A small proportion of humans show partial or apparently complete innate resistance to HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. [1] The main mechanism is a mutation of the gene encoding CCR5, which acts as a co-receptor for HIV. It is estimated that the proportion of people with some form of resistance to HIV is under 10%. [2]

In 1994, Stephen Crohn became the first person discovered to be completely resistant to HIV in all tests performed despite having partners infected by the virus. [3] Crohn's resistance was a result of the absence of a receptor, which prevent the HIV from infecting CD4 present on the exterior of the white blood cells. The absence of such receptors, or rather the shortening of them to the point of being inoperable, is known as the delta 32 mutation. [4] This mutation is linked to groups of people that have been exposed to HIV but remain uninfected such as some offspring of HIV positive mothers, health officials, and sex workers. [5]

In early 2000, researchers discovered a small group of sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya, who were estimated to have sexual contact with 60 to 70 HIV positive clients a year without signs of infection. [6] These sex workers were not found to have the delta mutation leading scientists to believe other factors could create a genetic resistance to HIV. [5] Researchers from Public Health Agency of Canada have identified 15 proteins unique to those virus-free sex workers. [7] Later, however, some sex workers were discovered to have contracted the virus, leading Oxford University researcher Sarah Rowland-Jones to believe continual exposure is a requirement for maintaining immunity. [8] [9]

C-C chemokine receptor type 5, also known as CCR5 or CD195, is a protein on the surface of white blood cells that is involved in the immune system as it acts as a receptor for chemokines. This is the process by which T cells are attracted to specific tissue and organ targets. Many strains of HIV use CCR5 as a co-receptor to enter and infect host cells. A few individuals carry a mutation known as CCR5-Δ32 in the CCR5 gene, protecting them against these strains of HIV.[ citation needed ]

In humans, the CCR5 gene that encodes the CCR5 protein is located on the short (p) arm at position 21 on chromosome 3. A cohort study, from June 1981 to October 2016, looked into the correlation between the delta 32 deletion and HIV resistance, and found that homozygous carriers of the delta 32 mutation are resistant to M-tropic strains of HIV-1 infection. [10] Certain populations have inherited the Delta 32 mutation resulting in the genetic deletion of a portion of the CCR5 gene. [11] [ excessive citations ]

In 2019, it was discovered that a mutation of TNPO3 that causes type 1F limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD1F) also causes innate resistance to HIV-1. [12] TNP03 was known to be involved into virus transportation into the infected cells. Blood samples from a family affected by LGMD1F showed a resistance to HIV infection. While the CCR5Δ32 deletion blocks the entry of virus strains that use the CCR5 receptor, the TNPO3 mutation causing LGMD1F blocks the CXCR4 receptor, making it effective on different HIV-1 strains, due to HIV tropism.[ citation needed ]

Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) provide a protective reaction against HIV when consistent exposure to the virus is present. The Nairobi sex workers were found to have these CTLs within genital mucus, preventing the spread of HIV within heterosexual transmission. While creating a protective seal, CTLs become ineffective when lapses in HIV exposure occur, which leads to the possibility of CTLs only being an indicator of other genetic resistances towards HIV, such as immunoglobulin A responses within vaginal fluids. [5] [13]

Chimpanzees in African countries have been found to develop AIDS at a slower rate than humans. This resistance is not due to the primate's ability to control the virus in a manner that is substantially more effective than humans, but rather because of the lack of tissues created within the body that typically progress HIV to AIDS. The chimpanzees also lack CD4 T cells and immune activation that is required for the spread of HIV. [13]

While antiretroviral therapy (ART) has slowed the progression of HIV among patients, gene therapy through stem cell research gave resistance to HIV. One method of genetic modification is through the manipulation of hematopoietic stem cells, which replaces HIV genes with engineered particles that attach to chromosomes. Peptides are formed that prevent HIV from fusing to the host cells and therefore stops the infection from spreading. Another method used by the Kiem lab was the release of zinc finger nuclease (ZFN), which identifies specific sections of DNA to cause a break in the double helix. These ZFNs were used to target CCR5 in order to delete the protein, halting the course of the infection. [14]

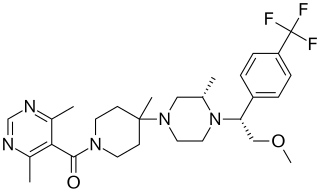

Alternatively to gene therapy, medication such as maraviroc (MVC) is being used to bind with CCR5 particles, blocking the entry of HIV into the cell. While not effective with all types, MVC has been proven to decrease the spread of HIV through monotherapy as well as combination therapy with ARTs. MVC is the only CCR5 binding drug approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration, the European Commission and Health Canada. [15]

