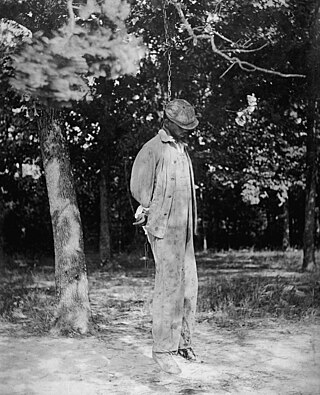

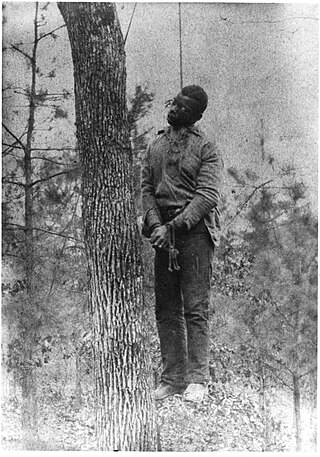

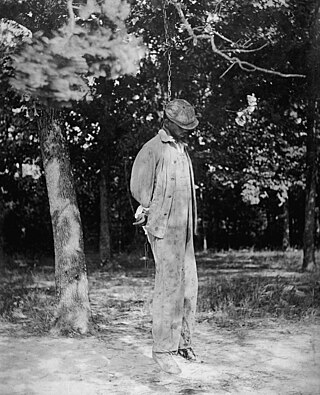

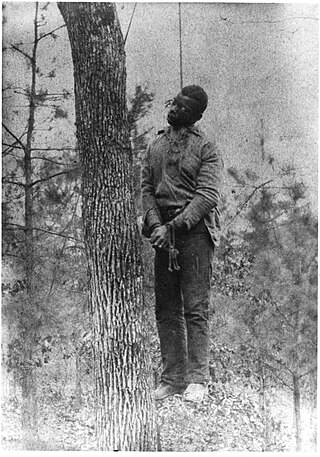

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an extreme form of informal group social control, and it is often conducted with the display of a public spectacle for maximum intimidation. Instances of lynchings and similar mob violence can be found in every society.

Cairo is the southernmost city in Illinois and the county seat of Alexander County. A river city, Cairo has the lowest elevation of any location in Illinois and is the only Illinois city to be surrounded by levees. It is in the river-crossed area of Southern Illinois known as "Little Egypt", for which the city is named, after Egypt's capital on the Nile.

Brooklyn, is a village in St. Clair County, Illinois, United States. Located two miles north of East St. Louis, Illinois and three miles northeast of downtown St. Louis, Missouri, it is the oldest town incorporated by African Americans in the United States. Its motto is "Founded by Chance, Sustained by Courage." The mayor is Mayor Vera Banks-Glasper.

Black Belt Jones is a 1974 American blaxploitation martial arts film directed by Robert Clouse and starring Jim Kelly and Gloria Hendry. The film is a spiritual successor to Clouse's prior film Enter the Dragon, in which Kelly had a supporting role. Here, Kelly features in his first starring role as the eponymous character; is a local hero who fights the Mafia and a local drug dealer threatening his friend's dojo.

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s and ended during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the victims of lynchings were members of various ethnicities, after roughly 4 million enslaved African Americans were emancipated, they became the primary targets of white Southerners. Lynchings in the U.S. reached their height from the 1890s to the 1920s, and they primarily victimised ethnic minorities. Most of the lynchings occurred in the American South, as the majority of African Americans lived there, but racially motivated lynchings also occurred in the Midwest and border states.

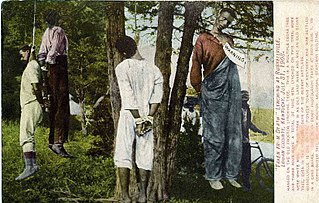

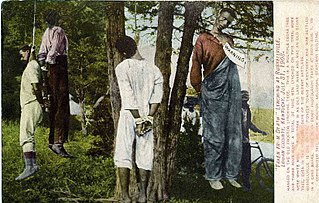

J. Thomas Shipp and Abraham S. Smith were African-American men who were murdered in a spectacle lynching by a group of thousands on August 7, 1930, in Marion, Indiana. They were taken from jail cells, beaten, and hanged from a tree in the county courthouse square. They had been arrested that night as suspects in a robbery, murder and rape case. A third African-American suspect, 16-year-old James Cameron, had also been arrested and narrowly escaped being killed by the mob; an unknown woman and a local sports hero intervened, and he was returned to jail. Cameron later stated that Shipp and Smith had committed the murder but that he had run away before that event.

The American Bottom is the flood plain of the Mississippi River in the Metro-East region of Southern Illinois, extending from Alton, Illinois, south to the Kaskaskia River. It is also sometimes called "American Bottoms". The area is about 175 square miles (450 km2), mostly protected from flooding in the 21st century by a levee and drainage canal system. Immediately across the river from St. Louis, Missouri, are industrial and urban areas, but nearby marshland, swamps, and the Horseshoe Lake are reminders of the Bottoms' riparian nature.

