In the broader context of racism in the United States, mass racial violence in the United States consists of ethnic conflicts and race riots, along with such events as:

Rowan County is a county in the U.S. state of North Carolina that was formed in 1753, as part of the British Province of North Carolina. It was originally a vast territory with unlimited western boundaries, but its size was reduced to 524 square miles (1,360 km2) after several counties were formed from Rowan County in the 18th and 19th centuries. As of the 2020 census, its population was 146,875. Its county seat, Salisbury, is the oldest continuously populated European-American town in the western half of North Carolina. Rowan County is located northeast of Charlotte, and is considered part of the Charlotte-Concord-Gastonia, NC-SC Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Lake City is a city in Florence County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 6,675 at the 2010 census. Located in central South Carolina, it is south of Florence and included as part of the Florence Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Columbia is a city in and the county seat of Maury County, Tennessee. The population was 41,690 as of the 2020 United States census. Columbia is included in the Nashville metropolitan area.

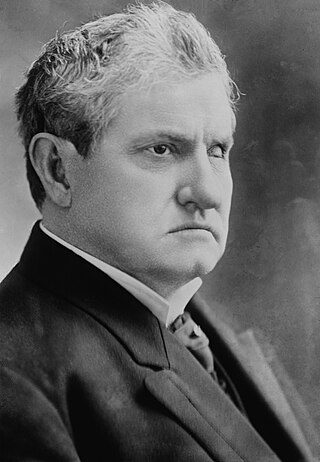

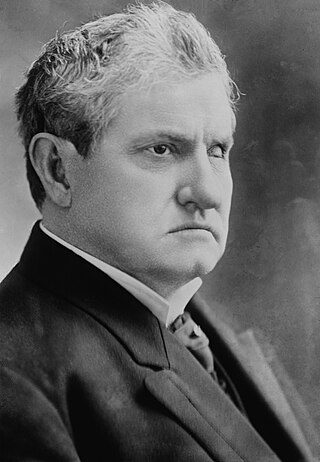

Benjamin Ryan Tillman was a politician of the Democratic Party who served as governor of South Carolina from 1890 to 1894, and as a United States Senator from 1895 until his death in 1918. A white supremacist who opposed civil rights for black Americans, Tillman led a paramilitary group of Red Shirts during South Carolina's violent 1876 election. On the floor of the U.S. Senate, he defended lynching, and frequently ridiculed black Americans in his speeches, boasting of having helped kill them during that campaign.

William Dorsey Jelks was an American newspaper editor, publisher, and politician who served as the 32nd Governor of Alabama from 1901 to 1907. As Lieutenant Governor of Alabama, he also served as acting governor between December 1 and December 26, 1900, when Governor William J. Samford was out-of-state seeking medical treatment.

Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States, and in one rural county in Arkansas. The term "Red Summer" was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who had been employed as a field secretary by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 1916. In 1919, he organized peaceful protests against the racial violence.

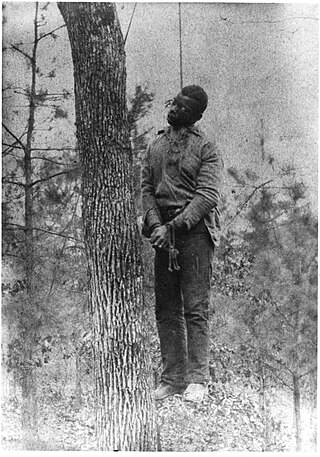

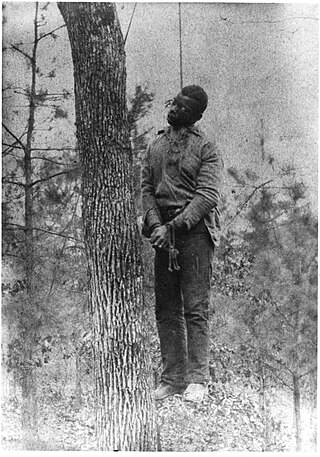

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s and ended during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the victims of lynchings were members of various ethnicities, after roughly 4 million enslaved African Americans were emancipated, they became the primary targets of white Southerners. Lynchings in the U.S. reached their height from the 1890s to the 1920s, and they primarily victimized ethnic minorities. Most of the lynchings occurred in the American South, as the majority of African Americans lived there, but racially motivated lynchings also occurred in the Midwest and border states. In 1891, the largest single mass lynching in American history was perpetrated in New Orleans against Italian immigrants.