While the delta mutation has been observed to prevent HIV in specific populations, it has shown little to no effect between healthy individuals and those who are infected with HIV among Iranian populations. This is attributed to individuals being heterozygous for the mutation, which prevents the delta mutation from effectively prohibiting HIV from entering immune cells. [16]

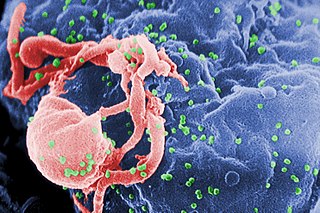

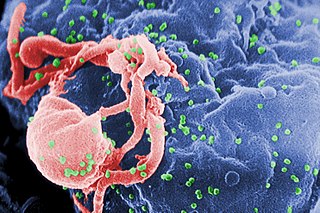

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of Lentivirus that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the immune system allows life-threatening opportunistic infections and cancers to thrive. Without treatment, average survival time after infection with HIV is estimated to be 9 to 11 years, depending on the HIV subtype.

Antiviral drugs are a class of medication used for treating viral infections. Most antivirals target specific viruses, while a broad-spectrum antiviral is effective against a wide range of viruses. Antiviral drugs are one class of antimicrobials, a larger group which also includes antibiotic, antifungal and antiparasitic drugs, or antiviral drugs based on monoclonal antibodies. Most antivirals are considered relatively harmless to the host, and therefore can be used to treat infections. They should be distinguished from virucides, which are not medication but deactivate or destroy virus particles, either inside or outside the body. Natural virucides are produced by some plants such as eucalyptus and Australian tea trees.

The management of HIV/AIDS normally includes the use of multiple antiretroviral drugs as a strategy to control HIV infection. There are several classes of antiretroviral agents that act on different stages of the HIV life-cycle. The use of multiple drugs that act on different viral targets is known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). HAART decreases the patient's total burden of HIV, maintains function of the immune system, and prevents opportunistic infections that often lead to death. HAART also prevents the transmission of HIV between serodiscordant same-sex and opposite-sex partners so long as the HIV-positive partner maintains an undetectable viral load.

Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) is a species of retrovirus that cause persistent infections in at least 45 species of non-human primates. Based on analysis of strains found in four species of monkeys from Bioko Island, which was isolated from the mainland by rising sea levels about 11,000 years ago, it has been concluded that SIV has been present in monkeys and apes for at least 32,000 years, and probably much longer.

C-C chemokine receptor type 5, also known as CCR5 or CD195, is a protein on the surface of white blood cells that is involved in the immune system as it acts as a receptor for chemokines.

Viral pathogenesis is the study of the process and mechanisms by which viruses cause diseases in their target hosts, often at the cellular or molecular level. It is a specialized field of study in virology.

Following infection with HIV-1, the rate of clinical disease progression varies between individuals. Factors such as host susceptibility, genetics and immune function, health care and co-infections as well as viral genetic variability may affect the rate of progression to the point of needing to take medication in order not to develop AIDS.

A co-receptor is a cell surface receptor that binds a signalling molecule in addition to a primary receptor in order to facilitate ligand recognition and initiate biological processes, such as entry of a pathogen into a host cell.

Antigenic variation or antigenic alteration refers to the mechanism by which an infectious agent such as a protozoan, bacterium or virus alters the proteins or carbohydrates on its surface and thus avoids a host immune response, making it one of the mechanisms of antigenic escape. It is related to phase variation. Antigenic variation not only enables the pathogen to avoid the immune response in its current host, but also allows re-infection of previously infected hosts. Immunity to re-infection is based on recognition of the antigens carried by the pathogen, which are "remembered" by the acquired immune response. If the pathogen's dominant antigen can be altered, the pathogen can then evade the host's acquired immune system. Antigenic variation can occur by altering a variety of surface molecules including proteins and carbohydrates. Antigenic variation can result from gene conversion, site-specific DNA inversions, hypermutation, or recombination of sequence cassettes. The result is that even a clonal population of pathogens expresses a heterogeneous phenotype. Many of the proteins known to show antigenic or phase variation are related to virulence.

Entry inhibitors, also known as fusion inhibitors, are a class of antiviral drugs that prevent a virus from entering a cell, for example, by blocking a receptor. Entry inhibitors are used to treat conditions such as HIV and hepatitis D.

