Related Research Articles

In the broader context of racism in the United States, mass racial violence in the United States consists of ethnic conflicts and race riots, along with such events as:

The 1967 Detroit riot, also known as the 12th Street Riot, was the bloodiest of the urban riots in the United States during the "Long, hot summer of 1967". Composed mainly of confrontations between black residents and the Detroit Police Department, it began in the early morning hours of Sunday July 23, 1967, in Detroit, Michigan.

Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States, and in one rural county in Arkansas. The term "Red Summer" was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who had been employed as a field secretary by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 1916. In 1919, he organized peaceful protests against the racial violence.

The East St. Louis massacre was a series of violent attacks on African Americans by white Americans in East St. Louis, Illinois between late May and early July of 1917. These attacks also displaced 6,000 African Americans and led to the destruction of approximately $400,000 worth of property. They occurred in East St. Louis, an industrial city on the east bank of the Mississippi River, directly opposite the city of St. Louis, Missouri. The July 1917 episode in particular was marked by white-led violence throughout the city. The multi-day rioting has been described as the "worst case of labor-related violence in 20th-century American history", and among the worst racial riots in U.S. history.

The 1991 Washington, D.C., riot, sometimes referred to as the Mount Pleasant riot or Mount Pleasant Disturbance, occurred in May 1991, when rioting broke out in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Washington, D.C., in response to an African-American female police officer having shot a Salvadoran man in the chest following a Cinco de Mayo celebration.

The Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company (ADDSCO) located in Mobile, Alabama, was one of the largest marine production facilities in the United States during the 20th century. It began operation in 1917, and expanded dramatically during World War II; with 30,000 workers, including numerous African Americans and women, it became the largest employer in the southern part of the state. During the defense buildup, which included other shipyards, Mobile became the second-largest city in the state, after Birmingham.

The 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre, also known as the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, was an episode of mass racial violence against African Americans in the United States in September 1906. Violent attacks by armed mobs of White Americans against African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, began after newspapers, on the evening of September 22, 1906, published several unsubstantiated and luridly detailed reports of the alleged rapes of 4 local women by black men. The violence lasted through September 24, 1906. The events were reported by newspapers around the world, including the French Le Petit Journal which described the "lynchings in the USA" and the "massacre of Negroes in Atlanta," the Scottish Aberdeen Press & Journal under the headline "Race Riots in Georgia," and the London Evening Standard under the headlines "Anti-Negro Riots" and "Outrages in Georgia." The final death toll of the conflict is unknown and disputed, but officially at least 25 African Americans and two whites died. Unofficial reports ranged from 10–100 black Americans killed during the massacre. According to the Atlanta History Center, some black Americans were hanged from lampposts; others were shot, beaten or stabbed to death. They were pulled from street cars and attacked on the street; white mobs invaded black neighborhoods, destroying homes and businesses.

The 1943Detroit race riot took place in Detroit, Michigan, from the evening of June 20 through to the early morning of June 22. It occurred in a period of dramatic population increase and social tensions associated with the military buildup of U.S. participation in World War II, as Detroit's automotive industry was converted to the war effort. Existing social tensions and housing shortages were exacerbated by racist feelings about the arrival of nearly 400,000 migrants, both African-American and White Southerners, from the Southeastern United States between 1941 and 1943. The migrants competed for space and jobs against the city's residents as well as against European immigrants and their descendants. The riot escalated after a false rumor spread that a mob of whites had thrown a black mother and her baby into the Detroit River. Blacks looted and destroyed white property as retaliation. Whites overran Woodward to Veron where they proceeded to violently attack black community members and tip over 20 cars that belonged to black families.

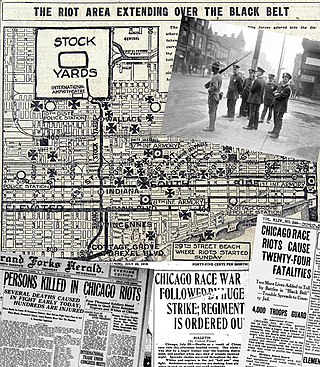

The Chicago race riot of 1919 was a violent racial conflict between white Americans and black Americans that began on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, on July 27 and ended on August 3, 1919. During the riot, 38 people died. Over the week, injuries attributed to the episodic confrontations stood at 537, two-thirds black and one-third white; and between 1,000 and 2,000 residents, most of them black, lost their homes. Due to its sustained violence and widespread economic impact, it is considered the worst of the scores of riots and civil disturbances across the United States during the "Red Summer" of 1919, so named because of its racial and labor violence. It was also one of the worst riots in the history of Illinois.

A race riot took place in Harlem, New York City, on August 1 and 2 of 1943, after a white police officer, James Collins, shot and wounded Robert Bandy, an African American soldier; and rumors circulated that the soldier had been killed. The riot was chiefly directed by Black residents against white-owned property in Harlem. It was one of five riots in the nation that year related to Black and white tensions during World War II. The others took place in Detroit; Beaumont, Texas; Mobile, Alabama; and Los Angeles.

