The endocrine system is a messenger system in an organism comprising feedback loops of hormones that are released by internal glands directly into the circulatory system and that target and regulate distant organs. In vertebrates, the hypothalamus is the neural control center for all endocrine systems.

The pituitary gland or hypophysis is an endocrine gland in vertebrates. In humans, the pituitary gland is located at the base of the brain, protruding off the bottom of the hypothalamus. The human pituitary gland is oval shaped, about 1 cm in diameter, 0.5–1 gram (0.018–0.035 oz) in weight on average, and about the size of a kidney bean.

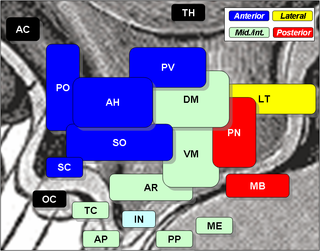

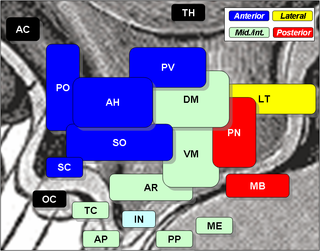

The hypothalamus is a small part of the vertebrate brain that contains a number of nuclei with a variety of functions. One of the most important functions is to link the nervous system to the endocrine system via the pituitary gland. The hypothalamus is located below the thalamus and is part of the limbic system. It forms the basal part of the diencephalon. All vertebrate brains contain a hypothalamus. In humans, it is about the size of an almond.

The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis is a complex set of direct influences and feedback interactions among three components: the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands. These organs and their interactions constitute the HPS axis.

Tropic hormones are hormones that have other endocrine glands as their target. Most tropic hormones are produced and secreted by the anterior pituitary. The hypothalamus secretes tropic hormones that target the anterior pituitary, and the thyroid gland secretes thyroxine, which targets the hypothalamus and therefore can be considered a tropic hormone.

The anterior pituitary is a major organ of the endocrine system. The anterior pituitary is the glandular, anterior lobe that together with the makes up the pituitary gland (hypophysis) which, in humans, is located at the base of the brain, protruding off the bottom of the hypothalamus.

The posterior pituitary is the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland which is part of the endocrine system. The posterior pituitary is not glandular as is the anterior pituitary. Instead, it is largely a collection of axonal projections from the hypothalamus that terminate behind the anterior pituitary, and serve as a site for the secretion of neurohypophysial hormones directly into the blood. The hypothalamic–neurohypophyseal system is composed of the hypothalamus, posterior pituitary, and these axonal projections.

The paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus is a nucleus in the hypothalamus, that lies next to the third ventricle. Many of its neurons project to the posterior pituitary where they secrete oxytocin, and a smaller amount of vasopressin. Other secretions are corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH). CRH and TRH are secreted into the hypophyseal portal system, and target different neurons in the anterior pituitary. Dysfunctions of the PVN can cause hypersomnia in mice. In humans, the dysfunction of the PVN and the other nuclei around it can lead to drowsiness for up to 20 hours per day. The PVN is thought to mediate many diverse functions through different hormones, including osmoregulation, appetite, wakefulness, and the response of the body to stress.

Corticotropic cells, are basophilic cells in the anterior pituitary that produce pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) which undergoes cleavage to adrenocorticotropin (ACTH), β-lipotropin (β-LPH), and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH). These cells are stimulated by corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) and make up 15–20% of the cells in the anterior pituitary. The release of ACTH from the corticotropic cells is controlled by CRH, which is formed in the cell bodies of parvocellular neurosecretory cells within the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and passes to the corticotropes in the anterior pituitary via the hypophyseal portal system. Adrenocorticotropin hormone stimulates the adrenal cortex to release glucocorticoids and plays an important role in the stress response.

Hypopituitarism is the decreased (hypo) secretion of one or more of the eight hormones normally produced by the pituitary gland at the base of the brain. If there is decreased secretion of one specific pituitary hormone, the condition is known as selective hypopituitarism. If there is decreased secretion of most or all pituitary hormones, the term panhypopituitarism is used.

The arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARH), or ARC, is also known as the infundibular nucleus to distinguish it from the arcuate nucleus of the medulla oblongata in the brainstem. The arcuate nucleus is an aggregation of neurons in the mediobasal hypothalamus, adjacent to the third ventricle and the median eminence. The arcuate nucleus includes several important and diverse populations of neurons that help mediate different neuroendocrine and physiological functions, including neuroendocrine neurons, centrally projecting neurons, and astrocytes. The populations of neurons found in the arcuate nucleus are based on the hormones they secrete or interact with and are responsible for hypothalamic function, such as regulating hormones released from the pituitary gland or secreting their own hormones. Neurons in this region are also responsible for integrating information and providing inputs to other nuclei in the hypothalamus or inputs to areas outside this region of the brain. These neurons, generated from the ventral part of the periventricular epithelium during embryonic development, locate dorsally in the hypothalamus, becoming part of the ventromedial hypothalamic region. The function of the arcuate nucleus relies on its diversity of neurons, but its central role is involved in homeostasis. The arcuate nucleus provides many physiological roles involved in feeding, metabolism, fertility, and cardiovascular regulation.

The endocrine system is a network of glands and organs located throughout the body. It is similar to the nervous system in that it plays a vital role in controlling and regulating many of the body's functions. Endocrine glands are ductless glands of the endocrine system that secrete their products, hormones, directly into the blood. The major glands of the endocrine system include the pineal gland, pituitary gland, pancreas, ovaries, testicles, thyroid gland, parathyroid gland, hypothalamus and adrenal glands. The hypothalamus and pituitary glands are neuroendocrine organs.

A neurohormone is any hormone produced and released by neuroendocrine cells into the blood. By definition of being hormones, they are secreted into the circulation for systemic effect, but they can also have a role of neurotransmitter or other roles such as autocrine (self) or paracrine (local) messenger.

Releasing hormones and inhibiting hormones are hormones whose main purpose is to control the release of other hormones, either by stimulating or inhibiting their release. They are also called liberins and statins (respectively), or releasing factors and inhibiting factors. The principal examples are hypothalamic-pituitary hormones that can be classified from several viewpoints: they are hypothalamic hormones, they are hypophysiotropic hormones, and they are tropic hormones.

Neuroendocrinology is the branch of biology which studies the interaction between the nervous system and the endocrine system; i.e. how the brain regulates the hormonal activity in the body. The nervous and endocrine systems often act together in a process called neuroendocrine integration, to regulate the physiological processes of the human body. Neuroendocrinology arose from the recognition that the brain, especially the hypothalamus, controls secretion of pituitary gland hormones, and has subsequently expanded to investigate numerous interconnections of the endocrine and nervous systems.

The hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis refers to the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and gonadal glands as if these individual endocrine glands were a single entity. Because these glands often act in concert, physiologists and endocrinologists find it convenient and descriptive to speak of them as a single system.

The hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid axis is part of the neuroendocrine system responsible for the regulation of metabolism and also responds to stress.

Hypothalamic–pituitary hormones are hormones that are produced by the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Although the organs in which they are produced are relatively small, the effects of these hormones cascade throughout the body. They can be classified as a hypothalamic–pituitary axis of which the adrenal, gonadal, thyroid, somatotropic, and prolactin axes are branches.

Pulsatile secretion is a biochemical phenomenon observed in a wide variety of cell and tissue types, in which chemical products are secreted in a regular temporal pattern. The most common cellular products observed to be released in this manner are intercellular signaling molecules such as hormones or neurotransmitters. Examples of hormones that are secreted pulsatilely include insulin, thyrotropin, TRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and growth hormone (GH). In the nervous system, pulsatility is observed in oscillatory activity from central pattern generators. In the heart, pacemakers are able to work and secrete in a pulsatile manner. A pulsatile secretion pattern is critical to the function of many hormones in order to maintain the delicate homeostatic balance necessary for essential life processes, such as development and reproduction. Variations of the concentration in a certain frequency can be critical to hormone function, as evidenced by the case of GnRH agonists, which cause functional inhibition of the receptor for GnRH due to profound downregulation in response to constant (tonic) stimulation. Pulsatility may function to sensitize target tissues to the hormone of interest and upregulate receptors, leading to improved responses. This heightened response may have served to improve the animal's fitness in its environment and promote its evolutionary retention.

Gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone (GnIH) is a RFamide-related peptide coded by the NPVF gene in mammals.