A teratoma is a tumor made up of several different types of tissue, such as hair, muscle, teeth, or bone. Teratomata typically form in the tailbone, ovary, or testicle.

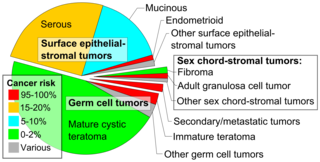

Ovarian cancer is a cancerous tumor of an ovary. It may originate from the ovary itself or more commonly from communicating nearby structures such as fallopian tubes or the inner lining of the abdomen. The ovary is made up of three different cell types including epithelial cells, germ cells, and stromal cells. When these cells become abnormal, they have the ability to divide and form tumors. These cells can also invade or spread to other parts of the body. When this process begins, there may be no or only vague symptoms. Symptoms become more noticeable as the cancer progresses. These symptoms may include bloating, vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, abdominal swelling, constipation, and loss of appetite, among others. Common areas to which the cancer may spread include the lining of the abdomen, lymph nodes, lungs, and liver.

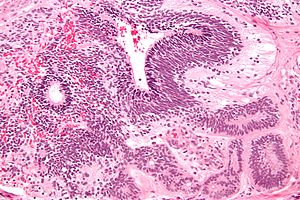

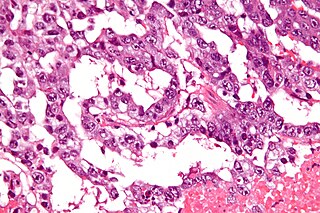

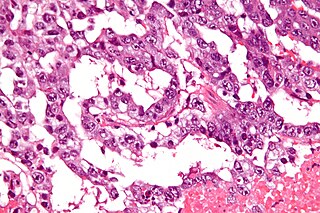

A serous tumour is a neoplasm that typically has papillary to solid formations of tumor cells with crowded nuclei, and which typically arises on the modified Mullerian-derived serous membranes that surround the ovaries in females. Such ovarian tumors are part of the surface epithelial-stromal tumour group of ovarian tumors. They are common neoplasms with a strong tendency to occur bilaterally, and they account for approximately a quarter of all ovarian tumors.

Surface epithelial-stromal tumors are a class of ovarian neoplasms that may be benign or malignant. Neoplasms in this group are thought to be derived from the ovarian surface epithelium or from ectopic endometrial or Fallopian tube (tubal) tissue. Tumors of this type are also called ovarian adenocarcinoma. This group of tumors accounts for 90% to 95% of all cases of ovarian cancer; however is mainly only found in postmenopausal women with the exception of the United States where 7% of cases occur in women under the age of 40. Serum CA-125 is often elevated but is only 50% accurate so it is not a useful tumor marker to assess the progress of treatment. 75% of women with epithelial ovarian cancer are found within the advanced-stages; however younger patients are more likely to have better prognoses than older patients.

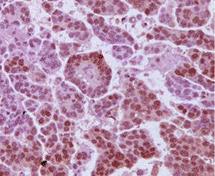

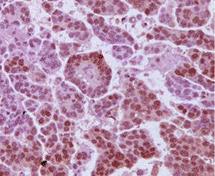

Granulosa cell tumours are tumours that arise from granulosa cells. They are estrogen secreting tumours and present as large, complex, ovarian masses. These tumours are part of the sex cord–gonadal stromal tumour or non-epithelial group of tumours. Although granulosa cells normally occur only in the ovary, granulosa cell tumours occur in both ovaries and testicles. These tumours should be considered malignant and treated in the same way as other malignant tumours of ovary. The ovarian disease has two forms, juvenile and adult, both characterized by indolent growth, and therefore has high recovery rates. The staging system for these tumours is the same as for epithelial tumours and most present as stage I. The peak age at which they occur is 50–55 years, but they may occur at any age.

Sex cord–gonadal stromal tumour is a group of tumors derived from the stromal component of the ovary and testis, which comprises the granulosa, thecal cells and fibrocytes. In contrast, the epithelial cells originate from the outer epithelial lining surrounding the gonad while the germ cell tumors arise from the precursor cells of the gametes, hence the name germ cell. In humans, this group accounts for 8% of ovarian cancers and under 5% of testicular cancers. Their diagnosis is histological: only a biopsy of the tumour can make an exact diagnosis. They are often suspected of being malignant prior to operation, being solid ovarian tumours that tend to occur most commonly in post menopausal women.