The Springfield race riot of 1908 consisted of events of mass racial violence committed against African Americans by a mob of about 5,000 white Americans and European immigrants in Springfield, Illinois, between August 14 and 16, 1908. Two black men had been arrested as suspects in a rape, and attempted rape and murder. The alleged victims were two young white women and the father of one of them. When a mob seeking to lynch the men discovered the sheriff had transferred them out of the city, the whites furiously spread out to attack black neighborhoods, murdered black citizens on the streets, and destroyed black businesses and homes. The state militia was called out to quell the rioting.

The Wilmington insurrection of 1898, also known as the Wilmington massacre of 1898 or the Wilmington coup of 1898, was a coup d'état and a massacre which was carried out by white supremacists in Wilmington, North Carolina, United States, on Thursday, November 10, 1898. The white press in Wilmington originally described the event as a race riot caused by black people. Since the late 20th century and further study, the event has been characterized as a violent overthrow of a duly elected government by a group of white supremacists.

The Robert Charles riots of July 24–27, 1900 in New Orleans, Louisiana were sparked after Afro-American laborer Robert Charles fatally shot a white police officer during an altercation and escaped arrest. A large manhunt for him ensued, and a white mob started rioting, attacking blacks throughout the city. The manhunt for Charles began on Monday, July 23, 1900, and ended when Charles was killed on Friday, July 27, shot by a special police volunteer. The mob shot him hundreds more times, and beat the body.

The National Afro-American Council was the first nationwide civil rights organization in the United States, created in 1898 in Rochester, New York. Before its dissolution a decade later, the Council provided both the first national arena for discussion of critical issues for African Americans and a training ground for some of the nation's most famous civil rights leaders in the 1910s, 1920s, and beyond.

Anthony Crawford was an African American man who was killed by a lynch mob in Abbeville, South Carolina on October 21, 1916.

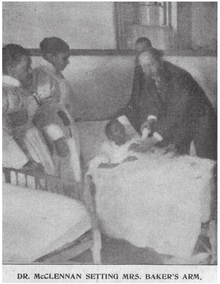

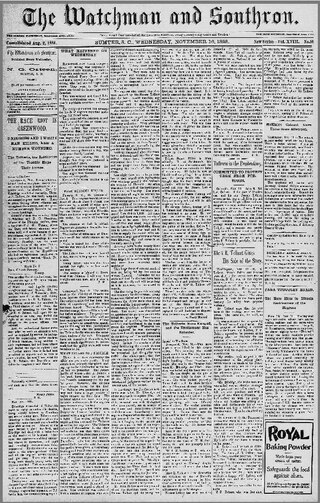

The Phoenix election riot occurred on November 8, 1898, near Greenwood County, South Carolina, when a group of local white Democrats attempted to stop a Republican election official from taking the affidavits of African Americans who had been denied the ability to vote. The race-based riot was part of numerous efforts by white conservative Democrats to suppress voting by blacks, as they had largely supported the Republican Party since the Reconstruction era. Beginning with Mississippi in 1890, and South Carolina in 1895, southern states were passing new constitutions and laws designed to disenfranchise blacks by making voter registration and voting more difficult.

The Longview race riot was a series of violent incidents in Longview, Texas, between July 10 and July 12, 1919, when whites attacked black areas of town, killed one black man, and burned down several properties, including the houses of a black teacher and a doctor. It was one of the many race riots in 1919 in the United States during what became known as Red Summer, a period after World War I known for numerous riots occurring mostly in urban areas.

The lynching of the Walker family took place near Hickman, Fulton County, Kentucky, on October 3, 1908, at the hands of about fifty masked Night Riders. David Walker was a landowner, with a 21.5-acre (8.7 ha) farm. The entire family of seven African Americans including parents, infant in arms, and four children were killed, with the event reported by national newspapers. Governor Augustus E. Willson of Kentucky strongly condemned the murders and promised a reward for information leading to prosecution. No one was ever prosecuted.

John Hartfield was a black man who was lynched in Ellisville, Mississippi in 1919 for allegedly having a white girlfriend. The murder was announced a day in advance in major newspapers, a crowd of as many as 10,000 watched while Hartfield was hanged, shot, and burned. Pieces of his corpse were chopped off and sold as souvenirs.

The lynching of Paul Reed and Will Cato occurred in Statesboro, Georgia on August 16, 1904. Five members of a white farm family, the Hodges, had been murdered and their house burned to hide the crime. Paul Reed and Will Cato, who were African-American, were tried and convicted for the murders. Despite militia having been brought in from Savannah to protect them, the two men were taken by a mob from the courthouse immediately after their trials, chained to a tree stump, and burned. In the immediate aftermath, four more African-Americans were shot, three of them dying, and others were flogged.

The Seminole burning was the lynching by live burning of two Seminole youth, Lincoln McGeisey and Palmer Sampson, near Maud, Oklahoma, on January 8, 1898.