Chemokine receptors are cytokine receptors found on the surface of certain cells that interact with a type of cytokine called a chemokine. There have been 20 distinct chemokine receptors discovered in humans. Each has a rhodopsin-like 7-transmembrane (7TM) structure and couples to G-protein for signal transduction within a cell, making them members of a large protein family of G protein-coupled receptors. Following interaction with their specific chemokine ligands, chemokine receptors trigger a flux in intracellular calcium (Ca2+) ions (calcium signaling). This causes cell responses, including the onset of a process known as chemotaxis that traffics the cell to a desired location within the organism. Chemokine receptors are divided into different families, CXC chemokine receptors, CC chemokine receptors, CX3C chemokine receptors and XC chemokine receptors that correspond to the 4 distinct subfamilies of chemokines they bind. Four families of chemokine receptors differ in spacing of cysteine residues near N-terminal of the receptor.

A resistance mutation is a mutation in a virus gene that allows the virus to become resistant to treatment with a particular antiviral drug. The term was first used in the management of HIV, the first virus in which genome sequencing was routinely used to look for drug resistance. At the time of infection, a virus will infect and begin to replicate within a preliminary cell. As subsequent cells are infected, random mutations will occur in the viral genome. When these mutations begin to accumulate, antiviral methods will kill the wild type strain, but will not be able to kill one or many mutated forms of the original virus. At this point a resistance mutation has occurred because the new strain of virus is now resistant to the antiviral treatment that would have killed the original virus. Resistance mutations are evident and widely studied in HIV due to its high rate of mutation and prevalence in the general population. Resistance mutation is now studied in bacteriology and parasitology.

Vicriviroc, previously named SCH 417690 and SCH-D, is a pyrimidine CCR5 entry inhibitor of HIV-1. It was developed by the pharmaceutical company Schering-Plough. Merck decided to not pursue regulatory approval for use in treatment-experienced patients because the drug did not meet primary efficacy endpoints in late stage trials. Clinical trials continue in patients previously untreated for HIV.

CD4 immunoadhesin is a recombinant fusion protein consisting of a combination of CD4 and the fragment crystallizable region, similarly known as immunoglobulin. It belongs to the antibody (Ig) gene family. CD4 is a surface receptor for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The CD4 immunoadhesin molecular fusion allow the protein to possess key functions from each independent subunit. The CD4 specific properties include the gp120-binding and HIV-blocking capabilities. Properties specific to immunoglobulin are the long plasma half-life and Fc receptor binding. The properties of the protein means that it has potential to be used in AIDS therapy as of 2017. Specifically, CD4 immunoadhesin plays a role in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) towards HIV-infected cells. While natural anti-gp120 antibodies exhibit a response towards uninfected CD4-expressing cells that have a soluble gp120 bound to the CD4 on the cell surface, CD4 immunoadhesin, however, will not exhibit a response. One of the most relevant of these possibilities is its ability to cross the placenta.

Long-term nonprogressors (LTNPs), sometimes also called elite controllers, are individuals infected with HIV, who maintain a CD4 count greater than 500 without antiretroviral therapy with a detectable viral load. Many of these patients have been HIV positive for 30 years without progressing to the point of needing to take medication in order not to develop AIDS. They have been the subject of a great deal of research, since an understanding of their ability to control HIV infection may lead to the development of immune therapies or a therapeutic vaccine. The classification "Long-term non-progressor" is not permanent, because some patients in this category have gone on to develop AIDS.

Gero Hütter is a German hematologist. Hütter and his medical team transplanted bone marrow deficient in a key HIV receptor to a leukemia patient, Timothy Ray Brown, who was also infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Subsequently, the patient's circulating HIV dropped to undetectable levels. The case was widely reported in the media, and Hütter was named one of the "Berliners of the year" for 2008 by the Berliner Morgenpost, a Berlin newspaper.

CCR5 receptor antagonists are a class of small molecules that antagonize the CCR5 receptor. The C-C motif chemokine receptor CCR5 is involved in the process by which HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, enters cells. Hence antagonists of this receptor are entry inhibitors and have potential therapeutic applications in the treatment of HIV infections.

The Berlin patient is an anonymous person from Berlin, Germany, who was described in 1998 as exhibiting prolonged "post-treatment control" of HIV viral load after HIV treatments were interrupted.

HIV/AIDS research includes all medical research that attempts to prevent, treat, or cure HIV/AIDS, as well as fundamental research about the nature of HIV as an infectious agent and AIDS as the disease caused by HIV.

Since antiretroviral therapy requires a lifelong treatment regimen, research to find more permanent cures for HIV infection is currently underway. It is possible to synthesize zinc finger nucleotides with zinc finger components that selectively bind to specific portions of DNA. Conceptually, targeting and editing could focus on host cellular co-receptors for HIV or on proviral HIV DNA.

Public Health Agency of Canada have identified 15 proteins unique to those virus-free prostitutes