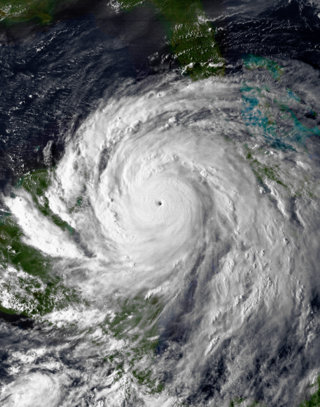

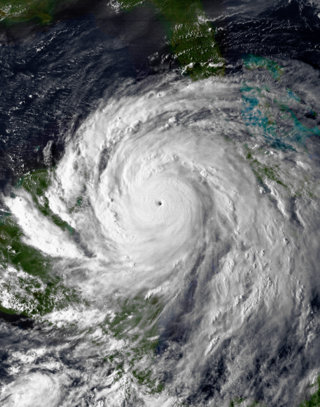

Hurricane Gilbert was the second most intense tropical cyclone on record in the Atlantic basin in terms of barometric pressure, only behind Hurricane Wilma in 2005. An extremely powerful tropical cyclone that formed during the 1988 Atlantic hurricane season, Gilbert peaked as a Category 5 strength hurricane that brought widespread destruction to the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, and is tied with 1969's Hurricane Camille as the second-most intense tropical cyclone to make landfall in the Atlantic Ocean. Gilbert was also one of the largest tropical cyclones ever observed in the Atlantic basin. At one point, its tropical storm-force winds measured 575 mi (925 km) in diameter. In addition, Gilbert was the most intense tropical cyclone in recorded history to strike Mexico.

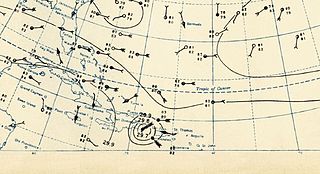

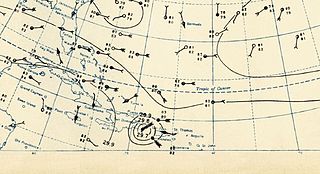

The 1950 Atlantic hurricane season was the first year in the Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT) that storms were given names in the Atlantic basin. Names were taken from the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet, with the first named storm being designated "Able", the second "Baker", and so on. It was a very active season with sixteen tropical storms, with eleven of them developing into hurricanes. Six of these hurricanes were intense enough to be classified as major hurricanes—a denomination reserved for storms that attained sustained winds equivalent to a Category 3 or greater on the present-day Saffir–Simpson scale. One storm, the twelfth of the season, was unnamed and was originally excluded from the yearly summary, and three additional storms were discovered in re-analysis. The large quantity of strong storms during the year yielded, prior to modern reanalysis, what was the highest seasonal accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) of the 20th century in the Atlantic basin; 1950 held the seasonal ACE record until broken by the 1995 Atlantic hurricane season. However, later examination by researchers determined that several storms in the 1950 season were weaker than thought, leading to a lower ACE than assessed originally. This season also set the record for the most tropical storms, eight, in the month of October.

The 1951 Atlantic hurricane season was the first hurricane season in which tropical cyclones were officially named by the United States Weather Bureau. The season officially started on June 15, when the United States Weather Bureau began its daily monitoring for tropical cyclone activity; the season officially ended on November 15. It was the first year since 1937 in which no hurricanes made landfall on the United States; as Hurricane How was the only tropical storm to hit the nation, the season had the least tropical cyclone damage in the United States since the 1939 season. As in the 1950 season, names from the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet were used to name storms this season.

The 1947 Atlantic hurricane season was the first Atlantic hurricane season to have tropical storms labeled by the United States Air Force. The season officially began on June 16, 1947, and ended on November 1, 1947. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. However, the first tropical cyclone developed on June 13, while the final system was absorbed by a cold front on December 1. There were 10 tropical storms; 5 of them attained hurricane status, while two became major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the modern day Saffir–Simpson scale. Operationally, the third tropical storm was considered two separate tropical cyclones, resulting in the storm receiving two names. The eighth tropical storm went undetected and was not listed in HURDAT until 2014.

The 1946 Atlantic hurricane season resulted in no fatalities in the United States. The season officially began on June 15, 1946, and lasted until November 15, 1946. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. However, the first storm, developed in the Gulf of Mexico on June 13, while the final system dissipated just offshore Florida on November 3. There were seven tropical storms; three of them attained hurricane status, while none intensified into major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. This had not occurred since 1940 and would not again until 1968. Operationally, the fifth tropical storm, which existed near the Azores in early October, was not considered a tropical cyclone but was added to HURDAT in 2014.