From 1967 to 1973, an extended period of racial unrest occurred in the town of Cairo, Illinois. The city had long had racial tensions which boiled over after a black soldier was found hanged in his jail cell. Over the next several years, fire bombings, racially charged boycotts and shootouts were common place in Cairo, with 170 nights of gunfire reported in 1969 alone.

The Fernwood Park Race Riot was a race massacre instigated by white residents against African American residents who inhabited the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) veterans' housing project in the Fernwood Park neighborhood in Chicago. Area residents viewed this as one of several attempts by the CHA to initiate racial integration into white communities. The riot took place between 98th and 111th streets and lasted for three days, from the day veterans and their families moved into the project, August 13th, 1947 to August 16th, 1947. The Chicago Police Department did little to stop the rioting, as was the case a year before at the Airport Homes race riots. It was one of the worst race riots in Chicago history.

The Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) was created in 1941 in the United States to implement Executive Order 8802 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt "banning discriminatory employment practices by Federal agencies and all unions and companies engaged in war-related work." That was shortly before the United States entered World War II. The executive order also required federal vocational and training programs to be administered without discrimination. Established in the Office of Production Management, the FEPC was intended to help African Americans and other minorities obtain jobs in home front industries during World War II. In practice, especially in its later years, the committee also tried to open up more skilled jobs in industry to minorities, who had often been restricted to lowest-level work. The FEPC appeared to have contributed to substantial economic improvements among black men during the 1940s by helping them gain entry to more skilled and higher-paying positions in defense-related industries.

The Longview race riot was a series of violent incidents in Longview, Texas, between July 10 and July 12, 1919, when whites attacked black areas of town, killed one black man, and burned down several properties, including the houses of a black teacher and a doctor. It was one of the many race riots in 1919 in the United States during what became known as Red Summer, a period after World War I known for numerous riots occurring mostly in urban areas.

The 1967 Milwaukee riot was one of 159 race riots that swept cities in the United States during the "Long Hot Summer of 1967". In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, African American residents, outraged by the slow pace in ending housing discrimination and police brutality, began to riot on the evening of July 30, 1967. The inciting incident was a fight between teenagers, which escalated into full-fledged rioting with the arrival of police. Within minutes, arson, looting, and sniping were occurring in the north side of the city, primarily the 3rd Street Corridor.

The Washington race riot of 1919 was civil unrest in Washington, D.C. from July 19, 1919, to July 24, 1919. Starting July 19, white men, many in the armed forces, responded to the rumored arrest of a black man for the rape of a white woman with four days of mob violence against black individuals and businesses. They rioted, randomly beat black people on the street, and pulled others off streetcars for attacks. When police refused to intervene, the black population fought back. The city closed saloons and theaters to discourage assemblies. Meanwhile, the four white-owned local papers, including the Washington Post, fanned the violence with incendiary headlines and calling in at least one instance for mobilization of a "clean-up" operation.

The 1917 Chester race riot was a race riot in Chester, Pennsylvania that took place over four days in July 1917. Racial tensions increased greatly during the World War I industrial boom due to white hostility toward the large influx of southern blacks who moved North as part of the Great Migration. The riot began after a black man walking in a white neighborhood with his girlfriend and another couple bumped into each other. This led to a fight in which the black man stabbed and killed the white man. In retaliation, white gangs targeted and attacked blacks throughout the city. Four days of violent melees involving mobs of hundreds of people followed. The Chester police along with the Pennsylvania National Guard, Pennsylvania State Police, mounted police officers and a 150-person posse finally quelled the riot after four days. The riot resulted in 7 deaths, 28 gunshot wounds, 360 arrests and hundreds of hospitalizations.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 James A. Burran, "Violence in an 'Arsenal of Democracy': The Beaumont Race Riot, 1943", East Texas Historical Journal, 1976 Vol. 14, Issue 1, Article 8, available at ScholarWorks, accessed September 20, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 James S. Olson, "Beaumont Riot of 1943", Handbook of Texas Online, uploaded on June 10, 2010, accessed September 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Civil Rights' Case Is Closed". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal . January 17, 1943 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Lippold, Pam (2006). "Recollections: Revisiting the Beaumont Race Riot of 1943". Touchstone. 25: 52–65. Retrieved March 24, 2007.[ dead link ]

- ↑ "One Dead, 11 Hurt In Beaumont Riots". The Paris News . June 16, 1943 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ El Paso Herald-Post (El Paso, Texas) · 16 Jun 1943, Wed · Page 12 - via Newspapers.com

- ↑ "Beaumont Race Riot, 1943, Black Past website.

- ↑ "News". THE EXAMPLE: HISTORICAL FICTION FILM.