small scale revolts and uprisings of the 19th century, and grew powerful during the period 1940–1961. The movement was conducted both inside and outside Goa, and was characterised by a range of tactics including nonviolent demonstrations, revolutionary methods and diplomatic efforts. However, Portuguese control of its Indian colonies ended only when India invaded and annexed Goa in 1961, causing a mixture of worldwide acclaim and condemnation, and incorporated the territories into India.

In British India, the Vernacular Press Act (1878) was enacted to curtail the freedom of the Indian press and prevent the expression of criticism toward British policies—notably, the opposition that had grown with the outset of the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–80). The government adopted the Vernacular Press Act 1878 to regulate the indigenous press in order to manage strong public opinion and seditious writing producing unhappiness among the people of native region with the government. The Act was proposed by Lytton, then Viceroy of India, and was unanimously passed by the Viceroy's Council on 14 March 1878. The act excluded English-language publications as it was meant to control seditious writing in 'publications in Oriental languages' everywhere in the country, except for the South. Thus the British totally discriminated against the Indian Press.

The Serampore Mission Press was a book and newspaper publisher that operated in Serampore, Danish India, from 1800 to 1837.

In the last quarter of the 18th century, Calcutta grew into the first major centre of commercial and government printing. For the first time in the context of South Asia it becomes possible to talk of a nascent book trade which was full-fledged and included the operations of printers, binders, subscription publishing and libraries.

Hindusthan Samachar is the first multilingual news agency in India, subscribed by more than 200 newspapers and almost all the news channels including Doordarshan (DD).

James Augustus Hicky was an Irishman who launched the first printed newspaper in India, Hicky's Bengal Gazette.

The Media in Gujarati language started with publication of Bombay Samachar in 1822. Initially the newspapers published business news and they were owned by Parsi people based in Bombay. Later Gujarati newspapers started published from other parts of Gujarat. Several periodicals devoted to social reforms were published in the second half of the 19th century. After arrival of Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian independence movement peaked and it resulted in proliferation of Gujarati media. Following independence, the media was chiefly focused on political news. After bifurcation of Bombay state, the area of service changed. Later there was an increase in readership due to growth of literacy and the media houses expanded its readership by publishing more editions. Later these media houses ventured into digital media also. The radio and television media expanded after 1990.

United News of India, abbreviated as UNI, is a multilingual news agency in India. It was founded On 19 December 1959 as an English news agency. Its commercial operations were started from 21 March 1961. With its Univarta, a Hindi news service, UNI became one of the multilingual news service in the world. In 1992, it started its Urdu news service and hence became the first news agency to provide Urdu news. Currently, it is the second largest news agency in India, supplying news in English, Hindi, Urdu and Kannada languages. Its news bureaus are present in all state capitals and major cities of India.

Akshay Kumar Jain (1915–1993) was an Indian independence activist, writer, journalist and the editor of Navbharat Times, a Hindi-language daily owned by The Times Group. He was one of the founders of the National Union of Journalists (India) and held the chair of its reception committee when the organization was formed in 1972.

Payam-e-Azadi, was an Urdu and Hindi language daily newspaper published by Azimullah Khan and edited by Mirza Bedar Bakht, grandson of the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar. It first started publishing in February 1857 from Delhi and later appeared in Jhansi.

Censorship in the Dutch East Indies was significantly stricter than in the Netherlands, as the freedom of the press guaranteed in the Constitution of the Netherlands did not apply in the country's overseas colonies. Before the twentieth century, official censorship focused mainly on Dutch-language materials, aiming at protecting the trade and business interests of the colony and the reputation of colonial officials. In the early twentieth century, with the rise of Indonesian nationalism, censorship also encompassed materials printed in local languages such as Malay and Javanese, and enacted a repressive system of arrests, surveillance and deportations to combat anti-colonial sentiment.