The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revolution. Inspired by Enlightenment philosophers, the Declaration was a core statement of the values of the French Revolution and had a significant impact on the development of popular conceptions of individual liberty and democracy in Europe and worldwide.

The French Revolution was a period of political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789, and ended with the coup of 18 Brumaire on November 1799 and the formation of the French Consulate. Many of its ideas are considered fundamental principles of liberal democracy, while its values and institutions remain central to modern French political discourse.

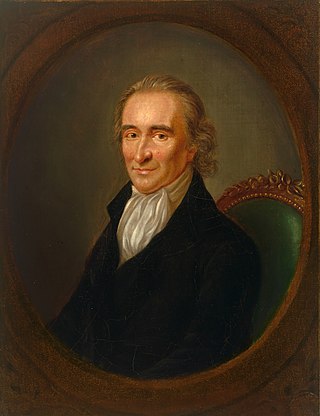

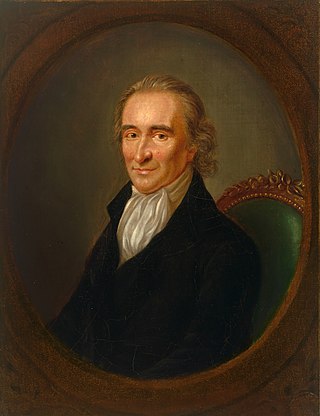

Thomas Paine was an English-born American Founding Father, political activist, philosopher, political theorist, and revolutionary. He authored Common Sense (1776) and The American Crisis (1776–1783), two of the most influential pamphlets at the start of the American Revolution, and he helped to inspire the Patriots in 1776 to declare independence from Great Britain. His ideas reflected Enlightenment-era ideals of human rights.

Joel Barlow was an American poet, diplomat, and politician. In politics, he supported the French Revolution and was an ardent Jeffersonian republican.

The Society of the Friends of the Constitution, renamed the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality after 1792 and commonly known as the Jacobin Club or simply the Jacobins, was the most influential political club during the French Revolution of 1789. The period of its political ascendancy includes the Reign of Terror, during which well over 10,000 people were put on trial and executed in France, many for political crimes.

The Girondins, or Girondists, were a political group during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnards, they initially were part of the Jacobin movement. They campaigned for the end of the monarchy, but then resisted the spiraling momentum of the Revolution, which caused a conflict with the more radical Montagnards. They dominated the movement until their fall in the insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793, which resulted in the domination of the Montagnards and the purge and eventual mass execution of the Girondins. This event is considered to mark the beginning of the Reign of Terror.

The National Convention was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the one-year Legislative Assembly. Created after the great insurrection of 10 August 1792, it was the first French government organized as a republic, abandoning the monarchy altogether. The Convention sat as a single-chamber assembly from 20 September 1792 to 26 October 1795.

The sans-culottes were the common people of the lower classes in late 18th-century France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their poor quality of life under the Ancien Régime. The word sans-culotte, which is opposed to "aristocrat", seems to have been used for the first time on 28 February 1791 by Jean-Bernard Gauthier de Murnan in a derogatory sense, speaking about a "sans-culottes army". The word came into vogue during the demonstration of 20 June 1792.

Jacques René Hébert was a French journalist and the founder and editor of the extreme radical newspaper Le Père Duchesne during the French Revolution.

The Law of Suspects was a decree passed by the French National Convention on 17 September 1793, during the French Revolution. Some historians consider this decree the start of the Reign of Terror; they argue that the decree marked a significant weakening of individual freedoms that led to "revolutionary paranoia" that swept the nation.

Jean-Baptiste du Val-de-Grâce, baron de Cloots, better known as Anacharsis Cloots, was a Prussian nobleman who was a significant figure in the French Revolution. Perhaps the first to advocate a world parliament, long before Albert Camus and Albert Einstein, he was a world federalist and an internationalist anarchist. He was nicknamed "orator of mankind", "citizen of humanity" and "a personal enemy of God".

The Cult of Reason was France's first established state-sponsored atheistic religion, intended as a replacement for Roman Catholicism during the French Revolution. After holding sway for barely a year, in 1794 it was officially replaced by the rival deistic Cult of the Supreme Being, promoted by Robespierre. Both cults were officially banned in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte with his Law on Cults of 18 Germinal, Year X.

The Hébertists, or Exaggerators were a radical revolutionary political group associated with the populist journalist Jacques Hébert, a member of the Cordeliers club. They came to power during the Reign of Terror and played a significant role in the French Revolution.

Zalkind Hourwitz (1751–1812) was a Polish Jew from Lublin living in Metz then Paris, active in the political discussions of the French Revolution. His essay, Vindication of the Jews, was one of three winning essays answering the Royal Society of Arts and Sciences in the city of Metz's question : "Are there means for making the Jews happier and more useful in France?"

The Revolution Controversy was a British debate over the French Revolution from 1789 to 1795. A pamphlet war began in earnest after the publication of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), which defended the House of Bourbon, the French aristocracy, and the Catholic Church in France. Because he had supported the American Patriots in their rebellion against Great Britain, Burke's views sent a shockwave through the British Isles. Many writers responded to defend the French Revolution, such as Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. Alfred Cobban calls the debate that erupted "perhaps the last real discussion of the fundamentals of politics" in Britain. The themes articulated by those responding to Burke would become a central feature of the radical working-class movement in Britain in the 19th century and of Romanticism. Most Britons celebrated the storming of the Bastille in 1789 and believed that Kingdom of France should be curtailed by a more democratic form of government. However, by December 1795, after the Reign of Terror and the War of the First Coalition, few still supported the French cause.

John Hurford Stone (1763–1818) was a British radical political reformer and publisher who spent much of his life in France.

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the most widely known, influential, and controversial figures of the French Revolution.

The revolutionary sections of Paris were subdivisions of Paris during the French Revolution. They first arose in 1790 and were suppressed in 1795.

Historians since the late 20th century have debated how women shared in the French Revolution and what impact it had on French women. Women had no political rights in pre-Revolutionary France; they were considered "passive" citizens, forced to rely on men to determine what was best for them. That changed dramatically in theory as there seemingly were great advances in feminism. Feminism emerged in Paris as part of a broad demand for social and political reform. These women demanded equality to men and then moved on to a demand for the end of male domination. Their chief vehicle for agitation were pamphlets and women's clubs, especially the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women. However, the Jacobin element in power abolished all the women's clubs in October 1793 and arrested their leaders. The movement was crushed. Devance explains the decision in terms of the emphasis on masculinity in wartime, Marie Antoinette's bad reputation for feminine interference in state affairs, and traditional male supremacy. A decade later the Napoleonic Code confirmed and perpetuated women's second-class status.

Thomas Walker (1749–1817) was an English cotton merchant and political radical.