The history of South Korea begins with the Japanese surrender on 2 September 1945. At that time, South Korea and North Korea were divided, despite being the same people and on the same peninsula. In 1950, the Korean War broke out. North Korea overran South Korea until US-led UN forces intervened. At the end of the war in 1953, the border between South and North remained largely similar. Tensions between the two sides continued. South Korea alternated between dictatorship and liberal democracy. It underwent substantial economic development.

Cha Bum-kun is a South Korean former football manager and player. A forward, he was nicknamed Tscha Bum or "Cha Boom" in Germany because of his name and thunderous ball striking ability. He showed explosive pace and powerful shots with his thick thighs. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest Asian footballers of all time.

Cheong Wa Dae, also known as the Blue House in English, is a public park that formerly served as the presidential residence and the diplomatic reception halls of South Korea from 1948 to 2022. It is located in the Jongno district of the South Korean capital Seoul.

The Dong-a Ilbo is a daily Korean-language newspaper published in South Korea. It is considered a newspaper of record in the country, and was founded in 1920. The paper has been a significant presence in Korean society and history, especially during the 1910–1945 Japanese colonial period, when it championed the Korean independence movement.

Park Geun-hye is a South Korean politician who served as the 11th president of South Korea from 2013 to 2017, when she was impeached and convicted on related corruption charges.

Human rights in South Korea are codified in the Constitution of the Republic of Korea, which compiles the legal rights of its citizens. These rights are protected by the Constitution and include amendments and national referendum. These rights have evolved significantly from the days of military dictatorship to the current state as a constitutional democracy with free and fair elections for the presidency and the members of the National Assembly.

Censorship in South Korea is implemented by various laws that were included in the constitution as well as acts passed by the National Assembly over the decades since 1948. These include the National Security Act, whereby the government may limit the expression of ideas that it perceives "praise or incite the activities of anti-state individuals or groups". Censorship was particularly severe during the country's authoritarian era, with freedom of expression being non-existent, which lasted from 1948 to 1993.

The South Korean mass media consist of several different types of public communication of news: television, radio, cinema, newspapers, magazines, and Internet-based websites.

The Kyunghyang Shinmun (Korean: 경향신문) or Kyonghyang Sinmun is a major daily newspaper published in South Korea. It is based in Seoul. The name literally means Urbi et Orbi Daily News.

The Lee Myung-bak government was the fifth government of the Sixth Republic of South Korea. It took office on 25 February 2008 after Lee Myung-bak's victory in the 2007 presidential elections. Most of the new cabinet was approved by the National Assembly on 29 February. Led by President Lee Myung-bak, it was supported principally by the conservative Saenuri Party, previously known as the Grand National Party. It was also known as Silyong Jeongbu, the "pragmatic government", a name deriving from Lee's campaign slogan.

The New Right movement in South Korean politics is a school of political thought which developed as a reaction against the traditional divide between conservatives and progressives. The New Right broke from past conservatives, who supported state intervention in the economy, by promoting economically liberal ideas. Many figures of the New Right have also become notable for criticising anti-Japanese sentiment in South Korea. Opponents of the New Right movement described this as anti-leftism, military dictatorship advocates, pro-sadaejuui, and "pro-Japanese identity".

Kim Young-sam, often referred to by his initials YS, was a South Korean politician and activist who served as the 7th president of South Korea from 1993 to 1998.

In 2013, there were two major sets of cyberattacks on South Korean targets attributed to elements within North Korea.

Chin Young is a South Korean politician in the liberal Democratic Party of Korea, and a former member of the National Assembly representing Yongsan, Seoul. He was formerly a member of the conservative Saenuri Party, and served as the first Minister of Health and Welfare in the Park Geun-hye administration from March to September 2013.

Freedom of the press in East Timor is protected by section 41 of the Constitution of East Timor.

The 2016 South Korean political scandal, often called Park Geun-hye–Choi Soon-sil Gate in South Korea, was a scandal that emerged around October 2016 in relation to the unusual access that Choi Soon-sil, the daughter of shaman-esque cult leader Choi Tae-min, had to President Park Geun-hye of South Korea.

Tatsuya Kato is a Japanese journalist who was a Seoul bureau chief of South Korea at Sankei Shimbun.

The impeachment of Park Geun-hye, President of South Korea, was the culmination of a political scandal involving interventions to the presidency from her aide, Choi Soon-sil. The impeachment vote took place on 9 December 2016, with 234 members of the 300-member National Assembly voting in favour of the impeachment and temporary suspension of Park Geun-hye's presidential powers and duties. This exceeded the required two-thirds threshold in the National Assembly and, although the vote was by secret ballot, the results indicated that more than half of the 128 lawmakers in Park's party Saenuri had supported her impeachment. Thus, Hwang Kyo-ahn, then Prime Minister of South Korea, became Acting President while the Constitutional Court of Korea was due to determine whether to accept the impeachment. The court upheld the impeachment in a unanimous 8–0 decision on 10 March 2017, removing Park from office. The regularly scheduled presidential election was advanced to 9 May 2017, and Moon Jae-in, former leader of the Democratic Party, was elected as Park's permanent successor.

Political repression in South Korea refers to the physical or psychological maltreatment, including different levels of threats suffered by individuals or groups in South Korea for different kinds of political reasons throughout the country's history.

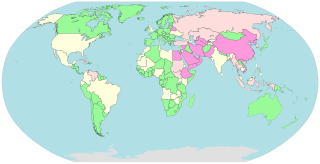

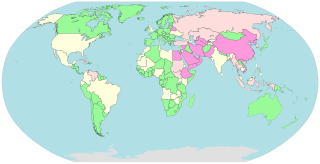

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Africa provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Africa.