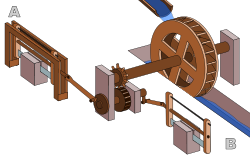

A crankshaft is a mechanical component used in a piston engine to convert the reciprocating motion into rotational motion. The crankshaft is a rotating shaft containing one or more crankpins, that are driven by the pistons via the connecting rods.

Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical ancient Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often considered one body of classical architecture. Roman architecture flourished in the Roman Republic and to an even greater extent under the Empire, when the great majority of surviving buildings were constructed. It used new materials, particularly Roman concrete, and newer technologies such as the arch and the dome to make buildings that were typically strong and well engineered. Large numbers remain in some form across the former empire, sometimes complete and still in use today.

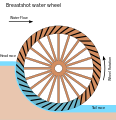

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in the production of many material goods, including flour, lumber, paper, textiles, and many metal products. These watermills may comprise gristmills, sawmills, paper mills, textile mills, hammermills, trip hammering mills, rolling mills, wire drawing mills.

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel, with a number of blades or buckets arranged on the outside rim forming the driving car. Water wheels were still in commercial use well into the 20th century but they are no longer in common use. Uses included milling flour in gristmills, grinding wood into pulp for papermaking, hammering wrought iron, machining, ore crushing and pounding fibre for use in the manufacture of cloth.

A sawmill or lumber mill is a facility where logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes. The "portable" sawmill is simple to operate. The log lies flat on a steel bed, and the motorized saw cuts the log horizontally along the length of the bed, by the operator manually pushing the saw. The most basic kind of sawmill consists of a chainsaw and a customized jig, with similar horizontal operation.

A noria is a hydropowered scoop wheel used to lift water into a small aqueduct, either for the purpose of irrigation or to supply water to cities and villages.

A crank is an arm attached at a right angle to a rotating shaft by which circular motion is imparted to or received from the shaft. When combined with a connecting rod, it can be used to convert circular motion into reciprocating motion, or vice versa. The arm may be a bent portion of the shaft, or a separate arm or disk attached to it. Attached to the end of the crank by a pivot is a rod, usually called a connecting rod (conrod).

A trip hammer, also known as a tilt hammer or helve hammer, is a massive powered hammer. Traditional uses of trip hammers include pounding, decorticating and polishing of grain in agriculture. In mining, trip hammers were used for crushing metal ores into small pieces, although a stamp mill was more usual for this. In finery forges they were used for drawing out blooms made from wrought iron into more workable bar iron. They were also used for fabricating various articles of wrought iron, latten, steel and other metals.

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east, but transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. The architecture used in Rome was strongly influenced by Greek and Etruscan sources.

Renaissance technology was the set of European artifacts and inventions which spread through the Renaissance period, roughly the 14th century through the 16th century. The era is marked by profound technical advancements such as the printing press, linear perspective in drawing, patent law, double shell domes and bastion fortresses. Sketchbooks from artisans of the period give a deep insight into the mechanical technology then known and applied.

Antipater of Thessalonica was a Greek epigrammatist of the Roman period.

The Arab Agricultural Revolution was the transformation in agriculture in the Old World during the Islamic Golden Age. The agronomic literature of the time, with major books by Ibn Bassal and Abū l-Khayr al-Ishbīlī, demonstrates the extensive diffusion of useful plants to Medieval Spain (al-Andalus), and the growth in Islamic scientific knowledge of agriculture and horticulture. Medieval Arab historians and geographers described al-Andalus as a fertile and prosperous region with abundant water, full of fruit from trees such as the olive and pomegranate. Archaeological evidence demonstrates improvements in animal husbandry and in irrigation such as with the saqiyah waterwheel. These changes made agriculture far more productive, supporting population growth, urbanisation, and increased stratification of society.

Ancient Greek technology developed during the 5th century BC, continuing up to and including the Roman period, and beyond. Inventions that are credited to the ancient Greeks include the gear, screw, rotary mills, bronze casting techniques, water clock, water organ, the torsion catapult, the use of steam to operate some experimental machines and toys, and a chart to find prime numbers. Many of these inventions occurred late in the Greek period, often inspired by the need to improve weapons and tactics in war. However, peaceful uses are shown by their early development of the watermill, a device which pointed to further exploitation on a large scale under the Romans. They developed surveying and mathematics to an advanced state, and many of their technical advances were published by philosophers, like Archimedes and Heron.

Roman technology is the collection of antiques, skills, methods, processes, and engineering practices which supported Roman civilization and made possible the expansion of the economy and military of ancient Rome.

A ship mill, more commonly known as a boat mill, is a type of watermill. The milling and grinding technology and the drive (waterwheel) are built on a floating platform on this type of mill. Its first recorded use dates back to mid-6th century AD Italy.

The Hierapolis sawmill was a Roman water-powered stone sawmill at Hierapolis, Asia Minor. Dating to the second half of the 3rd century AD, the sawmill is considered the earliest known machine to combine a crank with a connecting rod to form a crank slider mechanism.

A gristmill grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separated from its chaff in preparation for grinding.

Örjan Wikander is a Swedish classical archaeologist and ancient historian. His main interests are ancient water technology, ancient roof terracottas, Roman social history, Etruscan archaeology and epigraphy.