A terrestrial planet, telluric planet, or rocky planet, is a planet that is composed primarily of silicate rocks or metals. Within the Solar System, the terrestrial planets accepted by the IAU are the inner planets closest to the Sun: Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. Among astronomers who use the geophysical definition of a planet, two or three planetary-mass satellites – Earth's Moon, Io, and sometimes Europa – may also be considered terrestrial planets; and so may be the rocky protoplanet-asteroids Pallas and Vesta. The terms "terrestrial planet" and "telluric planet" are derived from Latin words for Earth, as these planets are, in terms of structure, Earth-like. Terrestrial planets are generally studied by geologists, astronomers, and geophysicists.

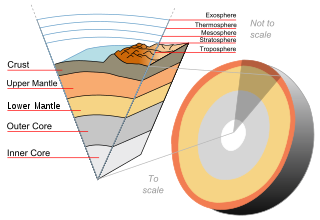

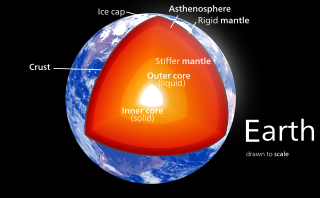

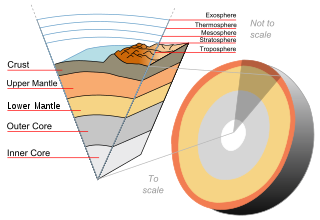

In geology, the crust is the outermost solid shell of a rocky planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite. It is usually distinguished from the underlying mantle by its chemical makeup; however, in the case of icy satellites, it may be distinguished based on its phase.

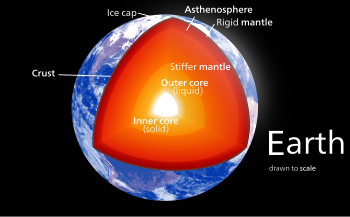

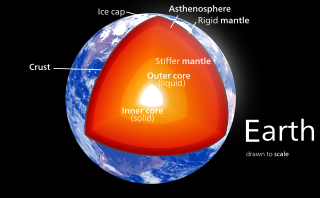

A lithosphere is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the lithospheric mantle, the topmost portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years or more. The crust and upper mantle are distinguished on the basis of chemistry and mineralogy.

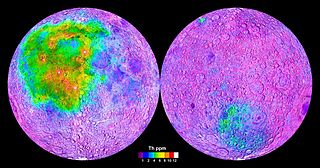

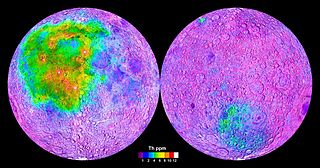

KREEP, an acronym built from the letters K, REE and P, is a geochemical component of some lunar impact breccia and basaltic rocks. Its most significant feature is somewhat enhanced concentration of a majority of so-called "incompatible" elements and the heat-producing elements, namely radioactive uranium, thorium, and potassium.

In planetary science, planetary differentiation is the process by which the chemical elements of a planetary body accumulate in different areas of that body, due to their physical or chemical behavior. The process of planetary differentiation is mediated by partial melting with heat from radioactive isotope decay and planetary accretion. Planetary differentiation has occurred on planets, dwarf planets, the asteroid 4 Vesta, and natural satellites.

Peridotite ( PERR-ih-doh-tyte, pə-RID-ə-) is a dense, coarse-grained igneous rock consisting mostly of the silicate minerals olivine and pyroxene. Peridotite is ultramafic, as the rock contains less than 45% silica. It is high in magnesium (Mg2+), reflecting the high proportions of magnesium-rich olivine, with appreciable iron. Peridotite is derived from Earth's mantle, either as solid blocks and fragments, or as crystals accumulated from magmas that formed in the mantle. The compositions of peridotites from these layered igneous complexes vary widely, reflecting the relative proportions of pyroxenes, chromite, plagioclase, and amphibole.

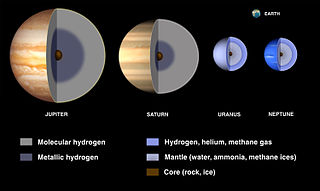

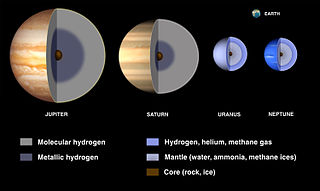

A planetary core consists of the innermost layers of a planet. Cores may be entirely solid or entirely liquid, or a mixture of solid and liquid layers as is the case in the Earth. In the Solar System, core sizes range from about 20% to 85% of a planet's radius (Mercury).

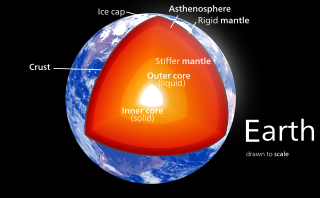

Earth's mantle is a layer of silicate rock between the crust and the outer core. It has a mass of 4.01×1024 kg (8.84×1024 lb) and thus makes up 67% of the mass of Earth. It has a thickness of 2,900 kilometers (1,800 mi) making up about 46% of Earth's radius and 84% of Earth's volume. It is predominantly solid but, on geologic time scales, it behaves as a viscous fluid, sometimes described as having the consistency of caramel. Partial melting of the mantle at mid-ocean ridges produces oceanic crust, and partial melting of the mantle at subduction zones produces continental crust.

