Macon County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2020 United States Census, it had a population of 103,998. Its county seat is Decatur.

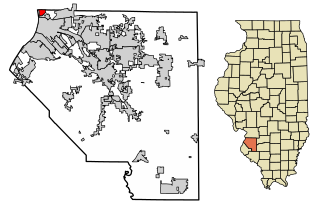

Brooklyn, is a village in St. Clair County, Illinois, United States. Located two miles north of East St. Louis, Illinois and three miles northeast of downtown St. Louis, Missouri, it is the oldest town incorporated by African Americans in the United States. Its motto is "Founded by Chance, Sustained by Courage." The mayor is Mayor Vera Banks-Glasper.

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett was an American investigative journalist, educator, and early leader in the civil rights movement. She was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Wells dedicated her career to combating prejudice and violence, and advocating for African-American equality—especially that of women.

Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States, and in one rural county in Arkansas. The term "Red Summer" was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who had been employed as a field secretary by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 1916. In 1919, he organized peaceful protests against the racial violence.

Charles Samuel Deneen was an American lawyer and Republican politician who served as the 23rd Governor of Illinois, from 1905 to 1913. He was the first Illinois governor to serve two consecutive terms totalling eight years. He was governor during the infamous Springfield race riot of 1908, which he helped put down. He later served as a U.S. Senator from Illinois, from 1925 to 1931. Deneen had previously served as a member of the Illinois House of Representatives from 1892 to 1894. As an attorney, he had been the lead prosecutor in Chicago's infamous Adolph Luetgert murder trial.

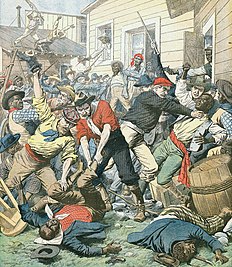

The Springfield race riot of 1908 consisted of events of mass racial violence committed against African Americans by a mob of about 5,000 white Americans and European immigrants in Springfield, Illinois, between August 14 and 16, 1908. Two black men had been arrested as suspects in a rape, and attempted rape and murder. The alleged victims were two young white women and the father of one of them. When a mob seeking to lynch the men discovered the sheriff had transferred them out of the city, the whites furiously spread out to attack black neighborhoods, murdered black citizens on the streets, and destroyed black businesses and homes. The state militia was called out to quell the rioting.

Henry Smith was an African-American youth who was lynched in Paris, Texas. Smith allegedly confessed to murdering the three-year-old daughter of a law enforcement officer who had allegedly beaten him during an arrest. Smith fled, but was recaptured after a nationwide manhunt. He was then returned to Paris, where he was turned over to a mob and burned at the stake. His lynching was covered by The New York Times and attracted national publicity.

Anthony Crawford was an African American man who was killed by a lynch mob in Abbeville, South Carolina on October 21, 1916.

Ell Persons was a black man who was lynched on 22 May 1917, after he was accused of having raped and decapitated a 15-year-old white girl, Antoinette Rappel, in Memphis, Tennessee, United States. He was arrested and was awaiting trial when he was captured by a lynch party, who burned him alive and scattered his remains around town, throwing his head at a group of African Americans. A large crowd attended his lynching, which had the atmosphere of a carnival. No one was charged as a result of the lynching, which was described as one of the most vicious in American history, but it did play a part in the foundation of the Memphis chapter of the NAACP.

In Forsyth County, Georgia, in September 1912, two separate alleged attacks on white women in the Cumming area resulted in black men being accused as suspects. First, a white woman reportedly awoke to find a black man in her bedroom; then days later, a teenage white woman was beaten and raped, later dying of her injuries.

Ferdinand Lee Barnett was an American journalist, lawyer, and civil rights activist in Chicago, beginning in the late Reconstruction era.

R. C. O. Benjamin was a journalist, lawyer, and minister in the United States. He was an editor or contributor to numerous newspapers throughout the country, and may have been the first black editor of a white paper when he became editor of the Daily Sun In Los Angeles. He was also possibly the first black man admitted to the California bar, and may have been admitted to the bar in twelve states. In 1900 he was working as a prominent lawyer in Lexington Kentucky when he was beaten for helping register black voters by a white man who opposed his efforts. Later that day he was killed by the same man.

William "Froggie" James, an African-American man, was lynched and his dead body mutilated on November 11, 1909 by a mob in Cairo, Illinois, after he was charged with the rape and murder of 23-year-old shop clerk Anna Pelley.

David Wyatt was an African-American teacher in Brooklyn, Illinois. In June 1903, Wyatt was denied renewal for his teaching certificate by the district superintendent, Charles Hertel. After hearing about his denial, Wyatt shot Hertel and was immediately arrested. While in jail, a mob captured Wyatt, lynched him in the public square, and set his body on fire.

Ephraim Grizzard and Henry Grizzard were African-American brothers who were lynched in Middle Tennessee in April 1892 as suspects in the assaults on two white sisters. Henry Grizzard was hanged by a white mob on April 24 near the house of the young women in Goodlettsville, Tennessee.

Paul Jones was lynched on November 2, 1919, after being accused of attacking a fifty-year-old white woman in Macon, Georgia.

The Carterville Mine Riot was part of the turn-of-the-century Illinois coal wars in the United States. The national United Mine Workers of America coal strike of 1897 was officially settled for Illinois District 12 in January 1898, with the vast majority of operators accepting the union terms: thirty-six to forty cents per ton, an 8-hour day, and union recognition. However, several mine owners in Carterville, Virden, and Pana, refused or abrogated. They attempted to run with African-American strikebreakers from Alabama and Tennessee. At the same time, lynching and racial exclusion were increasingly practiced by local white mining communities. Racial segregation was enforced within and among UMWA-organized coal mines.

Styles Linton Hutchins was an attorney, politician, and activist in South Carolina, Georgia, and Tennessee between 1877 and 1906. Hutchins was among the last African Americans to graduate from the University of South Carolina School of Law in the brief window during Reconstruction when the school was open to Black students and the first Black attorney admitted to practice in Georgia. He practiced law and participated in local politics in Georgia and Tennessee, served a single term (1887-1888) in the Tennessee General Assembly as one of its last Black members before an era of entrenched white supremacy that lasted until 1965, and advocated for the interests of African Americans. He called for reparations and attempted to identify or create a separate homeland for Blacks. He was a member of the defense team in the 1906 appeal on civil rights grounds by Ed Johnson of a conviction of rape, a case which reached the Supreme Court before it was halted by Johnson's murder by lynching in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Joe Smith was an African-American man who was lynched by a mob in Yazoo City, Mississippi, on July 7, 1927.