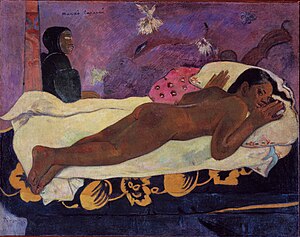

In folklore, a ghost is the soul or spirit of a dead person or non-human animal that is believed to be able to appear to the living. In ghostlore, descriptions of ghosts vary widely, from an invisible presence to translucent or barely visible wispy shapes to realistic, lifelike forms. The deliberate attempt to contact the spirit of a deceased person is known as necromancy, or in spiritism as a séance. Other terms associated with it are apparition, haunt, haint, phantom, poltergeist, shade, specter, spirit, spook, wraith, demon, and ghoul.

Polynesian mythology encompasses the oral traditions of the people of Polynesia together with those of the scattered cultures known as the Polynesian outliers. Polynesians speak languages that descend from a language reconstructed as Proto-Polynesian – probably spoken in the Tonga and Samoa area around 1000 BC.

Māui or Maui is the great culture hero and trickster in Polynesian mythology. Very rarely was Māui actually worshipped, being less of a deity (Demigod) and more of a folk hero. His origins vary from culture to culture, but many of his main exploits remain relatively similar.

Hina is the name assigned to a number of Polynesian deities. The name Hina usually relates to a powerful female force who has dominion over a specific entity. Some variations of the name Hina include Sina, Hanaiakamalama, and Ina. Even within a single culture, Hina could refer to multiple goddesses and the distinction between the different identities are not always clear. In Hawaiian mythology, the name is usually paired with words which explain or identify the goddess and her power such as Hina-puku-iʻa (Hina-gathering-seafood) the goddess of fishermen, and Hina-ʻopu-hala-koʻa who gave birth to all reef life.

In Hawaiian religion, Hiʻiaka is a daughter of Haumea and Kāne.

Hine-nui-te-pō in Māori legends, is a goddess of night and she receives the spirits of humans when they die. She is the daughter of Tāne Mahuta / Tāne Tuturi and Hine-ahuone. It is believed among Māori that the colour red in the sky comes from her. Hine-nui-te-pō shepherds the wairua/souls into the first level of Rarohenga to ready them for the next stage of their journey. Before she was Hine-nui-te-po her name was Hine-ti-tama. Her father Tane Mahuta took her virginity; she then felt ashamed, hiding herself in internal darkness to hide from her father and became Hine-nui-te-po, goddess of the night.

In Hawaiian mythology, Laka is the name of two different popular heroes from Polynesian mythology..

In Hawaiian mythology, the Kupua are a group of supernatural entities which might be considered gods or spirits.

In Polynesian mythology, Hawaiki is the original home of the Polynesians, before dispersal across Polynesia. It also features as the underworld in many Māori stories.

In Hawaiian religion, Pele is the goddess of volcanoes and fire and the creator of the Hawaiian Islands. Often referred to as "Madame Pele" or "Tūtū Pele" as a sign of respect, she is a well-known deity within Hawaiian mythology and is notable for her contemporary presence and cultural influence as an enduring figure from ancient Hawaii. Epithets of the goddess include Pele-honua-mea and Ka wahine ʻai honua.

The culture of the Native Hawaiians encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms practiced by the original residents of the Hawaiian islands, including their knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits. Humans are estimated to have first inhabited the archipelago between 124 and 1120 AD when it was settled by Polynesians who voyaged to and settled there. Polynesia is made of multiple island groups which extend from Hawaii to New Zealand across the Pacific Ocean. These voyagers developed Hawaiian cuisine, Hawaiian art, and the Native Hawaiian religion.

Cordyline fruticosa is an evergreen flowering plant in the family Asparagaceae. The plant is of great cultural importance to the traditional animistic religions of Austronesian and Papuan peoples of the Pacific Islands, New Zealand, Island Southeast Asia, and Papua New Guinea. It is also cultivated for food, traditional medicine, and as an ornamental for its variously colored leaves. It is identified by a wide variety of common names, including ti plant, palm lily, cabbage palm.

In Hawaiian religion, Māui is a culture hero and ancient chief who appears in several different genealogies. In the Kumulipo, he is the son of ʻAkalana and his wife Hina-a-ke-ahi (Hina). This couple has four sons, Māui-mua, Māui-waena, Māui-kiʻikiʻi, and Māui-a-kalana. Māui-a-kalana's wife is named Hinakealohaila, and his son is named Nanamaoa. Māui is one of the Kupua. His name is the same as that of the Hawaiian island Maui, although native tradition holds that it is not named for him directly, but instead named after the son of Hawaii's discoverer.

In Samoan legend, the mythological figure Tiʻitiʻi Atalaga appears in legends very similar to those recounting the tales of the demigod Māui, found in other island cultures. In one such legend, which is almost identical to the New Zealand fire myth of Māui Tikitiki-a-Taranga, he succeeds in bringing fire to the people of Samoa after a battle with the earthquake god, Mafuiʻe. During the battle, Ti'iti'i breaks off one of Mafui'e's arms, forcing him to agree to teach him of how fire had been concealed by the gods in certain trees during the making of the world. The people of Samoa were thankful to Ti'iti'i for breaking off Mafui'e's arm, as they believed that he was less able to create large earthquakes as a result.

Hawaiian religion refers to the indigenous religious beliefs and practices of native Hawaiians, also known as the kapu system. Hawaiian religion is based largely on the tapu religion common in Polynesia and likely originated among the Tahitians and other Pacific islanders who landed in Hawaiʻi between 500 and 1300 AD. It is polytheistic and animistic, with a belief in many deities and spirits, including the belief that spirits are found in non-human beings and objects such as other animals, the waves, and the sky. It was only during the reign of Kamehameha I that a ruler from Hawaii island attempted to impose a singular "Hawaiian" religion on all the Hawaiian islands that was not Christianity.

Pili line was a royal house in ancient Hawaii that ruled over the island of Hawaiʻi with deep roots in the history of Samoa and possibly beyond further to the west, Ao-Po, in Pulotu, the Samoan Underworld. It was founded on unknown date by King Pilikaʻaiea (Pili), who either was born in or came from either Upolu, Samoa or Uporu, Tahiti, but came to Hawaii and established his own dynasty of kings (Aliʻi). The overall arc of his career describes a brilliant young chief from foreign lands who was eager to share his abundant knowledge of advanced technology with distant frontier rustics. Some stories relate how his ambition got the better of him and damaged his relationships with his subjects. These stories cast him as a libidinous, restless and petty tyrant ever on the move searching for new conquests.

Saveasiʻuleo is the God of Pulotu the underworld of spirits or Hades in Samoan mythology.

Mangarevan narrative comprises the legends, historical tales, and sayings of the ancient Mangarevan people. It is considered a variant of a more general Polynesian narrative, developing its own unique character for several centuries before the 1830s. The religion was officially suppressed in the 19th century, and ultimately abandoned by the natives in favor of Roman Catholicism. The Mangarevan term for god was Etua.

Ghostlore is an intricate web of traditional beliefs and folklore surrounding ghosts and hauntings. Ghostlore has ingrained itself in the cultural fabric of societies worldwide. Defined by narratives often featuring apparitions of the deceased, ghostlore stands as a universal phenomenon, with roots extending deeply into human history.