The 1933 Atlantic hurricane season is the most active Atlantic hurricane season on record in terms of accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE), with a total of 259. It also set a record for nameable tropical storms in a single season, 20, which stood until 2005, when there were 28 storms. The season ran for six months of 1933, with tropical cyclone development occurring as early as May and as late as November. A system was active for all but 13 days from June 28 to October 7.

The 1938 Atlantic hurricane season produced fifteen tropical cyclones, of which nine strengthened into tropical storms. Four storms intensified into hurricanes. Two of those four became major hurricanes, the equivalent of a Category 3 or greater storm on the modern day Saffir–Simpson scale. The hurricane season officially began on June 16 and ended on November 15. In 2012, as part of the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project, meteorologists identified a previously undocumented January hurricane and September tropical storm while fine-tuning the meteorological histories of several others. However, given scant observations from ships and weather stations, significant uncertainty of tropical cyclone tracks, intensity, and duration remains, particularly for those storms that stayed at sea.

The 1916 Atlantic hurricane season featured eighteen tropical cyclones, of which nine made landfall in the United States, the most in one season until 2020, when eleven struck. The first storm appeared on May 13 south of Cuba, while the final tropical storm became an extratropical cyclone over the southeastern Gulf of Mexico on November 15. Of the 18 tropical cyclones forming that season, 15 intensified into a tropical storm, the second-most at the time, behind only 1887. Ten of the tropical storms intensified into a hurricane, while five of those became a major hurricane. The early 20th century lacked modern forecasting tools such as satellite imagery and documentation, and thus, the hurricane database from these years may be incomplete.

The 1915 Atlantic hurricane season featured the strongest tropical cyclone to make landfall in the United States since the 1900 Galveston hurricane. The first storm, which remained a tropical depression, appeared on April 29 near the Bahamas, while the final system, also a tropical depression, was absorbed by an extratropical cyclone well south of Newfoundland on October 22. Of the six tropical storms, five intensified into a hurricane, of which three further strengthened into a major hurricane. Four of the hurricanes made landfall in the United States. The early 20th century lacked modern forecasting and documentation, and thus, the hurricane database from these years may be incomplete.

The 1912 Atlantic hurricane season was an average hurricane season that featured the first recorded November major hurricane. There were eleven tropical cyclones, seven of which became tropical storms; four of those strengthened into hurricanes, and one reached major hurricane intensity. The season's first cyclone developed on April 4, while the final dissipated on November 21. The season's most intense and most devastating tropical cyclone was the final storm, known as the Jamaica hurricane. It produced heavy rainfall on Jamaica, leading to at least 100 fatalities and about $1.5 million (1912 USD) in damage. The storm was also blamed for five deaths in Cuba.

The 1903 Atlantic hurricane season featured seven hurricanes, the most in an Atlantic hurricane season since 1893. The first tropical cyclone was initially observed in the western Atlantic Ocean near Puerto Rico on July 21. The tenth and final system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone well northwest of the Azores on November 25. These dates fall within the period with the most tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic. Six of the ten tropical cyclones existed simultaneously.

The 1930 Dominican Republic hurricane, also known as Hurricane San Zenón, was a small but intense and deadly tropical cyclone that severely impacted areas of the Greater Antilles, particularly the Dominican Republic, where an estimated 2,000 to 8,000 people died. The second of three known tropical cyclones in the 1930 Atlantic hurricane season, the system was first observed on August 29 to the east of the Lesser Antilles, and made landfall in the Dominican Republic at Category 4 strength on the modern Saffir-Simpson Scale. Later, it also struck Cuba and the U.S. states of Florida and North Carolina, with less severe effects.

The New Orleans Hurricane of 1915 was an intense Category 4 hurricane that made landfall near Grand Isle, Louisiana, and the most intense tropical cyclone during the 1915 Atlantic hurricane season. The storm formed in late September when it moved westward and peaked in intensity of 145 mph (233 km/h) to weaken slightly by time of landfall on September 29 with recorded wind speeds of 126 mph (203 km/h) as a strong category 3 Hurricane. The hurricane killed 275 people and caused $13 million in damage.