The internal structure of Earth is the layers of the Earth, excluding its atmosphere and hydrosphere. The structure consists of an outer silicate solid crust, a highly viscous asthenosphere and solid mantle, a liquid outer core whose flow generates the Earth's magnetic field, and a solid inner core.

Ceres, minor-planet designation 1 Ceres, is a dwarf planet in the middle main asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. It was the first asteroid discovered on 1 January 1801, by Giuseppe Piazzi at Palermo Astronomical Observatory in Sicily and announced as a new planet. Ceres was later classified as an asteroid and then a dwarf planet, the only one always inside Neptune's orbit.

Having a mean density of 3,346.4 kg/m3, the Moon is a differentiated body, being composed of a geochemically distinct crust, mantle, and planetary core. This structure is believed to have resulted from the fractional crystallization of a magma ocean shortly after its formation about 4.5 billion years ago. The energy required to melt the outer portion of the Moon is commonly attributed to a giant impact event that is postulated to have formed the Earth-Moon system, and the subsequent reaccretion of material in Earth orbit. Crystallization of this magma ocean would have given rise to a mafic mantle and a plagioclase-rich crust.

The geology of solar terrestrial planets mainly deals with the geological aspects of the four terrestrial planets of the Solar System – Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars – and one terrestrial dwarf planet: Ceres. Earth is the only terrestrial planet known to have an active hydrosphere.

The presence of water on the terrestrial planets of the Solar System varies with each planetary body, with the exact origins remaining unclear. Additionally, the terrestrial dwarf planet Ceres is known to have water ice on its surface.

A planetary surface is where the solid or liquid material of certain types of astronomical objects contacts the atmosphere or outer space. Planetary surfaces are found on solid objects of planetary mass, including terrestrial planets, dwarf planets, natural satellites, planetesimals and many other small Solar System bodies (SSSBs). The study of planetary surfaces is a field of planetary geology known as surface geology, but also a focus on a number of fields including planetary cartography, topography, geomorphology, atmospheric sciences, and astronomy. Land is the term given to non-liquid planetary surfaces. The term landing is used to describe the collision of an object with a planetary surface and is usually at a velocity in which the object can remain intact and remain attached.

This is a glossary of terms used in meteoritics, the science of meteorites.

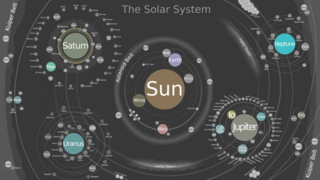

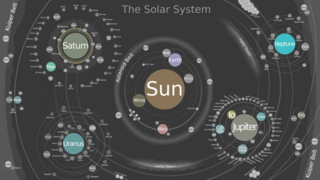

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the Solar System:

Planetary oceanography also called astro-oceanography or exo-oceanography is the study of oceans on planets and moons other than Earth. Unlike other planetary sciences like astrobiology, astrochemistry and planetary geology, it only began after the discovery of underground oceans in Saturn's moon Titan and Jupiter's moon Europa. This field remains speculative until further missions reach the oceans beneath the rock or ice layer of the moons. There are many theories about oceans or even ocean worlds of celestial bodies in the Solar System, from oceans made of diamond in Neptune to a gigantic ocean of liquid hydrogen that may exist underneath Jupiter's surface.

Comparative planetary science or comparative planetology is a branch of space science and planetary science in which different natural processes and systems are studied by their effects and phenomena on and between multiple bodies. The planetary processes in question include geology, hydrology, atmospheric physics, and interactions such as impact cratering, space weathering, and magnetospheric physics in the solar wind, and possibly biology, via astrobiology.

The geology of Ceres consists of the characteristics of the surface, the crust and the interior of the dwarf planet Ceres. The surface of Ceres is comparable to the surfaces of Saturn's moons Rhea and Tethys, and Uranus's moons Umbriel and Oberon.

The geochemistry of carbon is the study of the transformations involving the element carbon within the systems of the Earth. To a large extent this study is organic geochemistry, but it also includes the very important carbon dioxide. Carbon is transformed by life, and moves between the major phases of the Earth, including the water bodies, atmosphere, and the rocky parts. Carbon is important in the formation of organic mineral deposits, such as coal, petroleum or natural gas. Most carbon is cycled through the atmosphere into living organisms and then respirated back into the atmosphere. However an important part of the carbon cycle involves the trapping of living matter into sediments. The carbon then becomes part of a sedimentary rock when lithification happens. Human technology or natural processes such as weathering, or underground life or water can return the carbon from sedimentary rocks to the atmosphere. From that point it can be transformed in the rock cycle into metamorphic rocks, or melted into igneous rocks. Carbon can return to the surface of the Earth by volcanoes or via uplift in tectonic processes. Carbon is returned to the atmosphere via volcanic gases. Carbon undergoes transformation in the mantle under pressure to diamond and other minerals, and also exists in the Earth's outer core in solution with iron, and may also be present in the inner core.