Cripple Creek is a statutory city that is the county seat of Teller County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 1,155 at the 2020 United States Census. Cripple Creek is a former gold mining camp located 20 miles (32 km) southwest of Colorado Springs near the base of Pikes Peak. The Cripple Creek Historic District, which received National Historic Landmark status in 1961, includes part or all of the city and the surrounding area. The city is now a part of the Colorado Springs, CO Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Front Range Urban Corridor.

The Gold Belt Tour Scenic and Historic Byway is a National Scenic Byway, a Back Country Byway, and a Colorado Scenic and Historic Byway located in Fremont and Teller counties, Colorado, USA. The byway is named for the Gold Belt mining region. The Cripple Creek Historic District is a National Historic Landmark. The byway forms a three-legged loop with the Phantom Canyon Road, the Shelf Road, and the High Park Road (paved).

The Colorado Springs and Cripple Creek District Railway was a 4 ft 8+1⁄2 instandard gauge railroad operating in the U.S. state of Colorado around the turn of the 20th century.

The Midland Terminal Railway was a short line terminal railroad running from the Colorado Midland Railway near Divide to Cripple Creek, Colorado. The railroad made its last run in February 1949.

Old Colorado City, formerly Colorado City, was once a town, but it is now a neighborhood within the city of Colorado Springs, Colorado. Its commercial district was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. It was founded during the Pikes Peak Gold Rush of 1859 and was involved in the mining industry, both as a supply hub and as a gold ore processing center beginning in the 1890s. Residents of Colorado City worked at some of the 50 coal mines of the Colorado Springs area. It was briefly the capital of the Colorado Territory. For many years, Colorado Springs prohibited the use of alcohol within its border due to the lifestyle of Colorado City's opium dens, bordellos, and saloons. It is now a tourist area, with boutiques, art galleries, and restaurants.

Before it was founded, the site of modern-day Colorado Springs, Colorado, was part of the American frontier. Old Colorado City, built in 1859 during the Pike's Peak Gold Rush was the Colorado Territory capital. The town of Colorado Springs was founded by General William Jackson Palmer as a resort town. Old Colorado City was annexed into Colorado Springs. Railroads brought tourists and visitors to the area from other parts of the United States and abroad. The city was noted for junctions for seven railways: Denver and Rio Grande (1870), Denver and New Orleans Manitou Branch (1882), Colorado Midland (1886-1918), Colorado Springs and Interurban, Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe (1889), Rock Island (1889), and Colorado Springs and Cripple Creek Railways. It was also known for mining exchanges and brokers for the Cripple Creek Gold Rush.

Gold mining in Colorado, a state of the United States, has been an industry since 1858. It also played a key role in the establishment of the state of Colorado.

Austin Bluffs is a summit in the Pikeview area of Colorado Springs in El Paso County, Colorado, at 6,673 feet (2,034 m) in elevation. It is also a residential area, that was once a settlement and the site of a tuberculosis sanatorium. The University of Colorado Colorado Springs campus was moved there in 1965. The summit also lends its name to a principal arterial road of the Colorado Springs area which traverses the southern and central sections of the corridor. It divides the Austin Bluffs open space from Palmer Park, and the Templeton Gap is located here as well.

The Mollie Kathleen Gold Mine is a historic vertical shaft mine near Cripple Creek, Colorado. The mine shaft descends 1,000 feet (300 m) into the mountain, a depth roughly equal to the height of the Empire State Building in New York City. The mine currently gives tours, and is visited by around 40,000 people annually. The addition of the mines and subsequent tours of this mine and others in the area had considerable effect on the economies of both Victor, Colorado and Cripple Creek.

The Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mine, formerly and historically the Cresson Mine, is an active gold mine located near the town of Victor, in the Cripple Creek mining district in the US state of Colorado. The richest gold mine in Colorado history, it is the only remaining significant producer of gold in the state, and produced 322,000 troy ounces of gold in 2019, and reported 3.45 million troy ounces of Proven and Probable Reserves as at December 31, 2019. It was owned and operated by AngloGold Ashanti through its subsidiary, the Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mining Company (CC&V), until 2015, when it sold the mine to Newmont Mining Corporation.