Germ cell tumor (GCT) is a neoplasm derived from germ cells. Germ-cell tumors can be cancerous or benign. Germ cells normally occur inside the gonads. GCTs that originate outside the gonads may be birth defects resulting from errors during development of the embryo.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a clinical condition caused by cancerous cells that produce abundant mucin or gelatinous ascites. The tumors cause fibrosis of tissues and impede digestion or organ function, and if left untreated, the tumors and mucin they produce will fill the abdominal cavity. This will result in compression of organs and will destroy the function of the colon, small intestine, stomach, or other organs. Prognosis with treatment in many cases is optimistic, but the disease is lethal if untreated, with death occurring via cachexia, bowel obstruction, or other types of complications.

In medicine, Meigs's syndrome, also Meigs syndrome or Demons–Meigs syndrome, is the triad of ascites, pleural effusion, and benign ovarian tumor. Meigs syndrome resolves after the resection of the tumor. Because the transdiaphragmatic lymphatic channels are larger in diameter on the right, the pleural effusion is classically on the right side. The causes of the ascites and pleural effusion are poorly understood. Atypical Meigs syndrome, characterized by a benign pelvic mass with right-sided pleural effusion but without ascites, can also occur. As in typical Meigs syndrome, pleural effusion resolves after removal of the pelvic mass.

A germinoma is a type of germ-cell tumor, which is not differentiated upon examination. It may be benign or malignant.

Ovarian tumors, or ovarian neoplasms, are tumors arising from the ovary. They can be benign or malignant. They consist of mainly solid tissue, while ovarian cysts contain fluid.

A gonadoblastoma is a complex neoplasm composed of a mixture of gonadal elements, such as large primordial germ cells, immature Sertoli cells or granulosa cells of the sex cord, and gonadal stromal cells. Gonadoblastomas are by definition benign, but more than 50% have a co-existing dysgerminoma which is malignant, and an additional 10% have other more aggressive malignancies, and as such are often treated as malignant.

Uterine clear-cell carcinoma (CC) is a rare form of endometrial cancer with distinct morphological features on pathology; it is aggressive and has high recurrence rate. Like uterine papillary serous carcinoma CC does not develop from endometrial hyperplasia and is not hormone sensitive, rather it arises from an atrophic endometrium. Such lesions belong to the type II endometrial cancers.

A borderline tumor, sometimes called low malignant potential (LMP) tumor, is a distinct but yet heterogeneous group of tumors defined by their histopathology as atypical epithelial proliferation without stromal invasion. It generally refers to such tumors in the ovary but borderline tumors may rarely occur at other locations as well.

Endodermal sinus tumor (EST) is a member of the germ cell tumor group of cancers. It is the most common testicular tumor in children under three, and is also known as infantile embryonal carcinoma. This age group has a very good prognosis. In contrast to the pure form typical of infants, adult endodermal sinus tumors are often found in combination with other kinds of germ cell tumor, particularly teratoma and embryonal carcinoma. While pure teratoma is usually benign, endodermal sinus tumor is malignant.

The ovarian fibroma, also fibroma, is a benign sex cord-stromal tumour.

Hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy (HITOC) is part of a surgical strategy employed in the treatment of various pleural malignancies. The pleura in this situation could be considered to include the surface linings of the chest wall, lungs, mediastinum, and diaphragm. HITOC is the chest counterpart of HIPEC. Traditionally used in the treatment of malignant mesothelioma, a primary malignancy of the pleura, this modality has recently been evaluated in the treatment of secondary pleural malignancies.

High-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) is a type of tumour that arises from the serous epithelial layer in the abdominopelvic cavity and is mainly found in the ovary. HGSCs make up the majority of ovarian cancer cases and have the lowest survival rates. HGSC is distinct from low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC) which arises from ovarian tissue, is less aggressive and is present in stage I ovarian cancer where tumours are localised to the ovary.

An extracranial germ cell tumor (EGCT) occurs in the abnormal growth of germ cells in the gonads and the areas other than the brain via tissue, lymphatic system, or circulatory system. The tumor can be benign or malignant (cancerous) by its growth rate. According to the National Cancer Institute and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, the chance of children who are under 15 years old having EGCTs is 3%, in comparison to adolescents, a possibility of 14% with aged 15 to 19 can have EGCTs. There is no obvious cut point in between children and adolescents. However, common cut points in researches are 11 years old and 15 years old.

Ovarian germ cell tumors (OGCTs) are heterogeneous tumors that are derived from the primitive germ cells of the embryonic gonad, which accounts for about 2.6% of all ovarian malignancies. There are four main types of OGCTs, namely dysgerminomas, yolk sac tumor, teratoma, and choriocarcinoma.