A crankshaft is a mechanical component used in a piston engine to convert the reciprocating motion into rotational motion. The crankshaft is a rotating shaft containing one or more crankpins, that are driven by the pistons via the connecting rods.

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is typically a heat engine that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert high temperature and high pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common features of all types. The main types are: the internal combustion engine, used extensively in motor vehicles; the steam engine, the mainstay of the Industrial Revolution; and the Stirling engine for niche applications. Internal combustion engines are further classified in two ways: either a spark-ignition (SI) engine, where the spark plug initiates the combustion; or a compression-ignition (CI) engine, where the air within the cylinder is compressed, thus heating it, so that the heated air ignites fuel that is injected then or earlier.

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be transformed, by a connecting rod and crank, into rotational force for work. The term "steam engine" is most commonly applied to reciprocating engines as just described, although some authorities have also referred to the steam turbine and devices such as Hero's aeolipile as "steam engines." The essential feature of steam engines is that they are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separated from the combustion products. The ideal thermodynamic cycle used to analyze this process is called the Rankine cycle. In general usage, the term steam engine can refer to either complete steam plants, such as railway steam locomotives and portable engines, or may refer to the piston or turbine machinery alone, as in the beam engine and stationary steam engine.

Decimius Magnus Ausonius was a Roman poet and teacher of rhetoric from Burdigala, Aquitaine. For a time, he was tutor to the future Emperor Gratian, who afterwards bestowed the consulship on him. His best-known poems are Mosella, a description of the River Moselle, and Ephemeris, an account of a typical day in his life. His many other verses show his concern for his family, friends, teachers and circle of well-to-do acquaintances and his delight in the technical handling of meter.

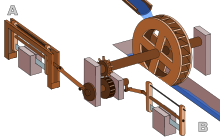

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in the production of many material goods, including flour, lumber, paper, textiles, and many metal products. These watermills may comprise gristmills, sawmills, paper mills, textile mills, hammermills, trip hammering mills, rolling mills, wire drawing mills.

Badīʿ az-Zaman Abu l-ʿIzz ibn Ismāʿīl ibn ar-Razāz al-Jazarī was a Muslim polymath: a scholar, inventor, mechanical engineer, artisan, artist and mathematician from the Artuqid Dynasty of Jazira in Mesopotamia. He is best known for writing The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices in 1206, where he described 50 mechanical devices, along with instructions on how to construct them. He is credited with the invention of the elephant clock. He has been described as the "father of robotics" and modern day engineering.

A sawmill or lumber mill is a facility where logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes. The "portable" sawmill is simple to operate. The log lies flat on a steel bed, and the motorized saw cuts the log horizontally along the length of the bed, by the operator manually pushing the saw. The most basic kind of sawmill consists of a chainsaw and a customized jig, with similar horizontal operation.

A connecting rod, also called a 'con rod', is the part of a piston engine which connects the piston to the crankshaft. Together with the crank, the connecting rod converts the reciprocating motion of the piston into the rotation of the crankshaft. The connecting rod is required to transmit the compressive and tensile forces from the piston. In its most common form, in an internal combustion engine, it allows pivoting on the piston end and rotation on the shaft end.

In mechanical engineering, an eccentric is a circular disk solidly fixed to a rotating axle with its centre offset from that of the axle.

Quern-stones are stone tools for hand-grinding a wide variety of materials, especially for various types of grains. They are used in pairs. The lower stationary stone of early examples is called a saddle quern, while the upper mobile stone is called a muller, rubber, or handstone. The upper stone was moved in a back-and-forth motion across the saddle quern. Later querns are known as rotary querns. The central hole of a rotary quern is called the eye, and a dish in the upper surface is known as the hopper. A handle slot contained a handle which enabled the rotary quern to be rotated. They were first used in the Neolithic era to grind cereals into flour.

Reciprocating motion, also called reciprocation, is a repetitive up-and-down or back-and-forth linear motion. It is found in a wide range of mechanisms, including reciprocating engines and pumps. The two opposite motions that comprise a single reciprocation cycle are called strokes.

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east, but transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. The architecture used in Rome was strongly influenced by Greek and Etruscan sources.

Renaissance technology was the set of European artifacts and inventions which spread through the Renaissance period, roughly the 14th century through the 16th century. The era is marked by profound technical advancements such as the printing press, linear perspective in drawing, patent law, double shell domes and bastion fortresses. Sketchbooks from artisans of the period give a deep insight into the mechanical technology then known and applied.

A reciprocating pump is a class of positive-displacement pumps that includes the piston pump, plunger pump, and diaphragm pump. Well maintained, reciprocating pumps can last for decades. Unmaintained, however, they can succumb to wear and tear. It is often used where a relatively small quantity of liquid is to be handled and where delivery pressure is quite large. In reciprocating pumps, the chamber that traps the liquid is a stationary cylinder that contains a piston or plunger.

A marine steam engine is a steam engine that is used to power a ship or boat. This article deals mainly with marine steam engines of the reciprocating type, which were in use from the inception of the steamboat in the early 19th century to their last years of large-scale manufacture during World War II. Reciprocating steam engines were progressively replaced in marine applications during the 20th century by steam turbines and marine diesel engines.

The Hierapolis sawmill was a Roman water-powered stone sawmill at Hierapolis, Asia Minor. Dating to the second half of the 3rd century AD, the sawmill is considered the earliest known machine to combine a crank with a connecting rod to form a crank slider mechanism.

An internal combustion engine is a heat engine in which the combustion of a fuel occurs with an oxidizer in a combustion chamber that is an integral part of the working fluid flow circuit. In an internal combustion engine, the expansion of the high-temperature and high-pressure gases produced by combustion applies direct force to some component of the engine. The force is typically applied to pistons, turbine blades, a rotor, or a nozzle. This force moves the component over a distance, transforming chemical energy into kinetic energy which is used to propel, move or power whatever the engine is attached to.

The Lap Engine is a beam engine designed by James Watt, built by Boulton and Watt in 1788. It is now preserved at the Science Museum, London.