Palmer Park is a regional park in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Located at 3650 Maizeland Road, the park is several miles northeast of the downtown area. Elevation Outdoors Magazine named it Best Urban Park in its Best of Rockies 2017 list. One of Best of the Springs Expert Picks - Sports & Recreation by The Gazette, Seth Boster states that it may have the city's best views of Pikes Peak and a place "where an escape into deep nature is easy. It is strange and marvelous to look out at urban sprawl while perched on some high rock ledge, surrounded by rugged wilderness."

Papeton, was a coal mining town, now in the area of Venetian Village, a neighborhood in Colorado Springs, Colorado, that is 1.4 miles (2.3 km) west southwest of Palmer Park. It is located at 6,184 feet (1,885 m) in elevation.

There are a wide range of recreational areas and facilities in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Pikeview is a neighborhood of Colorado Springs, annexed to the city as the "Pike View Addition" on August 1, 1962. In 1896 there was a Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad station in Pikeview, and miners had begun digging a shaft for the Pikeview Coal Mine. Pikeview also had a quarry beginning 1905 for the mining of limestone for concrete. Coal mining ended in 1957, but the Pikeview Quarry continues to operate. Quarry operations, though, have created a gash or scar in the landscape and efforts have been made since the late 1980s to reclaim the hillside landscape. The Greg Francis Bighorn Sheep Habitat in what had been Queens Canyon Quarry was founded in 2003 in recognition of the individuals and organizations that have worked to create a nature hillside habitat.

Colorado mining history is a chronology of precious metal mining, fuel extraction, building material quarrying, and rare earth mining.

The Cripple Creek Gold Rush was a period of gold production in the Cripple Creek area from the late 1800s until the early 1900s. Mining exchanges were in Cripple Creek, Colorado Springs, Pueblo and Victor. Smelting was in Gillett, Florence, and (Old) Colorado City. Mining communities sprang up quickly, but most lasted only as long as gold continued to be produced. Settlements included:

St. Peter's Dome is a granite-topped peak on Pikes Peak massif in the Pike National Forest. The peak, at 9,528 feet (2,904 m) in elevation, is located in El Paso County, Colorado, above Colorado Springs. It is located about 8 miles (13 km) from Colorado Springs along Old Stage and Gold Camp Roads. Old Stage Road is picked up behind The Broadmoor and Gold Camp Road winds through Cheyenne Canyon.

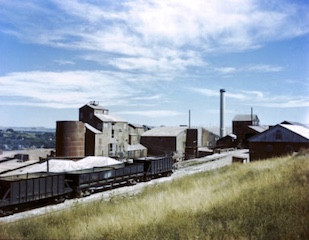

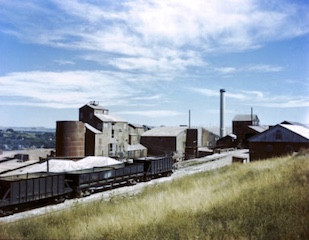

Golden Cycle Mining and Reduction Company was a mining company in Colorado City in El Paso County, Colorado. The company was incorporated in West Virginia and was listed on the Colorado Springs Exchange. Albert E. Carlton was part owner of the Golden Cycle. Directors included Carlton, Spencer Penrose, Richard Roelofs, H. McGarry, L.G. Carlton, Bulkeley Wells.

Cheyenne Mountain is a triple-peaked mountain in El Paso County, Colorado, southwest of downtown Colorado Springs. The mountain serves as a host for military, communications, recreational, and residential functions. The underground operations center for the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) was built during the Cold War to monitor North American airspace for missile launches and Soviet military aircraft. Built deep within granite, it was designed to withstand the impact and fallout from a nuclear bomb. Its function broadened with the end of the Cold War, and then many of its functions were transferred to Peterson Air Force Base in 2006.

Cragmor, first known as Cragmoor, is an area in northeastern Colorado Springs, Colorado, between Templeton Gap and Austin Bluffs. A coal mining site during the 19th century, the area became known as the Cragmor around the turn of the century because the Cragmor Sanitorium was located there. By the 1950s, the mines were abandoned and the land was developed for housing. Cragmor was annexed to the City of Colorado Springs in the early 1960s. The Cragmor Sanatorium became the main hall for the University of Colorado Colorado Springs campus.