Lillooet is a district municipality in the Squamish-Lillooet region of southwestern British Columbia. The town is on the west shore of the Fraser River immediately north of the Seton River mouth. On BC Highway 99, the locality is by road about 100 kilometres (62 mi) northeast of Pemberton, 64 kilometres (40 mi) northwest of Lytton, and 172 kilometres (107 mi) west of Kamloops.

The Stʼatʼimc, also known as the Lillooet, St̓át̓imc, Stl'atl'imx, etc., are an Interior Salish people located in the southern Coast Mountains and Fraser Canyon region of the Interior of the Canadian province of British Columbia.

Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Plateau, also referred to by the phrase Indigenous peoples of the Plateau, and historically called the Plateau Indians are Indigenous peoples of the Interior of British Columbia, Canada, and the non-coastal regions of the Northwestern United States.

The Fraser Canyon is a major landform of the Fraser River where it descends rapidly through narrow rock gorges in the Coast Mountains en route from the Interior Plateau of British Columbia to the Fraser Valley. Colloquially, the term "Fraser Canyon" is often used to include the Thompson Canyon from Lytton to Ashcroft, since they form the same highway route which most people are familiar with, although it is actually reckoned to begin above Williams Lake at Soda Creek Canyon near the town of the same name.

A pit-house is a house built in the ground and used for shelter. Besides providing shelter from the most extreme of weather conditions, this type of earth shelter may also be used to store food and for cultural activities like the telling of stories, dancing, singing and celebrations. General dictionaries also describe a pit-house as a dugout, and it has similarities to a half-dugout.

Marble Canyon is in the south-central Interior of British Columbia, a few kilometres east of the Fraser River and the community of Pavilion, midway between the towns of Lillooet and Cache Creek. The canyon stems from a collapsed karst formation.

The Interior Plateau comprises a large region of the Interior of British Columbia, and lies between the Cariboo and Monashee Mountains on the east, and the Hazelton Mountains, Coast Mountains and Cascade Range on the west. The continuation of the plateau into the United States is known there as the Columbia Plateau.

The Camelsfoot Range is a sub-range of the Chilcotin Ranges subdivision of the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains in British Columbia. The Fraser River forms its eastern boundary. The range is approximately 90 km at its maximum length and less than 30 km wide at its widest.

A quiggly hole, also known as a pit-house or simply as a quiggly or kekuli, is the remains of an earth lodge built by the First Nations people of the Interior of British Columbia and the Columbia Plateau in the United States. The word quiggly comes from a mispronunciation of the nsyilxcǝn term qʷc̓iʔ, which was incorporated into Chinook Jargon as kickwillie. Kick willy, kickwillie, or keekwulee are the spelling variations of the Chinook Jargon word for "beneath" or "under".

N'Quatqua, variously spelled Nequatque, N'quat'qua, is the proper historic name in the St'at'imcets language for the First Nations village of the Stl'atl'imx people of the community of D'Arcy, which is at the upper end of Anderson Lake about 35 miles southeast of Lillooet and about the same distance from Pemberton. The usage is synonymous with Nequatque Indian Reserve No. 1, which is 177 ha. in size and located adjacent to the mouth of the Gates River.

Oshara Tradition, the northern tradition of the earlier Picosa culture, was a Southwestern Archaic tradition centered in the area now called New Mexico and Colorado. Cynthia Irwin-Williams developed the sequence of Archaic culture for Oshara during her work in the Arroyo Cuervo area of northwestern New Mexico. Irwin contends that the Ancestral Puebloans developed, at least in part, from the Oshara.

Fountain is an unincorporated rural area and Indian reserve community in the Fraser Canyon region of British Columbia, Canada, located at the ten-mile (16 km) mark from the town of Lillooet on BC Highway 99, which in that area is also on the route of the Old Cariboo Road and is located at the junction of that route with the old gold rush-era trail via Fountain Valley and the Fountain Lakes.

The Hoko River Archeological Site complex, located in Clallam County in the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Washington, is a 2,500-year-old fishing camp. Hydraulic excavation methods, which were first developed on the site, and artifacts found there have contributed to the understanding of the traditions and culture of the Makah people who have inhabited the northwest for 3,800 years. The site has also shed light on the evolution of food storage and the flora and fauna that existed in the area around 2500 B.P. Its name comes from the Hoko River.

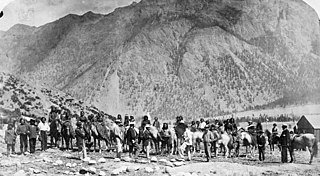

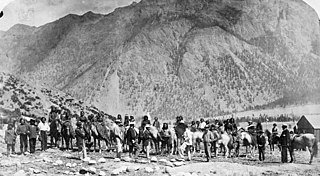

The Bridge River Rapids, also known as the Six Mile Rapids, the Lower Fountain, the Bridge River Fishing Grounds, and in the St'at'imcets language as Sat' or Setl, is a set of rapids on the Fraser River, located in the central Fraser Canyon at the mouth of the Bridge River six miles north of the confluence of Cayoosh Creek with the Fraser and on the northern outskirts of the District of Lillooet, British Columbia, Canada.

Jeanne E. Arnold was an American archaeologist who taught in the anthropology department at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her fields of research covered many topics, but she specialized in the prehistoric and early contact era of the Pacific Coast of North America, in California and British Columbia. Her work in these areas was directed to resolving the economies and political evolutionary trajectories of complex hunter-gatherer groups. She died on November 27, 2022, following a long illness.

The Basketmaker III Era also called the "Modified Basketmaker" period, was the third period in which Ancient Pueblo People were cultivating food, began making pottery and living in more sophisticated clusters of pit-house dwellings. Hunting was easier with the adoption of the bow and arrow.

Keatley Creek is a left tributary of the Fraser River in the Glen Valley area of the Fraser Canyon in the Interior of British Columbia, Canada. Its outlet into the Fraser is between those of Pavilion and Fountain Creeks, approximately 16 miles upstream from the town of Lillooet; the next tributary southwards is the larger Sallus Creek.

Texas Creek is a medium-sized right tributary of the Fraser River in the Fraser Canyon region of that river's course, located approximately 16 miles down the river from the town of Lillooet. Texas Creek is also the name of the rural neighbourhood in the area of the creek, and also that of the Texas Creek Ranch which is one of the larger holdings.

Glen Fraser is a locality in the central Fraser Canyon of the Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada, located c. 18 miles north of the town of Lillooet and between the communities of Fountain (S) and Pavilion. It is a ranching area formed of benchlands on the west side of the Fraser and is the location of the Keatley Creek Archaeological Site, one of Canada's most important ongoing investigations. The name was conferred as that of a railway stop on the Pacific Great Eastern Railway, now Canadian National.

Whittlesey culture is an archaeological designation for a Native American people, who lived in northeastern Ohio during the Late Precontact and Early Contact period between A.D. 1000 to 1640. By 1500, they flourished as an agrarian society that grew maize, beans, and squash. After European contact, their population decreased due to disease, malnutrition, and warfare. There was a period of long, cold winters that would have impacted their success cultivating food from about 1500.