Winfield Taylor Durbin was an American politician serving as the 25th governor of the U.S. state of Indiana from 1901 to 1905. His term focused on progressive legislation and suppression of white cap vigilante organizations operating in the southern part of the state. He was the seventh and last veteran of the American Civil War to serve as governor.

White caps were groups involved in whitecapping who were operating in southern Indiana in the late 19th century. They engaged in vigilante justice and lynchings. In modern times, they are often viewed as engaging in terrorism. They became common in the state following the American Civil War and lasted until the turn of the 20th century. White caps were especially active in Crawford and neighboring counties in the late 1880s. Several members of the Reno Gang were lynched in 1868, causing an international incident. Some of the members had been extradited to the United States from Canada and were supposed to be under federal protection. Lynchings continued against other criminals, but when two possibly innocent men were killed in Corydon in 1889, Indiana responded by cracking down on the white cap vigilante groups, beginning in the administration of Isaac P. Gray.

Mondak is a ghost town in Roosevelt County, Montana, United States, which flourished c. 1903–1919, in large measure by selling alcohol to residents of North Dakota, then a dry state.

The Battle of Virden, also known as the Virden Mine Riot and Virden Massacre, was a labor union conflict and a racial conflict in central Illinois that occurred on October 12, 1898. After a United Mine Workers of America local struck a mine in Virden, Illinois, the Chicago-Virden Coal Company hired armed detectives or security guards to accompany African-American strikebreakers to start production again. An armed conflict broke out when the train carrying these men arrived at Virden. Strikers were also armed: a total of five detective/security guards and eight striking mine workers were killed, with five guards and more than thirty miners wounded. In addition, at least one black strikebreaker on the train was wounded. The engineer was shot in the arm. This was one of several fatal conflicts in the area at the turn of the century that reflected both labor union tension and racial violence. Virden, at this point, became a sundown town, and most black miners were expelled from Macoupin County.

John Temple Graves was an American newspaper editor who is best known for being the vice presidential nominee of the Independence Party in the presidential election of 1908.

In the early hours of 3 June 1893, a black day-laborer named Samuel J. Bush was forcibly taken from the Macon County, Illinois, jail and lynched. Mr. Bush stood accused of raping Minnie Cameron Vest, a white woman, who lived in the nearby town of Mount Zion.

William "Froggie" James, an African-American man, was lynched and his dead body mutilated on November 11, 1909 by a mob in Cairo, Illinois after he was charged with the rape and murder of 23-year-old shop clerk Anna Pelley.

Samuel "Mingo Jack" Johnson was an African American man falsely accused of rape. He was brutally beaten and hanged by a mob of white men in Eatontown, New Jersey.

A lynching postcard is a postcard bearing the photograph of a lynching—a vigilante murder usually motivated by racial hatred—intended to be distributed, collected, or kept as a souvenir. Often a lynching postcard would be inscribed with racist text or poems. Lynching postcards were in widespread production for more than fifty years in the United States; although their distribution through the United States Postal Service was banned in 1908.

The lynching of George White occurred on Monday, June 22, 1903, in Wilmington, Delaware. White was a black farmer who was accused of the rape and murder of Helen Bishop, who was arrested and brought to the workhouse. On the evening of June 22, under the impression that the local authorities were not reacting severely or soon enough, a large mob of white men marched to the workhouse, broke their way in, and forced White out of his cell. He was then brought to the site of Helen Bishop's death, tied to a stake, and burned. This is often referred to as the only lynching in Delaware.

The Carterville Mine Riot was part of the turn-of-the-century Illinois coal wars in the United States. The national United Mine Workers of America coal strike of 1897 was officially settled for Illinois District 12 in January 1898, with the vast majority of operators accepting the union terms: thirty-six to forty cents per ton, an 8-hour day, and union recognition. However, several mine owners in Carterville, Virden, and Pana, refused or abrogated. They attempted to run with African-American strikebreakers from Alabama and Tennessee. At the same time, lynching and racial exclusion were increasingly practiced by local white mining communities. Racial segregation was enforced within and among UMWA-organized coal mines.

The Danville race riot occurred on July 25, 1903, in Danville, Illinois, when a mob sought to lynch a black man who had been arrested. On their way to county jail, an altercation occurred that led to the death of a rioter and the subsequent lynching of another black man. At least two other black residents were also assaulted. The rioters failed to overtake the police stationed at the jail and the Illinois National Guard restored order the next day.

The lynching of William Johnson occurred at Thebes, Illinois on April 26, 1903. Johnson had been accused of assaulting a 10-year-old girl. He was apprehended by a mob of farmers and hanged.