Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Mali face legal and societal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Although same-sex sexual activity is not illegal in Mali, LGBT people face widespread discrimination among the broader population. According to the 2007 Pew Global Attitudes Project, 98 percent of Malian adults believed that homosexuality is considered something society should not accept, which was the highest rate of non-acceptance in the 45 countries surveyed.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Ghana face legal and societal challenges and discrimination not experienced by non-LGBT citizens.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people in the United Arab Emirates face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Homosexuality is illegal in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and under the federal criminal provisions, consensual same-sex sexual activity is punishable by imprisonment; extra-marital sexual activity between persons of different sexes is also illegal. In both cases, prosecution will only be brought if a husband or male guardian of one of the participants makes a criminal complaint. The penalty is a minimum of six months imprisonment; no maximum penalty is prescribed, and the court has full discretion to impose any sentence in accordance with the country's constitution.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Albania face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents, although LGBT people are protected under comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation. Both male and female same-gender sexual activities have been legal in Albania since 1995, but households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-gender couples, with same-sex unions not being recognized in the country in any form.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Armenia face legal and social challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents, due in part to the lack of laws prohibiting discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity and in part to prevailing negative attitudes about LGBT persons throughout society.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Ethiopia face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are illegal in the country, with reports of high levels of discrimination and abuses against LGBT people. Ethiopia has a long history of social conservatism and same-sex sexual activity is considered a social taboo.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Algeria face legal challenges and discrimination not experienced by non-LGBT residents. According to the International Lesbian and Gay Association's May 2008 report, both male and female same-sex sexual acts are illegal in Algeria. Homophobic attitudes are normalised within Algerian society, and LGBT people are commonly subjected to discrimination and potential arrest.

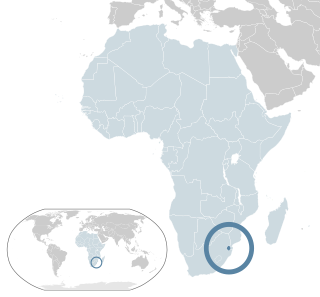

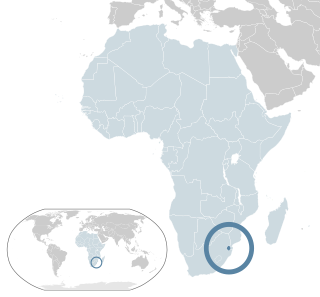

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Cape Verde are afforded greater protections than those in many other African countries. Homosexual activity has been legal in Cape Verde since 2004. Additionally, since 2008, employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation has been banned, making Cape Verde one of the few African countries to have such protections for LGBT people. Nevertheless, Cape Verde does not recognize same-sex unions or marriages, meaning that same-sex couples may still face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Households headed by same-sex couples are also not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Sudan face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity in Sudan is illegal for both men and women, while homophobic attitudes remain ingrained throughout the nation.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Gambia face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both males and females in the Gambia. Criminalisation commenced under the colonial rule of the British. The 1933 Criminal Code provides penalties of prison terms of up to fourteen years. In 2014, the country amended its code to impose even harsher penalties of life imprisonment for "aggravated" cases. While the United States Department of State reports that the laws against homosexual activity are not "actively enforced", arrests have occurred; the NGO Human Rights Watch, reports regular organised actions by law enforcement against persons suspected of homosexuality and gender non-conformity.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Brunei face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female expressions of homosexuality are illegal in Brunei. Sexual activity between men is de jure liable to capital punishment, with de facto lesser penalties of imprisonment and whipping applied; sex between women is punishable by caning or imprisonment. The sultanate applied a moratorium on the death penalty in 2019, which was still in effect as at May 2023. The moratorium could be revoked at any time.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Mauritania face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female kinds of same-sex sexual activity are illegal in Mauritania. Openly homosexual Muslim men face stoning to death, though there have been no known cases of executions caused by homosexuality charges in the country; whereas women who have sex with women face prison.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Somalia face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Consensual same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both men and women. In areas controlled by al-Shabab, and in Jubaland, capital punishment is imposed for such sexual activity. In other areas, where Sharia does not apply, the civil law code specifies prison sentences of up to three years as penalty. LGBT people are regularly prosecuted by the government and additionally face stigmatization among the broader population. Stigmatization and criminalisation of homosexuality in Somalia occur in a legal and cultural context where 99% of the population follow Islam as their religion, while the country has had an unstable government and has been subjected to a civil war for decades.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Eswatini have limited legal rights. According to Rock of Hope, a Swati LGBT advocacy group, "there is no legislation recognising LGBTIs or protecting the right to a non-heterosexual orientation and gender identity and as a result [LGBT people] cannot be open about their orientation or gender identity for fear of rejection and discrimination". Homosexuality is illegal in Eswatini, though this law is in practice unenforced. According to the 2021 Human Rights Practices Report from the US Department of State, "there has never been an arrest or prosecution for consensual same-sex conduct."

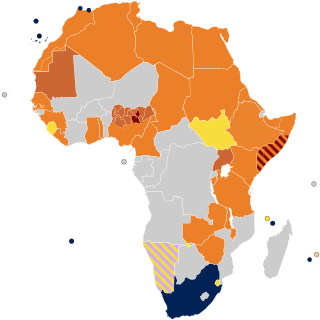

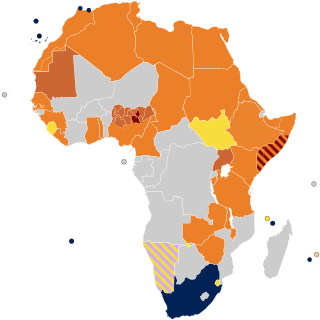

With the exceptions of some countries in Africa like South Africa, Cape Verde, Mauritius, Seychelles, Angola, Botswana, and Mozambique, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Africa are limited in comparison to the Americas, Western Europe and Oceania.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Zambia face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both males and females in Zambia. Formerly a colony of the British Empire, Zambia inherited the laws and legal system of its colonial occupiers upon independence in 1964. Laws concerning homosexuality have largely remained unchanged since then, and homosexuality is covered by sodomy laws that also proscribe bestiality. Social attitudes toward LGBT people are mostly negative and coloured by perceptions that homosexuality is immoral and a form of insanity. However, in recent years, younger generations are beginning to show positive and open minded attitudes towards their LGBT peers.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Equatorial Guinea face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female kinds of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Equatorial Guinea, however LGBT persons face stigmatization among the broader population, and same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available as opposite-sex couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Mozambique face legal challenges not faced by non-LGBT people. Same-sex sexual activity became legal in Mozambique under the new Criminal Code that took effect in June 2015. Discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment has been illegal since 2007.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in South Sudan face legal and societal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Male same-sex sexual activity is illegal and carries a penalty of up to ten years' imprisonment. Active enforcement of the law is not pursued by authorities: No prosecutions are known to have occurred since South Sudan gained its independence in 2011. LGBT persons are met with abuse and discrimination from agents of the government and additionally face stigmatisation among the broader population.

Capital punishment as a criminal punishment for homosexuality has been implemented by a number of countries in their history. It currently remains a legal punishment in several countries and regions, most of which have sharia–based criminal laws except for Uganda.