The European macroseismic scale (EMS) is the basis for evaluation of seismic intensity in European countries and is also used in a number of countries outside Europe. Issued in 1998 as an update of the test version from 1992, the scale is referred to as EMS-98.

The Medvedev–Sponheuer–Karnik scale, also known as the MSK or MSK-64, is a macroseismic intensity scale used to evaluate the severity of ground shaking on the basis of observed effects in an area where an earthquake transpires.

An earthquake occurred at on 8 October in Azad Kashmir. It was centred near the city of Muzaffarabad, and also affected nearby Balakot in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and some areas of Jammu and Kashmir. It registered a moment magnitude of 7.6 and had a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (Extreme). The earthquake was also felt in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, India, and the Xinjiang region. The severity of the damage caused by the earthquake is attributed to severe upthrust. Over 86,000 people died, a similar number were injured, and millions were displaced. It is considered the deadliest earthquake in South Asia, surpassing the 1935 Quetta earthquake.

The 1356 Basel earthquake is the most significant seismological event to have occurred in Central Europe in recorded history and had a moment magnitude in the range of 6.0–7.1. This earthquake, which occurred on 18 October 1356, is also known as the Sankt-Lukas-Tag Erdbeben, as 18 October is the feast day of Saint Luke the Evangelist.

The 1927 Crimean earthquakes occurred in the month of June and again in September in the waters of the Black Sea near the Crimean Peninsula. Each of the submarine earthquakes in the sequence triggered tsunami. The June event was moderate relative to the large September 11 event, which had at least one aftershock that also generated a tsunami. Following the large September event, natural gas that was released from the sea floor created flames that were visible along the coastline, and was accompanied by bright flashes and explosions.

The Galilee earthquake of 363 was a pair of severe earthquakes that shook the Galilee and nearby regions on May 18 and 19. The maximum perceived intensity for the events was estimated to be VII on the Medvedev–Sponheuer–Karnik scale. The earthquakes occurred on the portion of the Dead Sea Transform (DST) fault system between the Dead Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba.

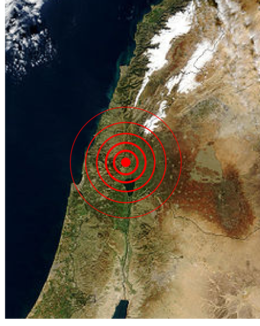

In seismology, an isoseismal map is used to show lines of equally felt seismic intensity, generally measured on the Modified Mercalli scale. Such maps help to identify earthquake epicenters, particularly where no instrumental records exist, such as for historical earthquakes. They also contain important information on ground conditions at particular locations, the underlying geology, radiation pattern of the seismic waves, and the response of different types of buildings. They form an important part of the macroseismic approach, i.e. that part of seismology dealing with noninstrumental data. The shape and size of the isoseismal regions can be used to help determine the magnitude, focal depth, and focal mechanism of an earthquake.

The 1995 Gulf of Aqaba earthquake occurred on November 22 at 06:15 local time and registered 7.3 on the scale. The epicenter was located in the central segment of the Gulf of Aqaba, the narrow body of water that separates Egypt's Sinai Peninsula from the western border of Saudi Arabia. At least 8 people were killed and 30 were injured in the meizoseismal area.

The 1967 Mudurnu earthquake or more correctly, the 1967 Mudurnu Valley earthquake occurred at about 18:57 local time on 22 July near Mudurnu, Bolu Province, north-western Turkey. The magnitude 7.4 earthquake was one of a series of major and intermediate quakes that have occurred in modern times along the North Anatolian Fault since 1939.

The 1927 Jericho earthquake was a devastating event that shook Mandatory Palestine and Transjordan on July 11 at . The epicenter of the earthquake was in the northern area of the Dead Sea. The cities of Jerusalem, Jericho, Ramle, Tiberias, and Nablus were heavily damaged and at least 287 were estimated to have been killed.

The 1935 Sumatra earthquake occurred at on 28 December. It had a magnitude of 7.7 and a maximum felt intensity of VII (Damaging) on the European macroseismic scale. It triggered a minor tsunami.

The 2003 Zhaosu earthquake, also known as the Syumbinskoe earthquake, occurred on December 1 at 01:38 UTC. The epicenter was located in the Almaty Region, Kazakhstan, near the Sino–Kazakh border. The earthquake had a magnitude of 6.0 and had a maximum observed intensity of VII on the Medvedev–Sponheuer–Karnik scale. The epicenter was close to the Zhaosu County, Xinjiang, where 10 people were reported dead, 73 people injured, and more than 800 buildings collapsed. Some people were evacuated in Zhaosu. The earthquake occurred in the cold winter, and the 30 cm ground snow covered the roads in the mountainous region and hindered the relief work.

The 1959 Kamchatka earthquake occurred on May 4 at with a moment magnitude of 8.0–8.3, and a surface wave magnitude of 8.25. The epicenter was near the Kamchatka Peninsula, Russian SFSR, USSR. Building damage was reported in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. The maximum intensity was VIII (Damaging) on the Medvedev–Sponheuer–Karnik scale. The intensity in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky was about VIII MSK.

The 1969 Sharm El Sheikh earthquake occurred on March 31 off the southern Sinai Peninsula in northeastern Egypt. The epicenter was located near Shadwan island, southwest of the city of Sharm El Sheikh, at the confluence of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Suez. This normal-slip shock measured 6.6 on the moment magnitude scale, had a maximum reported intensity of VII on the Mercalli intensity scale, and was responsible for several deaths and injuries.

On 11 September 1275, an earthquake struck the south of Great Britain. The epicentre is unknown, although it may have been in the Portsmouth/Chichester area on the south coast of England or in Glamorgan, Wales. The earthquake is known for causing the destruction of St Michael's Church on Glastonbury Tor in Somerset.

The 1885 Kashmir earthquake, also known as the Baramulla earthquake occurred on 30 May in Srinagar. It had an estimated moment magnitude of Mw 6.3–6.8 and maximum Medvedev–Sponheuer–Karnik scale intensity of VIII (Damaging). At least 3,081 people died and severe damage resulted.

The northern part of the Ottoman Empire was struck by a major earthquake on 13 August 1822. It had an estimated magnitude of 7.0 and a maximum felt intensity of IX (Destructive) on the European macroseismic scale (EMS). It may have triggered a tsunami, affecting nearby coasts. Damaging aftershocks continued for more than two years, with the most destructive being on 5 September 1822. The earthquake was felt over a large area including Rhodes, Cyprus and Gaza. The total death toll reported for this whole earthquake sequence ranges between 30,000 and 60,000, although 20,000 is regarded as a more likely number.

The 1803 Garhwal earthquake occurred in the early morning of September 1 at 01:30 local time. The estimated 7.8-magnitude-earthquake had an epicenter in the Garhwal Himalaya near Uttarkashi, British India. Major damage occurred in the Himalaya and Indo-Gangetic Plain, with the loss of between 200 and 300 lives. It is among the largest Himalaya earthquakes of the 19th-century, caused by thrust faulting.

On 5 September 1996 at 22:44 local time, southern Dalmatia, Croatia, was hit by a strong earthquake of moment magnitude 6.0. The epicentre was near the coastline of the Adriatic Sea, close to the village of Slano, roughly 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) northwest of Dubrovnik. The worst damage was of intensity VIII on the Medvedev–Sponheuer–Karnik scale, occurring in the epicentral area, but also another 25 km (16 mi) northwest, at the isthmus of the Pelješac peninsula, around the old town of Ston.