The 1945 Homestead hurricane, known informally as Kappler's hurricane, was the most intense tropical cyclone to strike the U.S. state of Florida since 1935. The ninth tropical storm, third hurricane, and third major hurricane of the season, it developed east-northeast of the Leeward Islands on September 12. Moving briskly west-northwestward, the storm became a major hurricane on September 13. The system moved over the Turks and Caicos Islands the following day and then Andros on September 15. Later that day, the storm peaked as a Category 4 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h). Late on September 15, the hurricane made landfall on Key Largo and then in southern Dade County, Florida.

The 1851 Atlantic hurricane season was the first Atlantic hurricane season to be included in the official Atlantic tropical cyclone record. Six known tropical cyclones occurred during the season, the earliest of which formed on June 25 and the latest of which dissipated on October 19. These dates fall within the range of most Atlantic tropical cyclone activity. None of the cyclones existed simultaneously with another. Of the six storms, three only have a single point in their track known.

The 1891 Martinique hurricane, also known as Hurricane San Magín, was an intense major hurricane that struck the island of Martinique and caused massive damage. It was the third hurricane of the 1891 Atlantic hurricane season and the only major hurricane of the season. It was first sighted east of the Lesser Antilles on August 18 as a Category 2 hurricane. The storm made landfall on the island of Martinique, where it caused severe damage, over 700 deaths and at least 1,000 injuries. It crossed eastern Dominican Republic while tracking on a northwestward direction on August 19–20, passed the Mona Passage on August 20 and the Bahamas on August 22–23. It crossed the U.S. State of Florida and dissipated in the Gulf of Mexico after August 25. Total damage is estimated at $10 million (1891 USD). The storm is considered to be the worst on Martinique since 1817.

The 1933 Trinidad hurricane was the third-farthest-east tropical storm to form in the Main Development Region (MDR) so early in the calendar year on record and was one of three North Atlantic tropical cyclones on record to produce hurricane-force winds in Venezuela. The second tropical storm and first hurricane of the extremely active 1933 Atlantic hurricane season, the system formed on June 24 to the east of the Lesser Antilles. It moved westward and attained hurricane status before striking Trinidad on June 27. The storm caused heavy damage on the island, estimated at $3 million. The strong winds downed trees and destroyed hundreds of houses, leaving about 1,000 people homeless. Later, the hurricane crossed the northeastern portion of Venezuela, where power outages and damaged houses were reported.

The 1933 Tampico hurricane was one of two storms in the 1933 Atlantic hurricane season to reach Category 5 intensity on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. It developed on September 16 near the Lesser Antilles, and slowly intensified while moving across the Caribbean Sea. Becoming a hurricane on September 19, its strengthening rate increased while passing south of Jamaica. Two days later, the hurricane reached peak winds, estimated at 160 mph (260 km/h). After weakening, it made landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula, destroying several houses. One person was killed offshore Progreso, Yucatán during the storm.

The 1903 Jamaica hurricane devastated Martinique, Jamaica, and the Cayman Islands in August 1903. The second tropical cyclone of the season, the storm was first observed well east of the Windward Islands on August 6. The system moved generally west-northwestward and strengthened into a hurricane on August 7. It struck Martinique early on August 9, shortly before reaching the Caribbean. Later that day, the storm became a major hurricane. Early on August 11, it made landfall near Morant Point, Jamaica, with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h), with would be the hurricane's maximum sustained wind speed. Early on the following day, the storm brushed Grand Cayman at the same intensity. The system weakened before landfall near Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, early on August 13, with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). The system emerging into the Gulf of Mexico early on August 14 after weakening while crossing the Yucatán Peninsula, but failed to re-strengthen. Around 00:00 UTC on August 16, the cyclone made landfall north of Tampico, Tamaulipas, with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). The hurricane soon weakened to a tropical storm and dissipated over San Luis Potosí late on August 16.

The 1944 Jamaica hurricane was a deadly major hurricane that swept across the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico in August 1944. Conservative estimates placed the storm's death toll at 116. The storm was already well-developed when it was first noted passing westward over the Windward Islands into the Caribbean Sea on August 16. A ship near Grenada with 74 occupants was lost, constituting a majority of the deaths associated with the storm. The following day, the storm intensified into a hurricane, reaching its peak strength on August 20 with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h). At this intensity, the major hurricane made landfall on Jamaica later that day, traversing the length of the island. The damage wrought was extensive, with the strong winds destroying 90 percent of banana trees and 41 percent of coconut trees in Jamaica; the overall damage toll was estimated at "several millions of dollars". The northern coast of Jamaica saw the most severe damage, with widespread structural damage and numerous homes destroyed across several parishes. In Port Maria, the storm was considered the worst since 1903.